Brand power

When names create expectations, and how watch collectors think about brands

Here’s an obvious opening line: What is a brand? Well, Wikipedia states:

A brand is a name, term, design, symbol or any other feature that distinguishes one seller's good or service from those of other sellers.

A short (and incomplete) history on brands and branding

Wikipedia reckons the word, brand, derives from its original and current meaning as a a burning piece of wood; which comes from Old English byrnan, biernan, and brinnan via Middle English as birnan and brond1. Other sources suggest it originates from Ancient Norse, where the word “brandr” means “to burn.” Based on some very incomplete digging, here’s a loose timeline: Around 950 A.D. a “brand” referred to a burning piece of wood. By the 1300s it was used primarily to describe a torch, or, a burning piece of wood used as a light (tool). By the 1500s the meaning had changed to refer to a mark burned on cattle to depict ownership. This is supposedly the start of the term brand that we’re discussing today.

Moo!

Back then, individual livestock farmers would have their own unique mark, mainly to determine ownership when their animals were lost, stolen, or mixed in with animals from another farm or ranch. Each brand mark obviously had to be simple, unique, and easy to identify on a moving target – seemingly a decent set of criteria, even for modern logos.

Just worth noting here, we are talking about the term ‘branding’ being labelled as such - The actual practice of (what we now call) branding is apparently ancient. Some Egyptian tomb paintings at least 4,000 years old depict scenes of roundups and cattle branding, and biblical evidence suggests that Jacob the herdsman branded his stock.

The practice of branding came to the New World with the Spaniards, who brought the first cattle to New Spain. When Hernán Cortés experimented with cattle breeding during the late sixteenth century in the valley of Mexicalzimgo, south of modern Toluca, Mexico, he branded his cattle. His brand, three Latin crosses, may have been the first brand used in the Western Hemisphere2:

The rise of mass media

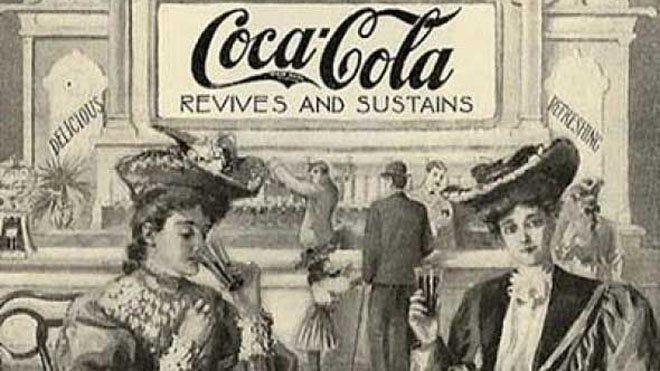

The 1820’s saw the rise of the mass production and shipment of trade goods. As products like booze began to see larger batches and wider distribution, producers began burning their mark into wooden crates or cases of goods to distinguish themselves from competition. Over time, the brand evolved into a symbol of quality rather than ownership; a concept we will of course revisit soon. Products that were perceived as high and consistent quality could command a higher price than their undistinguished alternatives. In 1870, is became possible to register a trademark to prevent competitors from creating confusingly similar products. Brands promised functional benefits such as Coca Cola’s 1905 slogan3, “Coca Cola Revives and Sustains”4. Brands in and of themselves, had become valuable.

The introduction of radio and television gave manufacturers new ways to create demand for their products. In 1928, Edward Bernays (Freud’s nephew), published a book called Propaganda. Bernays argued that by associating products with ideas, masses could be persuaded to change their behaviour. The book was insanely popular, and Madison Avenue took notice. Here’s a couple of old Patek ads from the 1940’s:

By the 1960’s, marketers were using mass media to associate brands with emotional benefits rather than functional ones. Advertisements showed how using a particular brand would make you more desirable, part of an exclusive club, or — as Coca Cola promised in 1979 with “Have a Coke and a Smile!” — just happier!

