The Guilloché Deception

A Watch Critic's Perspective: From Atelier Wen to industry giants, discover how marketing hype and industrial shortcuts are eroding a cherished watchmaking art.

Today’s post was created by A Watch Critic. I have teased this post for a few weeks already, and it’s finally here. Today our guest writer reveals the reality behind many modern guilloché dials; Which is that the reality of their creation is often quite far removed from the romanticised narratives peddled by watch brands and perhaps more so, the media outlets selling them.

This piece delves into the questionable practices of companies like Atelier Wen and Revolution, whose recent collaboration raised eyebrows with dubious claims about their production methods and timelines.

From the proliferation of CNC-machined dials masquerading as handcrafted artistry to the homogenisation of designs from major suppliers, this critical examination challenges the industry’s integrity and calls for greater transparency in an era where ‘true’ craftsmanship is increasingly rare.

Guilloché Dials: A Watch Critic's Perspective

Guilloché dials are often highly regarded in the watch community among the different dial types available. Up there with enamel and stone dials, these have traditionally been reserved for some of the most exclusive and desirable watches. These dials are celebrated for their tradition, intricate patterns, and the painstaking craftsmanship they all represent.

However, the reality of how these dials are often produced today diverges significantly from the romanticised narratives perpetuated by some brands, and more accessible versions of guilloché dials have shown up recently.

As someone who calls himself A Watch Critic, I feel it is my responsibility to peel back some of the marketing hype surrounding guilloché today, and scrutinise the true nature of these supposedly artisanal creations a little beyond their initial appearance or what many watch blogs, sponsored or otherwise involved with brands, would have you believe.

The term Guilloché covers a wide spectrum of finishes that all appear similar but can have vastly different costs associated with creating them. There are 7 types you should be aware of - in order of typical complexity and cost to manufacture:

Straight Line Engine Guilloché - Similar to the Rose Engine however scribing straight lines only, may include patterns and involves significant manual adjustment. This requires a high degree of skill. Often used to finish edges, borders or used for certain straight patterns such as a basket-weave. Which can become very complex and more expensive than a Rose engine pattern, in the case of for Example Josh Shapiro´s Infinity Basket-weave pattern which is extremely time consuming to produce.

Rose Engine Lathe Guilloché - The Rose Engine tool creates circular patterns based on brass “rosettes” in a very traditional and manually operated way, often these are antique machines and require a very skilled operator.

CNC Scribed Guilloché - This CNC approach tries to replicate a traditional Guilloché engine by making a tool tip actually cut the dial like a guilloché engine would as it´s moving the tool rather than the dial. This approach is much faster and results in a very consistent clean cut.

Laser Engraved - The precision of a laser allows complex and perfectly executed dials, but requires very specialised equipment and The finish can look a bit too sterile, similar to milled CNC. Cost will depend on the type of laser used and depth and quality of the finish.

CNC Milled Guilloché - Milling is fast and creates a very clean finish, but lacks the character of traditional guilloché dial as it´s using a rotating spindle and different cutting tools to achieve the desired effect, rather than a real cutting motion. This is even more uniform and faster to produce.

Pantograph Guilloché - this could be considered a type of guilloché as well, but does not require the skilled hands of a Guillocheur, instead the Pantograph follows a set design and automatically guides the cutting tool. Most famously applied to create the Royal Oak dials.

Stamped Guilloché dials - The bottom of the barrel when it comes to guilloché, but even here there are many different qualities of stamping, from very cheap shallow stamping you might find on a 200 dollar watch to quality deep and precise stamping used by Patek and AP on several models that are sometimes even moulded from a real pattern created by a master guillocheur.

I will skip the history and further explanations as there are many great articles and books available that have covered this extensively. I enjoyed this recent Monochrome article on the topic which also features very nice examples. The same article highlights a couple of important points:

“Yann Von Kaenel from Décor Guilloché SA (an atelier specialising in guillochage based in the Neuchatel area) explained to us, “It’s not the machine that does the work, but the hand of the person operating it.””

