Confessions of a watch modder

On watch modification, authenticity, and the limits of personal taste. When does transforming a watch honour its history, and when does it erase something irreplaceable?

I got this message via WhatsApp a couple of weeks ago: “Ok so let’s assume for a moment you’re a priest and I am in confession with you 🤣.”

No doubt, this was going to be interesting, I thought.

My response was “Go on my son. 😝”

My friend Dee (@limsanity8) had been sitting with a question that had been gnawing at him for a while. He went on to share three watches, each with a different type of modification, each sitting at a different point on what we might (generously) call “creative interpretation” of the original maker’s vision. He was seeking absolution (I jest!), or more seriously, some perspective on what a few watch enthusiasts might call blasphemy. Instead, he got me; which means he got a deep dive into a curious tension that exists in some corners of the watch collecting world.

My immediate response was:

“You can and should do whatever the fvck you want to.”

The more we discussed this, and the more I thought about it, the more complex it became as it unravelled in my head. If watch collecting were actually that simple, we wouldn’t be here having this conversation at all, right?

Estimated reading time: ~24 mins

When Dee framed this as a confession, what he was really asking was something deeper i.e. When does personal expression become disrespect? Or when does ownership give way to stewardship?

Where exactly is “the line?”

The clothing analogy doesn’t quite work

My first instinct was to compare watches to clothing or dress sense. A designer makes clothing with a vision for how it should be worn but really, it’s one’s own taste which determines what you wear and how you wear it. You wouldn’t think twice about tailoring a suit, shortening trousers, or if you’re feeling particularly bold, wearing a tuxedo jacket with jeans.

But then I caught myself… I said, “it’s not build-a-bear.”

There’s gotta be something about watches which makes them different from clothing. Maybe it’s the permanence of this physical object, independent of you, the person. Perhaps it’s the fact that a watch is both functional object and, to some, mechanical art. Or maybe it’s the fact that only so many exist, and we’re all really just temporary custodians of objects which will outlive us. I imagine that if anyone were to take an exceedingly rare watch like a Patek 1518 and then have someone custom-paint Mickey Mouse on the dial because they love Disney, most watch enthusiasts would agree this was completely insane, and unacceptable.

The question Dee was really asking wasn’t whether he could modify his watches. Of course he can, he owns them! The question was whether he should. That question matters because there must be some basic logic behind anyone buying that specific watch in the first place. Some reason why that watch or brand resonated with you enough to buy it over others. The spirit of the maker deserves at least some consideration, even if we’re not entirely sure what that consideration looks like in practice. It is also incumbent upon us enthusiasts to not lose sight of our roles as custodians, to some degree, of these pieces in the context of horological history.

Now, let’s take a closer look at Dee’s watches.

Exhibit A: Atelier de Chronometrie No. 8

This is easily the most extreme of Dee’s modifications; his Atelier de Chronometrie No. 8. This watch is different from the others in one critical way, in that it is almost entirely irreversible.

