The Utility of Money: Navigating Wealth, Watches, and Wise Decisions

Exploring the Paradoxes of Value and the Psychology of Watch Collecting in a World of Uncertain Choices

A few months ago I saw a post which described this image as a “foolproof way to get engagement” on social media. That’s probably true, but it also raises some interesting thought experiments, as well as considerations regarding our personal utility of money.

In this post, we will discuss the concept of utility and how it relates to decision-making, particularly in the context of watch collecting and personal wealth. When it comes to decision making, wealth, personal preferences, and the draw of collectible objects all intersect. Using the red/green button choice as a metaphor, we will examine how people navigate the paradoxes of value and the psychology behind their choices… Essentially, trying to make sense of how and why the marginal impact of a single spending decision shifts, depending on one’s circumstances.

Ultimately, the idea here is for you to reflect on your own utility curves and the long-term consequences of your decisions. By understanding the psychological forces at work and the value of a pound or dollar to yourself, you will hopefully make wiser choices which align with your values and minimise future regret.

…people do not make decisions solely based on expected monetary gains, but also take into account factors such as risk aversion, utility, and personal preferences.

Expected value

Consider a random variable X with a finite list x1, ..., xk of possible outcomes, each of which (respectively) has probability p1, ..., pk of occurring. The expectation of X is defined as:

So in this example, the expected value of hitting the green button is $50m and the expected value of hitting the red button is $1m.

If we were all logic-driven robots, we would hit green every time, because 50 > 1. Most people don’t, because the value of every dollar varies from person to person1. For a dropout working 3 jobs, a dollar isn’t merely currency; it’s a crucial step towards their next rent payment. For a recent graduate burdened with student loans, a dollar represents the opportunity to pay off loans and maybe even realise the dream of home ownership.

Conversely, for a retiree with a huge pension and massive savings, perhaps a dollar simply adds to their already comfortable bank balance, and for Warren Buffett, it might as well be monopoly money. It is no surprise, therefore, that people prefer a guaranteed million, because the alternative includes a possibility they will get nothing at all, and this possibility presents as a much greater risk to take.

These ideas are formally encompassed by the concept of utility. Before we get into that, let’s look at an interesting paradox.

St. Petersburg Paradox

The St. Petersburg Paradox is a classic problem in probability theory that challenges traditional notions of decision-making under uncertainty. It was first introduced by Daniel Bernoulli in 1738.

Here’s how the paradox is set up:

Imagine a gambling game where you pay an entrance fee to play. You flip a fair coin repeatedly until it lands on tails. The game pays you $2 raised to the power of the number of flips it took for tails to appear. For example, if tails appears on the first flip, you win $2. If tails appears on the second flip, you win $4. If tails appears on the third flip, you win $8, and so on.

The entrance fee is fixed, say $10, and you can play the game as many times as you like.

The paradox arises when we calculate the expected value of the game. The expected value is calculated, as shown before, by multiplying the probability of each outcome by the payoff for that outcome and summing the results. In the case of the St. Petersburg Paradox, the expected value is actually infinite:

Theoretically, one should be willing to pay any amount of money to play this game. However, in reality, most people would not pay an exorbitant amount to play such a game.

The paradox highlights a discrepancy between expected value, and decision-making behaviour under uncertainty. It suggests that people do not make decisions solely based on expected monetary gains, but also take into account factors such as risk aversion, utility, and personal preferences.

Here are a few examples of how this applies in modern decision theory:

Risk Aversion is the primary point - Individuals may be risk-averse, meaning they are unwilling to pay large amounts for uncertain outcomes, even if the expected value is theoretically infinite.

Behavioural Economics explores how psychological factors influence economic decisions. It suggests that human decision-making is more complex than traditional economic models assume, and things like our perception of risk and loss aversion play significant roles.

Utility Theory seems to go out of the window here - This usually assumes people make decisions based solely on maximising their expected utility. Instead, this paradox shows how people may have diminishing marginal utility when it coms to money… meaning the value of additional money decreases, as wealth increases.

The parallels between the red/green button and the The St. Petersburg Paradox are pretty clear, as they shed light on important aspects of decision-making under uncertainty. Now, let’s dig deeper into this concept of utility.