“The precision of the piece’s positioning, the rotation speed, and the pressure applied to the tool for each line are crucial for achieving a uniform and consistent decoration. Guillochage is both time-intensive and unforgiving; hours of meticulous work can be compromised in an instant. The most intricate dials may necessitate a full day of labour, sometimes incorporating over 1,000 distinct cuts.”

Atelier Wen and the Reality Behind the 36-Hour Dial - “Perception” or Deception?

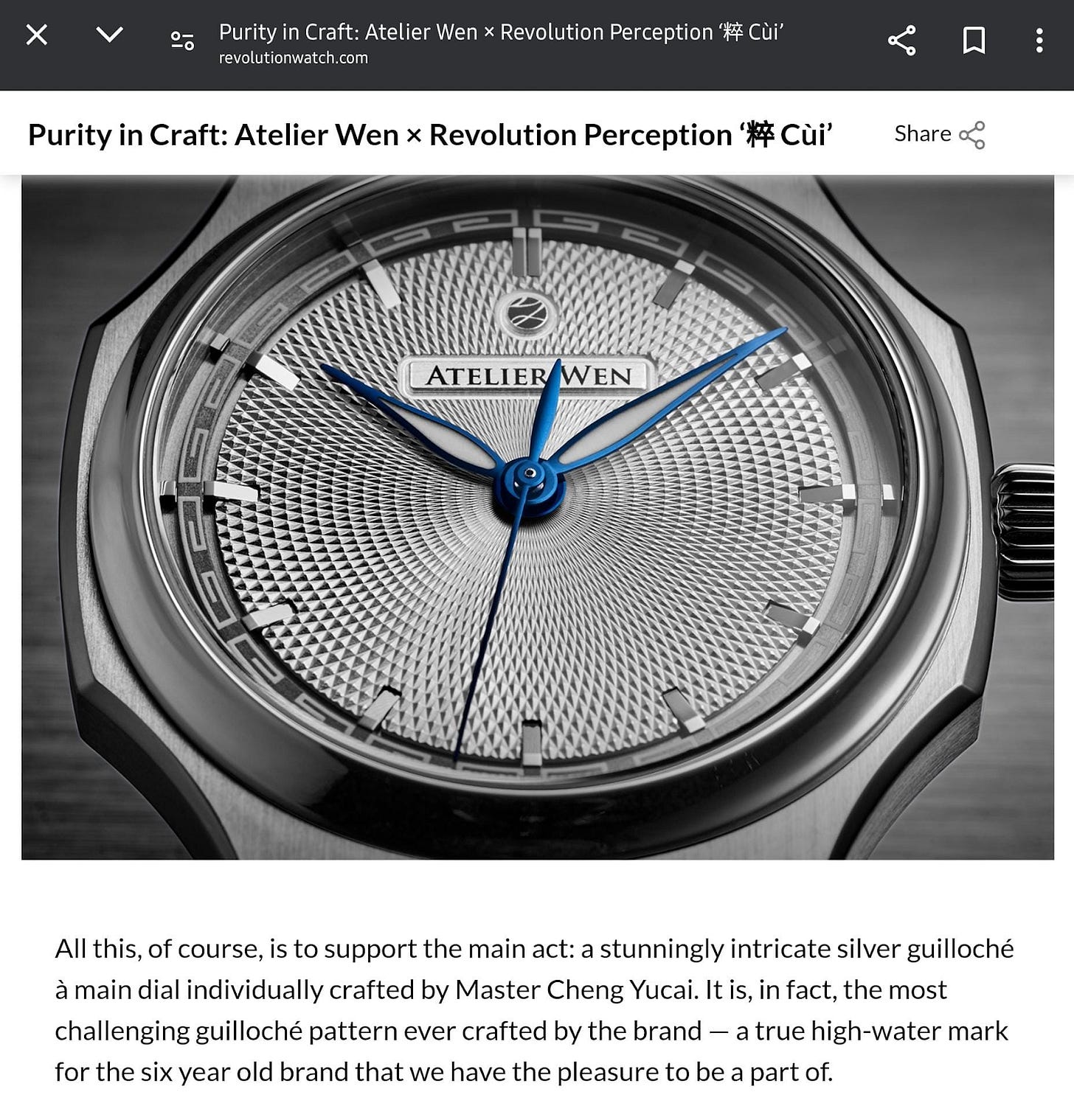

As a case study to make my point, I want to explore a very recent case of an affordable Guilloché dial offered by Atelier Wen in their recent collaboration with Revolution Watches.

