The French Revolutionary Calendar

A Failed Attempt to Restructure Time

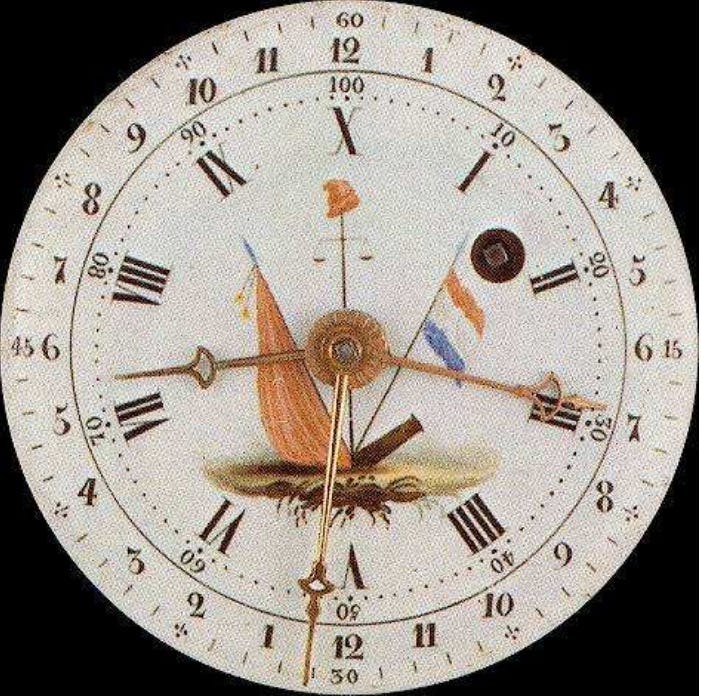

When you look at this pocket watch, what do you notice? Indeed, the dial at the top goes from 1 to 10, instead of 12. This is a story about why this watch exists.

ScrewDownCrown is a reader-supported guide to the world of watch collecting, behavioural psychology, & other first world problems.

After the French Revolution in the late 18th century, the revolutionaries who had overthrown the monarchy and established a new republic were eager to reinvent society. In their zeal for rationality and secularism, they set their sights on a rather ambitious target: time itself.

On October 5, 1793, the Revolutionary Convention adopted the French Republican Calendar, backdating its start to September 22, 1792, the day after the monarchy was abolished and France was declared a republic. This new calendar, based on a system first proposed by Pierre-Sylvain Maréchal in 1788, aimed to sweep away centuries of tradition and superstition and replace them with a scientific, rational approach to marking time.

The calendar was created by a committee of leading scientists and mathematicians of the day, including Charles-Gilbert Romme, a physics professor. It made dramatic changes:

A day now had 10 hours instead of 24.

An hour had 100 minutes instead of 60.

A minute had 100 seconds instead of 60.

The year was divided into 12 months of 30 days each.

Each month was divided into three 10-day “decades” (décades), replacing the 7-day week.

At the end of each year, five extra days (six in leap years) were added as national holidays.

The new year began on the autumn equinox (September 22) instead of January 1

This change was basically a deliberate act of secularisation, meant to reorient the rhythms of French society around the cycles of nature and agriculture rather than the dictates of the Church.

The reformers wanted to disorient people and make them lose track of Sundays, the Christian day of church attendance. Religious holidays and saint’s days were abolished - the calendar aimed to spin society around politics rather than religion. Every day was supposed to be symbolically alike, erasing differences.

Naturally, I suppose in hindsight (!), this made it very difficult to coordinate schedules and commerce with other countries still using the standard Gregorian calendar. The new calendar was extremely unpopular with the French people. Not only was it confusing and alien to their lifelong habits, there was a more obvious and larger gripe: it forced them to work longer before a rest day!

Special clocks had to be made to convert between the new and old systems. The changes were a shocking upheaval in people’s daily lives, imposed from above without their consent.