ScrewDownCrown is a reader-supported guide to the world of watch collecting, behavioural psychology, & other first world problems.

Utility

“Utility” refers to the satisfaction or benefit derived from consuming goods or services. In economics, this concept is measured in “Utils” (the Spanish word for useful), which are abstract units rather than tangible quantities. As a theoretical construct, utility represents relative value and is not a strict quantitative measure of satisfaction. For instance, if investment A has a utility of 100 and investment B has a utility of 150, you would not automatically assert investment B is 50% superior to investment A. Many practitioners also express utility on a scale of 0 to 1.

Utility functions

A utility function is a concept used in economics to represent an individual’s preferences or satisfaction levels with regard to different combinations of goods and services. It assigns a numerical value (utility) to each possible consumption bundle, reflecting the individual’s preferences and level of satisfaction.

…each incremental dollar offers us less utility as we accumulate more dollars.

The calculation of a utility function depends on the specific preferences and circumstances of the individual or consumer. It is typically derived from observation, experimentation, or survey data, where individuals express their preferences through choices or responses to hypothetical scenarios.

Utility functions are used extensively in microeconomic analysis, particularly in consumer theory, decision theory, and welfare economics, to understand and predict individual behaviour in various economic contexts.

There are of course, different types of utility functions… I summarised most of it in this post, but realised it was far too much detail and deleted it all!

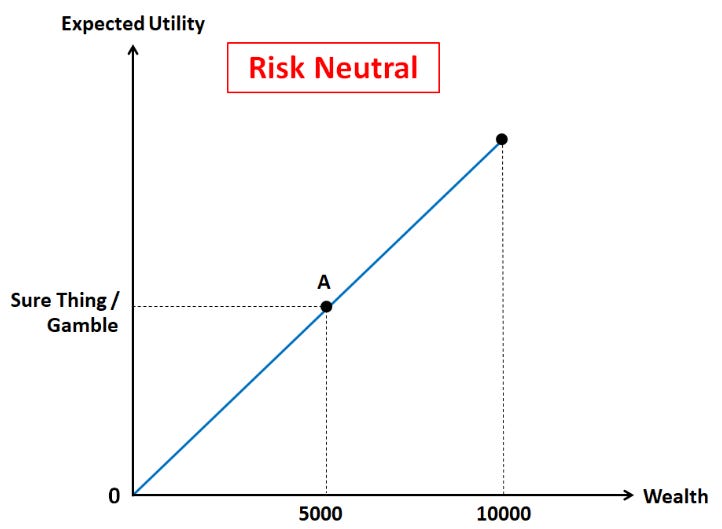

Instead, you can read about it for yourself if you want to, and here are a few more resources for the nerds (link) (link) (link). As opposed to a text summary, here are some simplified graphs to better understand the impact of risk on utility:

These are self-explanatory, I hope! The first shows no regard for risk - Same utility for a gamble and a guarantee. The second shows risk aversion, where you have more utility from a guaranteed outcome, than a gamble. The third is risk seeking, where perhaps the thrill of a gamble, is more appealing than having the money, so the gamble offers more utility. This might sound daft, but oftentimes, this is exactly what is going on when you push the green button! It is also what is happening when you buy a random independent watchmaker with the hope they will ‘blow up’ and your watch will be worth 10x what you paid. This happened a lot in 2021/2022, maybe less of this behaviour is can be observed today.

The final curve shows something interesting, which is we not only experience risk aversion but also, decreasing risk aversion as wealth increases. The blue line is much larger than the red line - As wealth increases, we experience a diminishing utility of wealth, that is, each incremental dollar offers us less utility as we accumulate more dollars.

Intuitively, this makes perfect sense. Warren Buffet wouldn’t care if he dropped $100 on the street, but a single mom working 3 jobs, struggling to pay rent, will definitely feel the pain of dropping $100 on the street.

In the collecting world, we observe this with the most affluent collectors - they have no regard for wealth, so they can buy anything and everything. This makes them seem like exemplary collectors… ‘true patrons of horology.’ While this may be true, it is worth framing their behaviour in this context, before trying to emulate it.