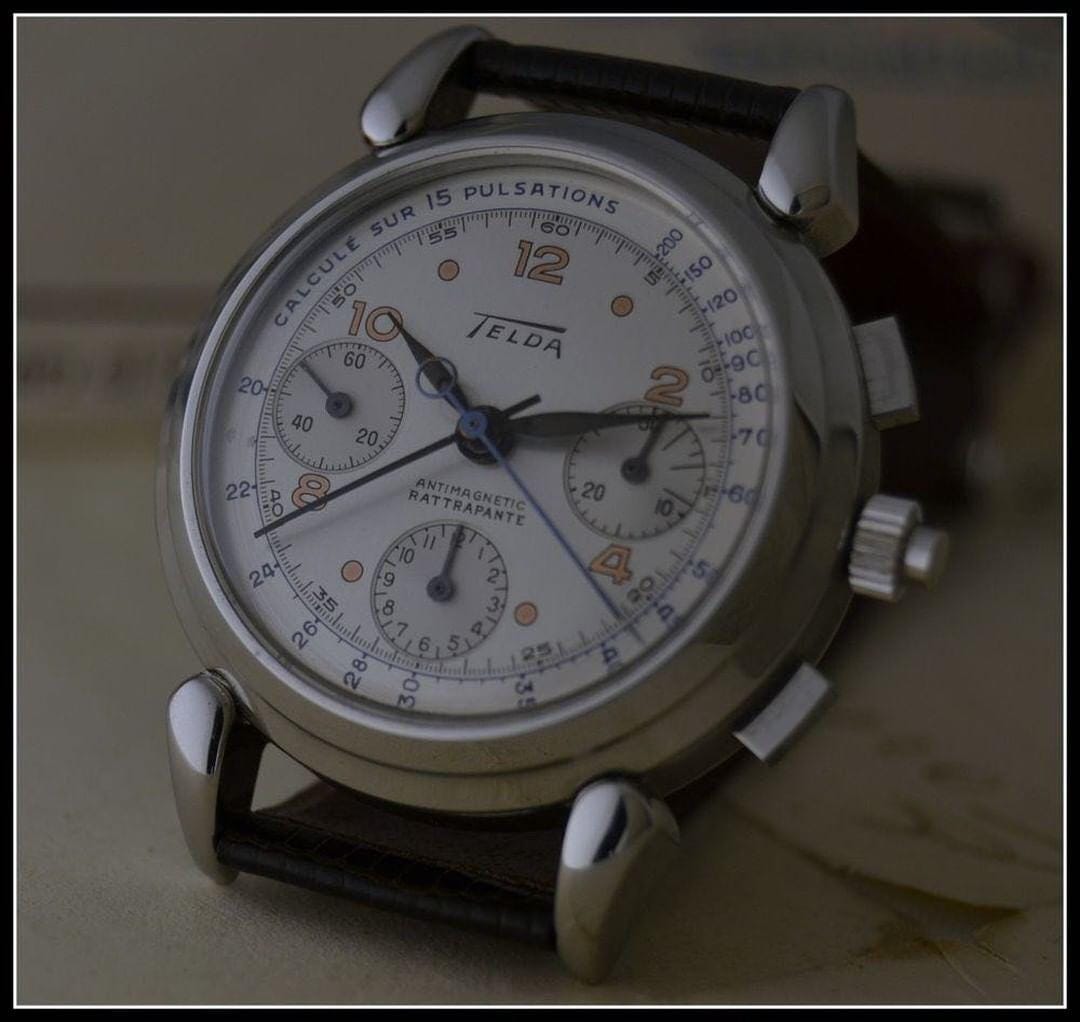

Dee bought this Telda chronograph off eBay for $8,500. The Telda was nothing to write home about; a forgotten brand, with unremarkable aesthetics; this was the sort of thing that sits in dealer inventory for years because nobody wants it. It housed a Venus 185 movement, which is actually rather lovely. Dee then sent the whole thing to Atelier de Chronometrie.

I’m sure you will agree, what came back was quite extraordinary. AdC stripped everything down to the movement, created an entirely new case, dial, hands and even a bracelet. The result is one of the most beautiful watches Dee owns. I actually remember when he first posted it on Instagram; the response was truly overwhelming. People lost their minds; in fact, I would go as far as saying it may have been the single biggest catalyst for AdC’s business trajectory in their entire history.

Regardless, with this watch there’s no going back. The original Telda case is gone, or at least, rendered irrelevant. The dial has been replaced and as far as I understand, this can’t be restored to its original configuration. Dee hasn’t just modified a watch; he has transformed it into something new.

Now, in this case, the modifications are irreversible, but you could argue that the modification feels like preservation instead of vandalism. This same logic could be applied to pocket watch conversions by the way; when the original context is lost, or the brand has been forgotten, you are in some way preserving a slice of history instead of consigning it to the scrap bin.

But let’s sit with that logic for a moment. Is a movement separated from its original case still the same watch? Philosophers call this the Ship of Theseus problem. If you replace every plank in a ship, is it still the same ship? If you take a movement from a pocket watch and put it in a wristwatch case, is it still the same... anything?

Exhibit B: The JLC Reverso Minute Repeater

A 1994 JLC Reverso minute repeater is not exactly vintage in the “pre-war Patek” sense, but it’s still ~30 years old from a major brand. Dee had the dial removed to expose the movement, but everything is reversible i.e. he could put the dial back tomorrow.

The interesting bit is that Dee himself is uncertain about whether he likes it. That hesitation tells me he’s grappling with questions about value, respect, and aesthetics. The discomfort is healthy, as it triggers additional thinking about what modification actually does to a watch.

