The curse of firm beliefs

Confirmation bias, social affiliations, changing minds, and how this all ties into the watch collecting community

“Rolex is not a real watch connoisseurs brand, it is merely an object used to flaunt wealth.”

“Rolex is the best watch brand to ever exist, with a rich history and a catalogue of classics.”

Which statement is correct?

I’d bet this has happened to you more than once: You’ve spent too long trying to convince someone that their opinion on a topic is wrong; You made rational arguments, you provided ample evidence and you did it all calmly and politely. Despite all that, instead of seeing your point or providing any rational counterarguments, they push back… still convinced of their position being accurate. By the end of your discussion-turned-debate, you are no closer to convincing them of anything, and there are strong odds that your relationship will have taken strain because of this exchange.

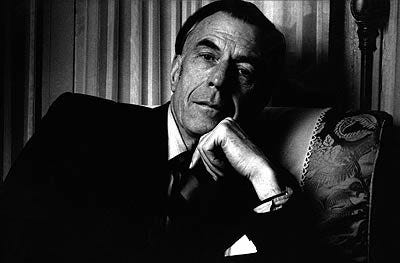

Faced with the choice between changing one’s mind and proving that there is no need to do so, almost everyone opts for the latter.1

John Kenneth Galbraith

Coincidentally, I also stumbled upon an old article with these highly relevant quotes from Leo Tolstoy. Turns out, these statements seemingly led to the coining of a term ‘Tolstoy Syndrome’2 ; fascinatingly, this Wiki Page redirects to the page for ‘confirmation bias’ (which I have discussed before) - and this is probably something you’re deeply familiar with, if you’ve been reading my posts for a while.

ScrewDownCrown is a reader-supported guide to the world of watch collecting, behavioural psychology, & other first world problems. Both free and paid subscriptions are available. If you want to support my growth, the best way is by taking out a paid subscription.

These are Tolstoy’s words (emphasis mine):

“I know that most men, including those at ease with problems of the greatest complexity, can seldom accept the simplest and most obvious truth if it be such as would oblige them to admit the falsity of conclusions which they have proudly taught to others, and which they have woven, thread by thread, into the fabrics of their life.”

“The most difficult subjects can be explained to the most slow-witted man if he has not formed any idea of them already; but the simplest thing cannot be made clear to the most intelligent man if he is firmly persuaded that he knows already, without a shadow of doubt, what is laid before him.”

So what exactly are we observing here, and why? Why are smart people so unwilling or unable to change their minds, even when presented with cold, hard, facts? Why would anyone be minded to hold onto false or inaccurate ideas and beliefs anyway?

Why do we hold false beliefs anyway?

For us to exist on earth, we need a fairly accurate view of the world to ensure we can survive and coexist with other humans. If our view of reality is vastly different from the actual world, we would struggle to live our lives effectively.

If you think about this carefully, it makes a lot of sense. Every person has their own unique “reality”… as the saying goes3:

“We see the world, not as it is, but as we are”

-Anonymous

Now, despite our own unique realities, we tend to have sufficient overlap which ensures we can live harmoniously for the most part. For instance, if you ride a bicycle to work, you don’t actually have complete access to every aspect of reality, but your perception is usually accurate enough to ensure you avoid an accident and arrive safely. Of course, when there is no overlap, things go wrong; the car is supposed to yield, and it doesn’t, because the driver didn’t see you… that’s an accident!

Aside from all this pedantic stuff about truth, accuracy and tangible or verifiable information and objects… humans also seem to have a desire to belong.

In their book The Enigma of Reason cognitive scientists Hugo Mercier and Dan Sperber argue that humans’ biggest advantage over other species is our ability to cooperate. Cooperation is difficult to establish and almost as difficult to sustain. For any individual, freeloading is always the best course of action. Reason developed not to enable us to solve abstract, logical problems or even to help us draw conclusions from unfamiliar data; rather, it developed to resolve the problems posed by living in collaborative groups.