Levels

Clearly then, when faced with the choice between two buttons - a guaranteed million dollars or a mere chance at $50 million - the decision hinges on what those sums mean to you, personally.

Stewart Butterfield, the founder of Slack, was asked on a podcast how his enormous wealth has impacted his life… he responded by saying “beyond a certain level of wealth it doesn’t make your life any better” and went on to list what he considers to be the three levels of wealth:

Level 1. I’m not stressed out about debt: People who no longer have to worry about their credit card debt or student loans.

Level 2. I don’t care what stuff costs in restaurants: How much you spend on a particular meal isn’t impacted by your finances.

Level 3. I don’t care what a vacation costs: People who don’t care how expensive the hotel is or which flight they go on.

This reiterates a key point: When we consider wealth in levels it reveals how certain amounts of money may not significantly enhance one’s life. For instance, an extra $500 might not propel an average person from level 2 to 3, but $50,000 might be enough to shift someone from level 1 to level 2.

Nick Maggiulli quotes Jay-Z2 and uses it as a basis for determining how “0.01% is a good proxy for what constitutes a “trivial amount of money” for any level of wealth.” He then expands on Butterfield’s levels as follows:

Level 1. Paycheck-to-paycheck: You are conscious of every dollar you spend. This includes people with crippling debt.

Level 2. Grocery freedom: How much specific grocery items cost don’t impact your finances.

Level 3. Restaurant freedom: You eat what you want at restaurants regardless of the cost.

Level 4. Travel freedom: You travel when you want, how you want, and stay where you want.

Level 5. House freedom: You can afford your dream home.

Level 6. Philanthropic freedom: You can give away money that has a profound impact on others.

Life circumstances matter as well, and it is therefore not always straightforward to apply absolute values in dollars to everyone; a teenager with a million dollars is not the same as an 80-year old with a million dollars; the teenager arguably has more utility per dollar simply by having (statistically) more years to live, and being healthy enough to be able to do many more activities than the old person.

That said, using 0.01% of net worth as a proxy, Maggiuli provides a helpful list showing the marginal impact of a single spending decision within each level of wealth:

Level 1. Paycheck-to-paycheck: $0-$0.99 per decision (net worth $1,000)

Level 2. Grocery freedom: $1-$9 per decision (net worth $10,000)

Level 3. Restaurant freedom: $10-$99 per decision (net worth $100,000)

Level 4. Travel freedom: $100-$999 per decision (net worth $1,000,000)

Level 5. House freedom: $1,000-$9,999 per decision (net worth $10,000,000)

Level 6. Philanthropic freedom: $10,000+ per decision (net worth $100,000,000)

So basically, if your net worth is $1000, and you’re deciding whether to buy the fresh bakery bread for $5 or the cheap packaged bread for $3 - this $2 difference represents 0.2% of your wealth, and so it is non-trivial. Conversely, if you were worth $10,000, it would probably be a trivial decision (0.02% of your wealth).

I won’t get too hung up on the values here, as this is just a framework to evaluate these issues. You could decide the correct marginal impact value to be 0.05% of your wealth or something else; the key point is this: everyone’s utility curve will be unique, so only you will know the answer which works for yourself.

Kelly criterion

The Kelly Criterion is a mathematical formula used to determine the optimal size of a series of bets or investments to maximise long-term growth. It was developed by John L. Kelly, Jr. in 1956 while working at Bell Labs.3

This was a long section which ended up being too technical, so I moved it to the footnotes.

Watch collecting

First, watch Jeff Bezos explain the Regret Minimisation Framework.

As Bezos puts it:

I knew that when I was 80 I was not going to regret having tried this. I was not going to regret trying to participate in this thing called the Internet that I thought was going to be a really big deal. I knew that if I failed I wouldn’t regret that, but I knew the one thing I might regret is not ever having tried.

Nothing revolutionary, but perhaps a useful exercise to disconnect your mind from the present which is often bound by considerations about utility. With this framework, you add another dimension to your decision making. This will possibly help with watch collecting decisions, but probably a lot more than that, since you will fast forward into the future and assess things from the perspective of your future self.