But first, some background. The French founders of Atelier Wen - Robin Tallendier and Wilfried Buiron - come from backgrounds in investment banking and private equity. They collaborated with “Master Cheng,” a respected watch dial maker, to combine skilled craftsmanship with affordable Chinese manufacturing, creating a brand that emphasises both quality and Chinese origins. While some might interpret their approach as more business-driven, others see it as a strategy to introduce quality Chinese watchmaking to a broader market.

The design of Atelier Wen’s watches has drawn frequent comparisons to models like the Vacheron Constantin 222 and Patek Nautilus, appealing to the trend of steel sports watches. However, the brand has managed to stand out, particularly with its handmade guilloché dials and emphasis on its Chinese heritage. The guilloché dial, in particular, has been praised for its attractiveness, especially given the price point, and has helped the brand quickly establish a loyal following.

Anyway, the Revolution Perception ‘粹 Cùi’ was the source of considerable debate on Instagram as well as several watch-chat groups.

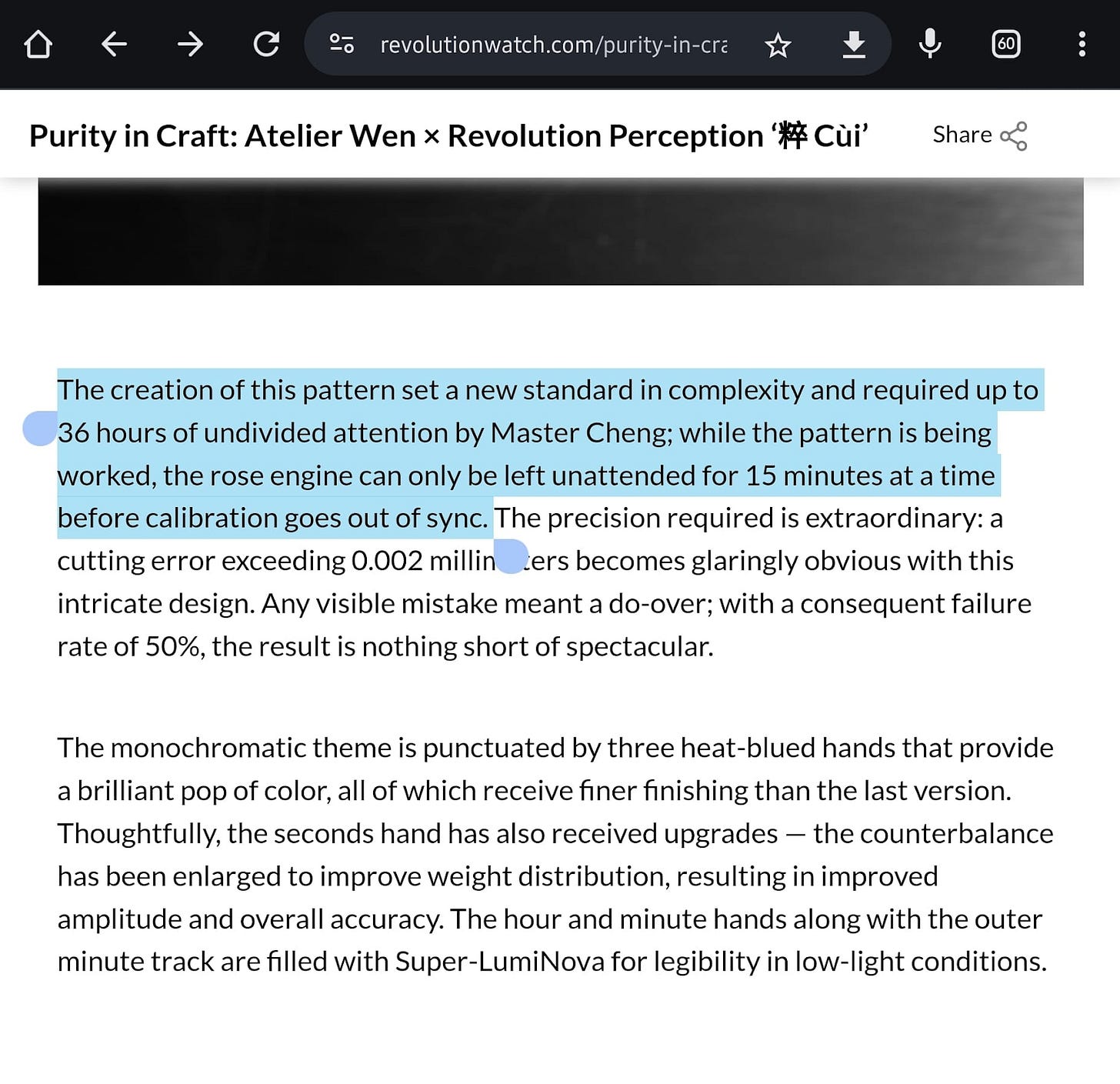

The dial was reported to take 36 hours to complete, which surprised many familiar with guilloché - Masters like Josh Shapiro put this claim into doubt by stating this could be done much faster on a typical rose engine. As mentioned in the Monochrome article a very complex dial can take an entire day to create. The diamond pattern on the Atelier Wen however is actually a very straightforward design in the world of guilloché and without, for example, any changes in the pattern or complex subdials to work around.

Initial claims by Revolution mentioned that Master Cheng himself created the dial for the new Revolution Perception, using a traditional rose engine lathe. Below are some screenshots from the Revolution website, clearly mentioning a Rose Engine as well as Master Cheng being the one creating these dials by himself:

These claims conjure images of an artisan meticulously crafting each pattern with the highest degree of skill, a notion that appeals deeply to enthusiasts who appreciate traditional watchmaking - by hand. While a CNC machine could achieve the same result in around 30 minutes, it is the skill and experience of the watchmaker or artisan that adds tremendous value and charm, of course.