“Reason is an adaptation to the hypersocial niche humans have evolved for themselves”4

If reason is designed to generate sound judgments, then it’s hard to conceive of a more serious human design flaw than confirmation bias. Imagine, Mercier and Sperber suggest, a mouse that thinks the way we do. Such a mouse, “bent on confirming its belief that there are no cats around,” would soon be eaten by a cat! To the extent that confirmation bias leads people to dismiss evidence of new or underappreciated threats - the human equivalent of the cat around the corner - this seems like a trait which should have been left behind as we evolved. The fact that we aren’t extinct, and still possess this trait, proves that it must have some adaptive function (according to Mercier and Sperber). According to them, this trait is is related to our “hypersociability.”

Looking at it from an evolutionary perspective, Mercier and Sperber, suggest this trait persisted to prevent us from getting screwed by the other members of our group. Living in small groups of hunter-gatherers, our ancestors were primarily concerned with their social standing, and with making sure that they weren’t the ones risking their lives on the hunt while others chilled out in the cave. There was little advantage in reasoning clearly, and much to gain from winning arguments.

In his book Atomic Habits, James Clear writes:

“Humans are herd animals. We want to fit in, to bond with others, and to earn the respect and approval of our peers. Such inclinations are essential to our survival. For most of our evolutionary history, our ancestors lived in tribes. Becoming separated from the tribe—or worse, being cast out—was a death sentence.”

Understanding the fundamental truth of any situation is clearly important, but something of equal importance, is simply fitting in. These two desires are in harmony for the most part, but the real fireworks begin when they occasionally come into conflict.

Quite often, as many watch collectors will recall observing, social connection is actually more helpful to our daily lives than bothering to understand the ultimate truth of any fact or idea. The Harvard psychologist Steven Pinker put it this way (emphasis mine):

“People are embraced or condemned according to their beliefs, so one function of the mind may be to hold beliefs that bring the belief-holder the greatest number of allies, protectors, or disciples, rather than beliefs that are most likely to be true.”5

In other words, people often tend to believe things because they make them look good in the eyes of others they care about; NOT because these things are true.

Here’s another fantastic quote from Kevin Simler’s essay on a similar topic which drives the point home:

“If a brain anticipates that it will be rewarded for adopting a particular belief, it’s perfectly happy to do so, and doesn’t much care where the reward comes from — whether it’s pragmatic (better outcomes resulting from better decisions), social (better treatment from one’s peers), or some mix of the two.”6

To connect this back to evolution again - just like animals or our hunter-gatherer ancestors, we are naturally prone to defend our territory. Today, the definition of territory may have changed from a cave or piece of land, to a psychological concept of identity - this forms part of our territory too. You’ve experienced it before; When someone criticises a person’s work, threatens their status or how they see themselves… people instinctively shut down or get defensive! When someone challenges another’s beliefs, they stop listening and go on the attack. This is biological programming, or pure animal instinct.

It is therefore no surprise, holding false beliefs can be useful in a social setting, despite these beliefs not being factual. Just think about how many people attend auctions in Geneva, hang out with people like Aurel Bacs, and enjoy his company… for these people, in that social setting, they are better off believing he’s a lovely man who has no hand in auctions of fake or franken watches or works with an auction house which doctors their photos with malicious intent7. If they do indeed believe he is a criminal masquerading as an auctioneer, then they are forced go against the social grain and shun him publicly, in front of all their collector friends - the mere thought of this probably makes people too uncomfortable, and so, they simply alter their beliefs to turn him into a ‘good guy’.

So what can we take away from this? Well, if you have been paying close attention, you will have realised that if fitting in is the goal, then the key to changing others’ beliefs lies in helping them fit in with a new group who shares the very belief they are afraid of holding! Don’t change minds, change affiliations, so to speak.

Our beliefs are a function of our social affiliations

The previous section concluded: Getting someone to change their beliefs is actually a matter of getting them to change their social affiliation or ‘tribe’. Let’s dig into that idea.