Consider two examples, one about watches and another without. You have a rare watch which you love, but you don’t use it. You wore it regularly many years ago, but have since expanded your collection and this old piece rarely gets any wrist time. That said, the regular use of this watch coincides with your children being aged 3-8, and many of your holiday photos and your children’s memories reflect this piece as being ‘daddy’s watch.’

Depending on whether you’re sentimental or not, the framing of this story makes it obvious that your future self might never sell this watch. If, instead, you simply saw ‘trapped value in a watch you don’t wear’ every time you looked at this watch… this might cause you to sell it. Low utility perhaps, but high regret potential.

The other example is in our daily life. It could be an opportunity to visit your aging parent(s), or to attend a children’s school play which you know will be boring and pointless… in this instance, again, these appear to be low-utility endeavours, but ones which have high regret potential for your future self.

I would like to wrap up with my initial thought when I saw the red/green button image, describing this thought experiment. I have seen this play out with watch collectors often, and I am sure you have too.

Consider how people ‘default’ to Rolex or Patek as ‘safe bets’ particularly when starting out as collectors. This feels similar to hitting the red button - guaranteed million. They have no real data about other watches beyond what they learned while having a passing interest.

After that, some folks end up going down the rabbit hole of watch collecting, start to appreciate other brands and eventually end up noticing and appreciating other, often independent, watchmakers. As this happens, we start to change our utility curves, and what we ‘gain’ from a watch is very different to what an average non-collector would.

Each watch is more than just a watch. It doesn’t even matter what level of wealth you’re at - the levels can be superimposed onto our utility curve… the only thing which changes is the brands and watches we are interested in. People at level 5 and 6 may be into Greubel Forsey, while those at levels 3-4 may be into Rolex and Patek… but the fact remains, their utility as a collector is not comparable to a non-collector.

In some instances, some newer collectors find themselves taking gambles on unknown brands or watchmakers, and this choice is affected by their level of wealth. They do this because they hope to uncover a future star, but are not at a level which allows them to access a star once they have become a star… they can only have hope if they move early, and ‘get in’ before this ‘star status’ is recognised widely.

Journe is a good example, where you could have bought a brass piece for £40-50k as recently as 2017, and today they are all six-figure watches. The Journe phenomenon is what I believe gave rise to this type of thinking (for this era of collectors - previously might have been Franck Muller etc), and it then trickled down to other brands like early Daniel Roth & Breguet; watches which are all in finite supply.

The more relevant phenomenon is with new watchmakers like Brette, Berkus, Pikulik, Lass, Schaerer and all these other new watchmakers who are having a go at launching themselves… and there are countless ‘level 3 and 4 collectors’ who are genuinely keen collectors, facing the red/green button decision while often lying to themselves about ‘simply appreciating the watch at face value’. Sure, they may like the watches, but there is this ‘phantom utility’ which is affecting their judgement.

Conclusion

Turns out, this red/green button experiment is actually a powerful metaphor for the complex decisions we face as collectors. As each of us traverses different levels of wealth, our perception of value and the satisfaction we derive from each individual watch in our collection will undoubtedly evolve, and our focus may shift from entry-level brands to high-end independent watchmakers… or from Swiss to Japanese watchmakers… Whatever happens, the underlying drive to find satisfaction in our collections remains constant.

Ultimately, the key to making better decisions - the whole point of this blog - lies in understanding our own utility curves and being mindful of the long-term consequences of our choices. As William James so eloquently put it: “The art of being wise is the art of knowing what to overlook.” We each have to find a balance between the allure of the green button’s potential and the comfort of the red button’s certainty.

It isn’t complicated at all. Evaluate a watch on its merits, particularly on characteristics which appeal to you. Don’t speculate on what it might be worth, or how many people are saying “this watchmaker is the next Journe” (or whoever) - you have no way of predicting this, and it will lead to future dissonance.

It is too easy to get enticed by speculators, but depending on your utility curve, this may not be the best use of your funds… especially if you don’t genuinely love the watch.

