Motivated reasoning

How it impacts our thoughts and behaviour as collectors on Instagram

Previously, I have written about watch collectors’ addiction to both buying new watches, and social media... and how we could benefit from reducing our dopamine dependence. In this post, although related, I wanted to share some brief thoughts around motivated reasoning and how it impacts our thoughts and behaviour as collectors on Instagram.

Quick definition to start off… Motivated reasoning refers to the cognitive process where individuals engage in selective interpretation or evaluation of information to support pre-existing beliefs, desires, or emotions. In other words, people tend to accept evidence which confirms existing beliefs while rejecting or downplaying evidence which contradicts them. This bias can influence decision-making, problem-solving, and judgement, often leading individuals to maintain their original viewpoints even when presented with compelling evidence to the contrary.

Suppose you walk into a shady neighbourhood and get mugged... if this happens consistently, the part of your brain that generates plans like “walk through shady neighbourhood” would surely to be downgraded in your brain’s decision-making algorithm. Conditioning is what reinforces this learning.

Our hedonic state refers to an individual’s subjective experience of pleasure or happiness derived from certain activities, experiences, or stimuli. In the fields of psychology and neuroscience it is used to describe the positive emotional states that people may encounter in response to various stimuli, such as engaging in enjoyable activities, experiencing sensory pleasures, or achieving desired goals.

Getting mugged is not an ideal experience, so over time you’d see: Plan → higher hedonic state (conditioned on current state) → do plan more (or lower hedonic state → do plan less).

Hold that thought for a moment…

ScrewDownCrown is a reader-supported guide to the world of watch collecting, behavioural psychology, & other first world problems.

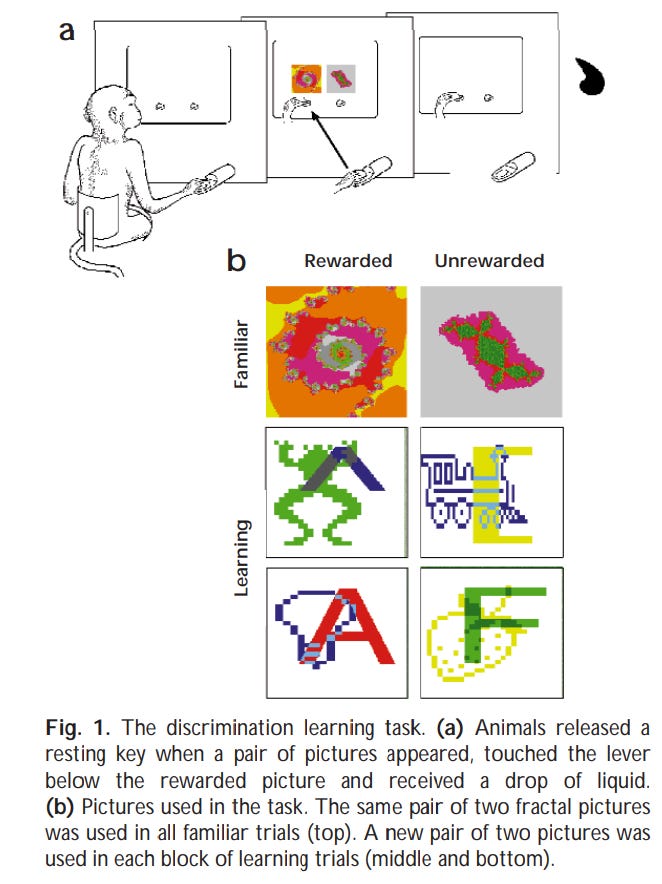

A while back, this guy Wolfram Schultz did some experiments on monkeys, while measuring the activity of dopamine neurons in the midbrain. Schultz found (among other things) three intriguing results:

When he gave the monkeys juice at an unexpected time, they experienced a burst of dopamine.

After Schultz trained the monkeys to expect some juice immediately following a light flash, there was a burst of dopamine at the flash of the light, not at the juice.

When Schultz then flashed the light but omitted the usual dose of juice, there was negative dopamine release (compared to baseline) at the time when juice would have been delivered.