Now here’s the coolest part - the reason I decided to bother with this post at all…

During the brief period when the French Republican Calendar was in use, a few skilled watchmakers created unique timepieces that displayed both the traditional and the new decimal time systems. These dual-system watches are now super rare, with only a handful of specimens preserved in museums like the Musee Carnavalet in Paris.

The watch I shared at the beginning, housed in the Museum of Applied Arts’ clock collection, is a particularly intricate example. It features a white enamel dial with four subsidiary dials, allowing it to indicate not just the hours but also the days and months in both the old and new formats.

The main dial features two overlapping displays, one with the decimal hours from 1 to 10 and another with the traditional hours from I to XII. Flanking this central arrangement are two smaller dials, one on each side. The left dial shows the days and months using the traditional Gregorian names, while the right dial displays their equivalents in the French Revolutionary Calendar.

Adorning these side dials are two symbolic female figures rendered in enamel. Holding the chain attached to the traditional dial is a weeping woman who represents the Ancien Regime, burdened by the chains of oppression. In contrast, the revolutionary dial is carried by a blue ribbon on the shoulder of a young girl - the iconic Marianne, allegory of the French Revolution. Clad in the tricolor of the French flag and wearing a Phrygian cap, she tramples a crowned, multi-headed beast representing the monarchy and clergy.

Just… fvcking epic!

Powering this remarkable watch is a movement bearing the hallmark of none other than the man himself: Abraham Louis Breguet (1747-1823) - one of the most celebrated horologists, perhaps, ever. Breguet’s workshop, as it happens, was responsible for some of the most innovative and finely crafted timepieces of the late 18th and early 19th centuries.

Watches like this one, with their ingenious fusion of art, politics, and precision engineering, stand as testaments to a turbulent yet creative chapter in French history.

The above table gives an idea of the ‘new vs old’ - but if you’d like to see other clock examples and dig deeper into how decimal time compares with normal time, knock yourself out.

We could end it here, but let’s finish the story and learn how this madness ended.

According to Eviatar Zerubavel, this was part of a broader effort in the age of Enlightenment to radically break with old traditions and institutions and remake society based on reason and science. However, the reformers severely underestimated how deeply entrenched the traditional rhythms of life were. Their attempt to restructure something as fundamental as timekeeping proved to be... naïve I suppose?

The French were not alone in these nutty efforts. After the Russian Revolution in the early 20th century, the Soviet Union under Joseph Stalin also tried to institute a “revolutionary calendar” to abolish the 7-day week and religious holidays. People were assigned staggered rest days based on colours, disrupting families and social groups. Like the French attempt, it faced intense resistance.

Ultimately, these revolutions discarded traditional sources of authority and tried to radically reorganise society based on so called ‘rational principles’ - fanciful stuff indeed. On what basis could the revolutionaries impose new systems after denouncing all that came before as ‘BS’? Pretty insane.

Anyway, the Republican Calendar was finally abolished 1 January 1806 (the day after 10 Nivôse Year XIV) by Napoleon himself, bringing France back in line with the Gregorian standard used by the rest of the Western world.

The calendar is now a weird historical thing that happened, but more than that, I think it is a symbolic warning about the limits of restructuring fundamental aspects of daily life and culture via politics… even if its in the name of ‘reason and progress.’

The Republican Calendar’s short lifespan (a little over twelve years after its introduction) reminds us of something we as watch collectors know too well: Even the most meticulous planning can falter in the face of the all-too-human tension between the lure of a ‘revolutionary and rational future’ and the tenacious pull of the familiar past… just look at all the smaller-diameter watches making a comeback :)

Believe it or not, that “❤️ Like” button is a big deal – it serves as a proxy to new visitors of this publication’s value. If you enjoyed this post, please share it. Thanks for reading!

PS. This post started with a Twitter thread sent to me by a subscriber… thanks J!

It wasn't just the clock and the calendar that they changed. They discarded the Livre (pound) for the new currency of the Franc, changed the linear measurement from Pieds (feet) to metres and the direction of traffic from the left to the right. It truly was a time of Revolution - not the magazine!

👏🏽