When a person abandons their beliefs (changes their mind), they also risk losing the social ties which are linked with this belief. In the example of Aurel Bacs and his social circle of auction-regulars… if you’ve been attending post-auction dinners for the last 20 years, and suddenly decided to take a stand against Aurel and his alleged criminal behaviour - you can bet your ass there will be no invitation forthcoming for the next annual dinner. This means you’re not only changing your beliefs, but also losing your community and social ties as part of a package deal!

No wonder people are happy to hold false beliefs! Absent any social alternative, without an alternate community to welcome you with your new beliefs… you are always more likely to stick to your old position, no matter what the ‘facts’ suggest.

What this means, is when we want to change people’s minds, we have to become friends with them! In essence we’d welcome them into a new ‘tribe’ of sorts, give them access to our inner circles, and make them realise if they do change their beliefs to align with ours, they won’t be left out in the cold. They will have a replacement home, where the new belief will not seem out of place.

Do you think it was an accident, when Max Busser named his members-only club for people buying his 6-figure watches “The Tribe”? Max is a marketing genius, and this is a phenomenal use of psychology both to create a group of collectors by leaning on the human desire to ‘belong’, and a defensive strategy to prevent widespread negative publicity and have a band of soldiers ready to speak up on behalf of the brand when anyone outside The Tribe has anything negative to say about the brand or its watches. Even people who do have objective but negative views about the brand choose to hold these views more privately than they do for any other brand. That’s because speaking up publicly would constitute an attack against their own tribe… and risk them being kicked out or shunned at the next gathering. If nothing else, it would spur a quiet conversation with Max, where he would urge them to come to him privately, and have a more intimate conversation to give their feedback. Why do they even need to air their negative views publicly when they have direct access to Max? Through this set up, Max has better control over the narrative, and the public perception of the brand benefits from an artificial positive bias outside of The Tribe.

The British philosopher Alain de Botton has a really simple approach to take when you don’t see eye to eye with anyone:

“Sitting down at a table with a group of strangers has the incomparable and odd benefit of making it a little more difficult to hate them with impunity. Prejudice and ethnic strife feed off abstraction. However, the proximity required by a meal – something about handing dishes around, unfurling napkins at the same moment, even asking a stranger to pass the salt – disrupts our ability to cling to the belief that the outsiders who wear unusual clothes and speak in distinctive accents deserve to be sent home or assaulted. For all the large-scale political solutions which have been proposed to salve ethnic conflict, there are few more effective ways to promote tolerance between suspicious neighbours than to force them to eat supper together.”8

Perhaps it is not difference, but distance that breeds tribalism and hostility. As proximity increases, so does understanding.

This Lincoln quote also comes to mind:

“I don’t like that man. I must get to know him better.”

Facts, it seems, won’t change anyone’s mind. Friendship will.

The illusion of explanatory depth

The “illusion of explanatory depth” is the idea that people believe that they know way more than they actually do. In a famous study9, graduate students were asked to rate their understanding of everyday devices like toilets, zippers, cylinder locks and piano keys. They were then asked to write detailed explanations of how the devices worked, and to rate their understanding again. The exercise revealed to the students how ignorant they really were, because their self-assessments dropped.

What allows us to persist in this illusion of exploratory depth, is the presence of other people. In the case of a piano, someone else designed it so that we can play it easily. Humans are very good at this, and we have been relying on each another’s expertise ever since we figured out how to hunt together. We collaborate so well, that we start to lose sight of where our own understanding ends, and others’ understanding begins.

Now, as you will no doubt observe… this blurry line is quite important for our continued survival. Every time we adopt new tools to allow for new ways of living, we also create new realms of ignorance! If everyone had insisted on, say, mastering the architecture of a personal computer, the Information Age wouldn’t have unfolded at the pace it did. When it comes to new technologies, it stands to reason, incomplete understanding is empowering.