Should removing a dial feel different from, say, changing a strap? Both are reversible, right? Both alter the watch’s appearance on your wrist. One feels totally acceptable and the other feels... questionable. The only real difference is where you draw the line on what constitutes your definition of “the watch.” We as enthusiasts have collectively decided that strap changes are fine and dial changes aren’t; but really, that’s more of a social construct, and social constructs can be challenged. Here’s the watch in question, post-modification:

Of course, it isn’t lost on me that a dial is rather central to how a watch presents itself to the world. It’s literally the face of the watch. So now the question might be, does the visual interest of seeing the movement justify the loss of the designer’s intended aesthetic? But also, should we care?

Exhibit C: The AP Grand Sonnerie

The third example is an AP Grand Sonnerie with movement work by Stephen Forsey and Giulio Papi. Dee commissioned Josh Shapiro to remove the original dial, create an infinity weave sub-seconds dial, make a floating chapter ring, and craft custom hands and indices. Here it is before he started the work:

I think the result is rather stunning, and again, everything is fully reversible; but is this staying true to what Forsey, Papi and AP themselves intended? Probably not!

Bear in mind, this wasn’t some hack job; Shapiro is known for his guilloche work, and the infinity weave sub-seconds dial is beautiful craftsmanship in its own right. This isn’t some tasteless vandalism so to speak; this one craftsman’s interpretation of other craftsmen’s work.

But does that make it right? Or does that just make it better-executed … but still “wrong?”

Functional justification

Dee added an important detail when we discussed his modifications; they weren’t purely aesthetic. Both the JLC and the AP had an acoustic problem i.e. the chimes were too quiet on the wrist and removing the dials improved the volume significantly. Being able to see the movement while the watch chimes was part of the appeal, for sure, but the primary motivation was in fact functional improvement.

Does this change anything? Maybe. Technical improvements that make a watch more functional tend to feel more justified than outright aesthetic changes. If you’re solving a real usage problem, it could make the modification feel more defensible.

But then if Forsey, Papi, and/or AP had wanted no dial on the watch to maximise the volume, wouldn’t they have designed it that way? By “improving” the acoustics, Dee is implicitly saying the original designers got something wrong. That’s a bold claim to make about masters of their craft, especially coming from a guy who flips burgers at McDonalds1!

Or, it could be that the original designers prioritised aesthetics over acoustic performance, and they assumed owners would primarily use these complications in private settings where low volume actually sounded ‘just right’. Dee has different priorities and uses his watches differently. Is it wrong to optimise for your personal use case?

Reversibility is not a red herring

In my first draft of this essay, I actually argued that reversibility was a red herring. When I first thought about Dee’s modifications, I was inclined to dismiss reversibility as kind of psychological comfort blanket. After all, if you never reverse it, does the theoretical possibility even matter?

My editor later convinced me otherwise… “reversibility isn’t trivial,” he said. “It’s absolutely critical. Preservation of history is sacrosanct.”

Upon further reflection, I decided he was right.

When you modify a watch but keep the original parts, you’re not erasing history at all; you’re merely adding a chapter. The original configuration of the watch is still recoverable. Future owners can reverse your changes if they disagree with your taste. The history of the watch will now include both its original state and your modification.

But when you permanently alter a watch (cutting into a case, refinishing a dial, or completely dismantling the original and creating something new) you are imposing your history on the watch and also erasing part of its own history. You’re making an irreversible choice for yourself, AND for every future owner.

This is why case modifications are particularly problematic; you can’t really restore a case that’s been cut or drilled (even with laser welding and expert restoration, it’s not original anymore). The permanence of change is in fact, the crux of it all.

My editor made an even sharper comparison:

“If you take an original Warhol and modify it, you’re taking a 1/n piece of original art and removing it from the pool of available Warhol works.”

He’s right of course; and it gets better, because whether that modification is celebrated or condemned depends almost entirely on human psychology. If you do it tastefully and the “right people” love it, they’ll celebrate it and everyone else will follow - much like the Superbia Humanitatis, or Singer’s Porsche restomods (we will come to these shortly). If the right crowds don’t love it, it’ll be ostracised as disrespectful vandalism, just like painting Mickey Mouse on a Patek 1518 dial. Regardless of whether people celebrate it or condemn it, you will have permanently removed an original piece from existence, and that is a major point in this discussion.