What Is Good Taste in Watches?

From Bourdieu's cultural capital to "je ne sais quoi"

Back in March last year, I wrote about Pierre Bourdieu’s theory of taste and attempted to apply this to watch collecting. To simplify things, I’d say Bourdieu’s main insight was that taste isn’t personal at all, and that it is a mere reflection of social class and, perhaps, a weapon of distinction. Your preference for a vintage Rolex “Red Sub” over a modern Oysterflex Daytona (despite being similarly priced) isn’t really about aesthetics, but about signalling your position in the cultural hierarchy and distinguishing yourself from those unlike you, or worse, beneath you.

That old post of mine generated minimal discussion in the comments, and in private, some readers also pushed back on the deterministic nature of Bourdieu’s framework. “Surely,” they argued, “there is something more to aesthetic judgement than social positioning?”

I have been sitting on this for, evidently, over a year, and I guess I have come around to the idea that maybe they were onto something. The question of what constitutes good taste, especially in our world of subjectively-chosen wrist candy, is far more complex and annoying than even Bourdieu’s intense analysis might suggest.

So, today, we shall dive a little deeper; we will step beyond the void of the “sociology of distinction” and grapple with a rather philosophical question…

“What is good taste in watches?”

Estimated reading time: ~16 minutes

Democracy Problem

Something that would undoubtedly have made Bourdieu cackle, is that when researchers asked people directly about taste, roughly two-thirds claimed that “one person’s taste is as good as another’s.”1 Let’s call this a “taste democracy”, because it would imply that aesthetic judgement is free to be a personal and subjective thing, on an individual level. If you apply this to watches, it would mean the love for a G-Shock or Seiko 5 would be just as valid as someone else’s obsession with a Patek Celestial.

But does that sound right to you? Well, the same research revealed that even though people publicly embraced this democratic ideal, privately-held views were very different! In private, people maintained hierarchies about what constitutes “good” and “bad” choices. This is the same as how people might diplomatically tell other collectors that their Hublot or Fossil watch collections are “lovely”, but they will probably not be asking the Hublot-collector’s advice when deciding on their own next purchase.

So really, this is a public/private contradiction which says a lot about how the concept of taste actually operates in the real world. Everyone wants to believe that taste is democratic, because this feels fair and inclusive; democracy in taste is very modern and maybe a little woke, but above all else, it’s an egalitarian approach. Yet, everyone also recognises that certain choices demonstrate deeper knowledge, commitment, and understanding than others.

Which means, the question now becomes: how do we navigate this tension without sounding like insufferable snobs?!

Cultural Translation

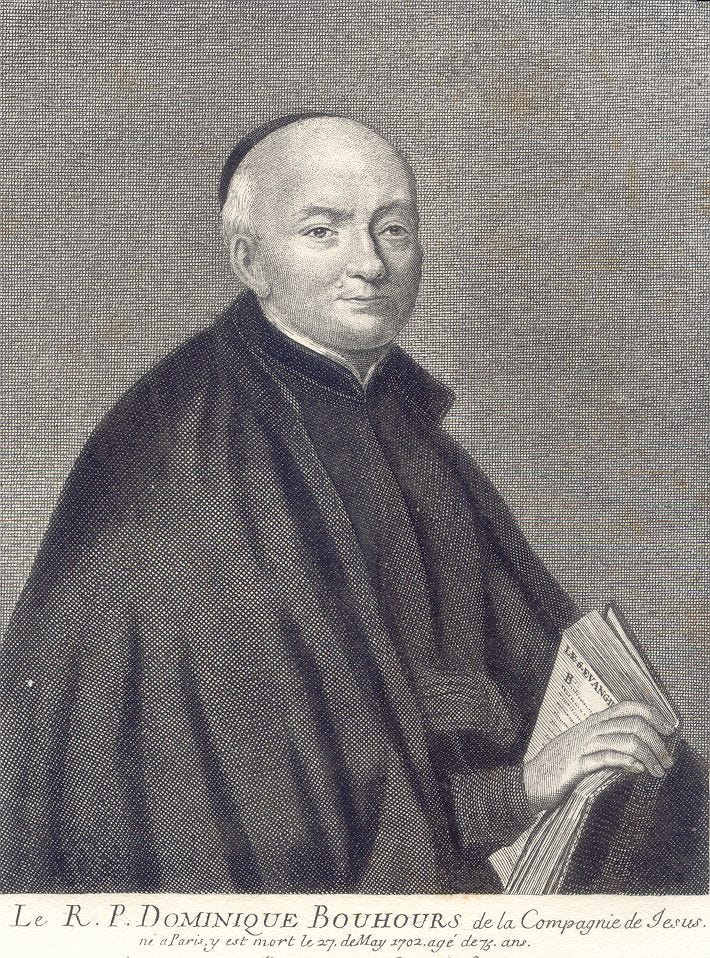

I’d never have guessed it, but Dominique Bouhours was a seventeenth-century French Jesuit priest and grammarian who spent a fair bit of time thinking about taste and cultural judgement. In Bouhours’s view, developing good taste involved learning to “translate” between contexts, audiences, and sensibilities.

Bouhours is perhaps most notable historically for bringing into circulation the notion that matters of taste, chief among them friendship, are motivated by a je ne sais quoi (“I know not what”), something objective yet indefinable in the object of taste (or the potential friend) that pleases the beholder.

We will come back to je ne sais quoi later on, but in this context, good taste requires what we might call cultural fluency. This is an understanding of when classical forms worked, when they needed adaptation, and quite simply, how to make good choices which resonate in different situations.

Applied to watches, this ability to “translate” feels quite relevant, right? The same collector might wear a vintage Royal Oak to a contemporary art gallery opening, but then switch to a vintage Speedmaster for a casual weekend at the track, and then choose a modern Credor Eichi II for a black tie event. The skill isn’t in being able to follow rigid rules, but in reading the room, and understanding which piece appropriately communicates what you want it to, while also staying true to your own aesthetic convictions.

This framework would explain why certain collectors seem effortlessly tasteful in many different contexts. It would appear that they do not fit with Bourdieu’s class-based templates, nor are they ticking boxes on a list of “approved” brands. Instead, they appear to have developed the ability to adapt their choices and even while doing so, they maintain a coherent personal aesthetic. On a more general basis, this is the equivalent of being able to quote Dostoevsky at dinner, discuss football in the pub, debate Star Wars trivia among friends, and do it all without ever seeming pretentious or false.

New Snobbery

In my previous post, I wrote:

A tastemaker is only as good as their ability to predict the next big thing, but in some ways, if they are influential enough they can create the next big thing by simply wearing or using it. John Mayer is a good example, in that he became known as a tastemaker when he first appeared on Hodinkee in 2013, because he seemed to be ahead of the curve in ‘picking winners’ and then, by the time he came back for round two on Hodinkee in 2019, whatever he said, seemed to drive tastes for those who identified with him from the first video.

Recent research on contemporary cultural elites reveals that this kind of taste-making has evolved into something far more sophisticated than traditional snobbery.2