Enter globalisation

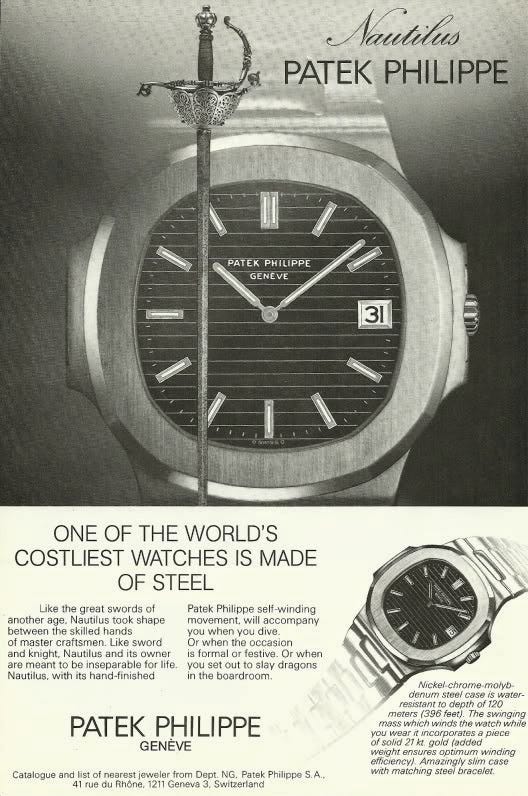

Patek was still advertising products in the 1970’s:

By the 1980’s, distribution channels stretched around the globe, and consumers had more choices than ever. Companies began to focus on building brand recognition for themselves as entities, as opposed to focusing exclusively on their products and services. This allowed them to build loyalty that extended across product lines and gave their consumers a sense of belonging and personal meaning. In 1984, Apple Computer released their iconic “1984” ad which showed users breaking free of rigid conformity by using Apple computers:

The computer itself was almost an afterthought. This concept took off and businesses began to focus on establishing a long term corporate identity rather than creating short ad campaigns. Advertising agencies grew into brand consultancies. Corporate branding extended to non-profits, political groups, and even personal brands for celebrities.

Moving into the 1990’s Jasmina Steele, Patek Philippe Communications Director, joined the company in January of 1996, and one of her first projects was to find a new advertising agency. The story of Patek Philippe's “Generations” campaign changed watch advertising forever, and this article covers it perfectly5.

The first Generations advertisements began running in print in October 1996. The first ads didn’t feature watches at all. They followed the original mission of breaking with product-first advertising, and focused on the customers and the emotions behind the products.

In early 1997, the more iconic tagline was added to the campaign. “You never truly own a Patek Philippe, you merely look after it for the next generation” and this has become so well-known now that it’s almost a cliché, as the above article states.

Below is one of the earliest Generations ads, and a rare “three-generation” one at that; Note the initial “Begin your own tradition” tagline:

What happened next?

The rise of the internet and social media drove the next stage of the evolution of branding for the new genre of corporations. Unlike consumers of the past, internet-connected people were not satisfied with mere consumption– they want wanted participation. Think about social media brands like Instagram, YouTube and TikTok which rely on users to help establish value and perception through likes and engagement. Content sites like Amazon and others on Shopify depend on reviewers to provide their most persuasive content.

Although internet-based companies give up some of the control of their brand image, the loyalty from an actively participating customer base is unparalleled. Viral marketing, search engine optimisation, and outsourced delivery allow organisations to gain visibility and deliver products without spending millions on advertising and infrastructure.

Still, this perhaps worked synergistically insofar as the brands of old, allowing users to ‘rank higher’ through conspicuous consumption of luxury goods and just… expensive things like planes, supercars and watches. If anything, I would argue that the mere ability of people to gain a lot more social status through the virality of social media, meant that any brand capital they spent was worth more.

As an example, in the 1980’s if you bought a Patek Phillipe and wore it, aside from the prestige and other benefits you would gain, you get some sort of social status6 too. This value would only be applicable when you meet in person with others who might recognise the watch, and in doing so, imbue this social value on to you, the wearer. With social media, you can gain status from potentially millions of people online, just by sharing a photo of it.

Closing off this section

Not much of this section is extremely relevant to watch collectors… and get this: none of it is relevant to what I originally had in mind for this post! I kinda just started the post, found it interesting, and went a little deeper than expected (that’s what she said!). This is a relevant insight into why I take long to finish posts… but with that digression and history lesson out of the way, lets move on.

Academic research

I wanted to look into academic research on brands, without making this post too academic - found one as early as 19707 which was only about relating brand attitudes, to the time since you were last exposed to the brand. Not too interesting. Then there was a 1985 paper8 which looks into more useful questions about whether or not to brand, and how branding impacts the positioning of a product in the market. None of this is rocket science.

brand equity… the incremental discounted future cash flows that would result from a product having its brand name in comparison with the proceeds that would accrue if the same product did not have that brand name.