That’s all very interesting… but here’s the problem: it is one thing to use a PC without really knowing how it’s built or how it works inside; it is an entirely different thing to favour or oppose, say, an immigration ban or a Brexit vote without knowing exactly what I am talking about!

“As a rule, strong feelings about issues do not emerge from deep understanding.”

Essentially, our dependence on others’ minds reinforces the problem. If your position on, say, the ‘handmadeness’ of a Greubel Forsey Hand Made 1 is baseless and I subsequently rely on it, then my opinion is also baseless. When I talk to another collector and they decide to agree with me, their opinion is also baseless, but now that the three of us concur we feel that much more smug about our views. If we all now dismiss all information which contradicts this ‘belief’ we hold, you get... the modern watch collecting community lol!

This is how a community of ‘knowledge’ can become dangerous. When a person you know, like, and trust believes an idea, no matter how radical it might be… you are more likely to give it serious consideration or merit. You likely became friends because you align on many things in several areas of life - remember the ‘tribe’ discussion above? So given you’re historically aligned, you start to think you should perhaps change your mind on this radical idea too! Conversely, if someone you already hate, who you have never gotten along with, proposes the same radical idea… it is really easy to dismiss them as a clown.

If you imagine each of your beliefs on a scale of 1-10, you’d probably find yourself and all members of your ‘tribe’ cluster around the same level for most individual beliefs. “Hublot is not a relevant brand for serious collectors”, for example, would likely have a huge chunk clustered at 7 or above, on a scale of 1-10! In such a situation, there is no point trying to change the minds of anyone at 1/10 - people at 5 or 6 are more likely to be shifted to one side or the other.

That’s because most heated arguments tend to occur between people on opposite ends of this spectrum, and the most frequent learning occurs from people who are nearby. The closer you are to someone, likelier it is that the one or two beliefs you don’t share will bleed over into each other’s mind. The further away an idea is from your current position, the more likely you are to reject it outright.

Sticking with the spectrum analogy - it is rare for people to simply jump from 1 to 10 or vice versa… the change tends to be gradual, and instead of jumping across the spectrum, we tend to slide along it gradually.

This is also why reading and writing tend to be the most compelling medium to alter our beliefs. The environment is non-confrontational, non-threatening, and allows for people to take time to think about concepts. In conversation, people have to worry about their status and appearance… they must ensure they do not embarrass themselves, and of course, when faced with an audience they will be inclined to double-down on a particular view to avoid looking weak.

Any idea that is sufficiently different from your current worldview will feel threatening. And the best place to ponder a threatening idea is in a non-threatening environment. As a result, books are often a better vehicle for transforming beliefs than conversations or debates.

In conversation, people have to carefully consider their status and appearance. They want to save face and avoid looking stupid. When confronted with an uncomfortable set of facts, the tendency is often to double down on their current position rather than publicly admit to being wrong. Remember the Wei Koh video defending his homage watch launch? That’s a great example!

Public arguments are akin to an attack on a person’s entire identity - Wei Koh told me personally, the word ‘plagiarism’ felt like a slur against his core identity. Conversely, reading about a different point of view is like slipping the seed of an idea into a person’s brain and letting it grow on their own terms.

The persistence of false beliefs

Silence = Death as the saying goes, and the same is true for any belief. Any belief which is never spoken or written down will inevitably die with the person who held it. Beliefs can only be perpetuated or held by others, when they are repeated. As you will now recall from the previous sections, people repeat ideas as a way of signalling they are part of the same social group.

That’s not the only time they repeat them, though! People also repeat beliefs they do not hold - and that is when they complain about them. Before we’re able to criticise any belief, we are forced to reference and repeat it. So we end up repeating the ideas hoping people will forget - but, of course, people can’t forget because we keep talking about it. The more we repeat it, the more likely people are to believe it.10 This is something we’ve discussed before too, and it’s called the mere-exposure effect.