Believe it or not, that “❤️ Like” button matters – it serves as a proxy to new visitors of this publication’s value. If you enjoyed this post, please let others know. Thanks for reading!

Talking in dollars because the image shows the choice in dollars - On reflection, I should have used pounds, and changed the image - but… too late.

“What’s fifty grand to a mother****er like me? Can you please remind me?” - How trivial was “fifty grand” to Jay Z at the time those lyrics were written (2011)? If we use Jay Z’s estimated net worth of $450 million in 2011, this means that $50,000 represented 0.01% (1 basis point) of his fortune.

For the most part, The Kelly Criterion is used in gambling or investment scenarios where the outcome of each event or investment is uncertain… but has measurable probabilities and payoffs. I thought it was worth including here because the framework seems to lend itself well to the crux of this post. Basically this is a formula which is supposed to help investors and gamblers “manage their capital efficiently” to achieve the highest possible growth while minimising their risk of ruin. I have no doubt you will make the link to watch collecting, just like I did!

The formula for the Kelly Criterion is:

The Kelly Criterion advises wagering a fraction of the “bankroll” (or wealth) equal to the difference between the expected positive return on the bet (in terms of profit per unit wagered) and the expected return if the bet is lost, divided by the odds received on the bet.

A simple example if you want one:

Assume the following:

Mo has $10,000 in his investment account.

The current price of Apple shares is $150 per share.

Mo estimates that there’s a 90% chance that Apple shares will increase in value over the next year and a 10% chance that they will decrease in value.

Mo estimates that if Apple shares increase in value, they will go up by 20%, and if they decrease, they will go down by 10%.

Now, let's apply the Kelly Criterion formula:

p = 0.90 (probability of winning, i.e., Apple shares increasing in value)

q= 1−p = 0.10 (probability of losing, i.e., Apple shares decreasing in value)

b = 0.20 (potential profit per unit wagered if Mo wins)

f∗=(bp−q)/b = ((0.20×0.90)−0.10)/0.20 = (0.18−0.10) / 0.20 = 0.08 / 0.20 = 0.4

The Kelly Criterion result (0.4) suggests an allocation of 40% or $4000 - so he would buy about 26 shares at $150. Clearly, if the downside probability of loss was more than 18%, the answer would be zero - The Kelly Criterion really just defines the optimal bet to maximise return - It assigns no value to risk, other than what is input in terms of the downside probability.

In theory, watch collectors could use Kelly Criterion thinking and apply it to purchase decisions by considering the estimated probabilities of future appreciation or depreciation in the value of a watch and the potential returns, but clearly this is a fool’s errand unless you have a crystal ball to predict these probabilities, not to mention this ignores the qualitative benefits of a watch which usually outweigh the financial benefits. That said, I still thought it was worth mentioning, because of the fundamental basis of the calculation: to think about decisions based on a percentage of your available capital.

This relates to the original point regarding levels; The level you find yourself at, is the basis you must use to make decisions, rather than seeking out collectors who you can emulate.

![{\displaystyle \operatorname {E} [X]=x_{1}p_{1}+x_{2}p_{2}+\cdots +x_{k}p_{k}.} {\displaystyle \operatorname {E} [X]=x_{1}p_{1}+x_{2}p_{2}+\cdots +x_{k}p_{k}.}](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!BfWG!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F2d7589cd-93e6-49e1-8c5c-28c3b3bf1b78_270x23.svg)

Very enjoyable read. My whole fucking box is “high regret potential” - I’m totally fvcked. 😂

That said, press the green button dumbass.

Wonderful post. It has me thinking about the watches purchased vs capital allocation to other areas. At times I have preferred to have the watch and not the investment opportunity. The watch simply meant more than an ROI. This makes me also reflect on Housel’s writings and your write up on his book “The Psychology of Money”. I heard Housel speak about paying off his house. He’s said anyway you slice it, it was a bad financial decision, it doesnt pencil, but paying off his house was the best money decision he and his wife ever made. That stuck with me. The difference in money decisions and financial. I Have reflected on this difference and your post on utility. They seem to communicate a similar sentiment. Sometimes the watch I wanted is worth the decrease in cash. Other times it’s not. Well written article