Each time you attack a bad idea, you are feeding the very monster you are trying to destroy. As one Twitter employee wrote:

Your time is better spent championing good ideas than tearing down bad ones. Don’t waste time explaining why bad ideas are bad. You are simply fanning the flame of ignorance and stupidity.

The best thing that can happen to a bad idea is that it is forgotten. The best thing that can happen to a good idea is that it is shared.

So should we just not engage in public discourse?!

Well, that’s not entirely what we’re getting at here. It’s a matter of picking your battles, and being clear about your goal. Why would you choose to criticise beliefs you don’t agree with? Perhaps it might be because you believe the world will be a better place if fewer people held these beliefs?

Well, if that is true, then publicly criticising beliefs you wish to alter, is not really the best approach - that’s what this post is about!

In her TED talk, Julia Galef explains how perspective is everything when it comes to examining your beliefs. She uses an analogy of soldiers and scouts:

People often act like soldiers rather than scouts. Soldiers are on the intellectual attack, looking to defeat the people who differ from them. Victory is the operative emotion. Scouts, meanwhile, are like intellectual explorers, slowly trying to map the terrain with others. Curiosity is the driving force.11

What is clear, therefore, is that to get more people to buy into your beliefs, you’ve got to be more like a scout, and less like a soldier. As Tiago Forte put it:

“Are you willing to not win in order to keep the conversation going?”12

Conclusion

If you think about this whole post and zoom out, it is largely about the sequence of ideas taking hold, leading to beliefs forming, and perpetuating across a sufficient number of people to form what we might describe as “culture”.13

We as watch collectors have seen this in our hobby with all the different subcultures, the most recent phenomenon being independent watchmaking. Rewind about 3-4 years, and people like F.P. Journe and Max Busser were relative nobodies, who struggled to sell their watches to only the most avid horological enthusiasts. As social media allowed these beliefs to spread widely, basic economics kicked in, and the supply and demand equation caused prices to skyrocket. Now, with the crypto bubble and stim checks behind us, and economic woes escalating, prices cooled off - but there’s a new ‘high watermark’. Independent watchmaking culture is here to stay.

What does this all mean? Why did I even write this post? Well, the over arching takeaway is about questioning your own beliefs. We all have hundreds of ‘seeds’ planted in our heads daily. Ideas form, and many die. Others are reinforced periodically, and grow into beliefs we might hold loosely. How many of these beliefs are underpinned by truth, or verifiable facts? Very few.

It is very common for people to mindlessly scroll on Instagram, or through WhatsApp chats with huge numbers of watch collectors… and through this scrolling, folks pick up all sorts of ideas. As they all reinforce this amongst themselves, what started as a throwaway comment becomes a little subculture, and often a divide within social groups. One example is the homage watch debate which ended up with two ‘teams’ - one side was with Horology_Ancienne and being anti-plagiarism, and the other with Wei Koh and being pro-homage. There was a clear winner there, because Wei Koh dug his own grave and leaped into it with his silly video which I shared above) - but you can bet your last dollar that all the people who publicly took sides were noted by many, and this impacts their social status as a collector. Some don’t care, and many will forget eventually - but this is the sort of stuff which would benefit from more intelligent thought by watch collectors.

On face value, Wei and Massena copied a watch, and marketed it for profit. Regardless of the semantics, they have never publicly praised any other homage watch - until they made their own. So what is there to argue about? They know they are just trying to make money, and will spin any story to frame it another way - regardless of what they say, or what you hear - there is a simple story which relies on facts - you just have to take a beat and think about it.

The same goes for anything else. As explained above, you may struggle to get genuine negative feedback about an MB&F, the way you get negative feedback about Omega and Rolex online. That’s not rocket science, so the only solution is to try them on yourself, if you’re seriously considering one. Many people like to talk about Journe’s watches being unreliable and yet, I have had no such experience. That’s just a fact - but I do not doubt that there is no smoke without fire. So I looked into it, and it was true for the older pieces - he has since improved, but there are some older collectors with a long memory, and they do not want to let it go. So do your own research, and survey a bunch of Journe owners yourself to see what they say.

That’s it, really. The summary of this post in one line: challenge your beliefs constantly and have “Strong Opinions, Weakly Held”.14

Finally, let’s not forget we are all watch collectors, and thus, all part of the same Uber-tribe. There may be many subcultures contained within, but the overall goal is to connect with one another, collaborate with them, befriend them, and integrate them where possible into our own sub cultures. The problem which can arise is to get hung up on winning arguments, because we forget about connecting.

The word “kind” originated from the word “kin.”15 So really, if you are being kind to someone, it is the same as "treating them like family. What better way can there be to change someone’s mind, or engage in a mutually beneficial discussion about differing beliefs? Share your views. Develop a friendship. Share a meal. Forward a piece of writing to give them food for thought. 😉

If you enjoyed this post, please do me a favour and hit the heart button below, thanks!

New York Times - Book Review, Came the Revolution… by John Kenneth Galbraith

Bush's Tolstoy Syndrome - The Atlantic

This saying has been used by Anaïs Nin, H. M. Tomlinson, Steven Covey, and others. However, its origin is not known, and it is not possible to provide a precise ascription. (Source)

The Enigma of Reason by Hugo Mercier and Dan Sperber

Language, Cognition, and Human Nature: Selected Articles by Steven Pinker

Crony Beliefs by Kevin Simler

Here’s a few articles to substantiate my claim, in case you are new to the scene:

Phillips Caught Doctoring Engravings With Photoshop – Vintage Rolex and other iconic timepieces under the loupe at Perezcope

‘Tropical’ Speedmaster 2915-1 – A Record-Breaking OmeGaga At Phillips – Vintage Rolex and other iconic timepieces under the loupe at Perezcope

Rolex Daytona 6265 – The “Unicorn” Frankenstein Plot – Vintage Rolex and other iconic timepieces under the loupe at Perezcope

Trash Cartier Crash London At Phillips New York? – Vintage Rolex and other iconic timepieces under the loupe at Perezcope

Religion for Atheists by Alain de Botton

Rozenblit, L. and Keil, F. (2002), The misunderstood limits of folk science: an illusion of explanatory depth. Cognitive Science, 26: 521-562. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15516709cog2605_1

The linguist and philosopher George Lakoff refers to this as activating the frame. “If you negate a frame, you have to activate the frame, because you have to know what you’re negating,” he says. “If you use logic against something, you’re strengthening it.”

“Why you think you’re right — even if you’re wrong” by Julia Galef

The Throughput of Learning by Tiago Forte

I think this phrase comes from Stanford University professor Paul Saffo.

Etymology, origin and meaning of kind by etymonline

Not sure if you're talking about watches or politics, but this fits our current political climate and discourse in the US quite well.

Put me on team Ancienne. Homages are lazy profit grabs.

Finally, this:

This is also why reading and writing tend to be the most compelling medium to alter our beliefs. The environment is non-confrontational, non-threatening, and allows for people to take time to think about concepts. In conversation, people have to worry about their status and appearance… they must ensure they do not embarrass themselves, and of course, when faced with an audience they will be inclined to double-down on a particular view to avoid looking weak.

This is why social media is such a terrible platform for communication. It takes written communication (our most effective and compelling means of communication as you correctly point out) and takes away the thoughtful consideration and reduces it to reactionary bullshit, status seeking, and virtual high fives.

F me.

Great article🫸🫷

We collaborate so well, that we start to lose sight of where our own understanding ends, and others’ understanding begins.

My favourite qoute from this article.

Fantastic read, Well done 👏

Your refrence to Hublot was a fantastic example, I found myself actually liking th fusion classic in blue from an aesthetic point of view, I really think its a good looking watch.

Would i buy it? No, and 9/10 reasons is because the watch community generally hates it and it would make me feel a type of way wearing it. Like a outcast.

Yet I actually like it.

That scenario fits very well to this thread that I thoroughly enjoyed reading.