However, a recent video released featuring both the founders of Atelier Wen and Revolution revealed a somewhat different reality than was originally painted;

It turns out, three apprentices are actually required, operating the guilloché tool in a kind of Olympic relay session back-to-back for 12 hour (!) 8-8 shifts. They added, that this is alongside Master Cheng, but his exact role is not made clear. Apparently the tool used will lose it’s setting after ~15 minutes, which necessitates this approach.

Other videos on Atelier Wen’s YouTube channel show 3 apprentices also creating the traditional rose engine dials for their regular Perception models, so is it more likely Cheng is now simply charge of overseeing them (and perhaps quality control) rather than spending much time behind the lathes himself?

Yet, there are still several mentions on both AW’s website and Revolution, of “China’s sole guilloché master craftsman.” This directly contradicts the reality of apprentices rather than “Guilloché Masters” (since there is only one) making the dials.

One thing is clear, these dials are not solely made by Master Cheng himself, if at all.

After some criticism of the communication on their website, terms such as “the workshop” or “the atelier of Master Cheng” are now being used to clarify he is not making these dials by himself and he has become more a brand name like “Voutilainen” (who, of course, also doesn’t create the dials himself either).

Kari’s dials are instead made by his atelier of “guillocheuses” ladies that are each highly respected masters of their craft. Through Kari’s dial business Comblemine, he also offers their services. As a much cheaper alternative, CNC options in many of the same patterns are available as well. While the name Comblemine and Voutilainen usually conjure up thoughts of hand made dials, that is clearly not always the case.

The state of the industry today means that if they don’t shout about their dials being hand made you can almost be sure they are not.

I am sure most of the apprentices at Cheng’s Atelier have some solid experience by now, as they have been around for 5+ years between them, which is actually about how long it typically takes to begin to master the art of Guilloché. So are they early-stage masters in their own right, or even close to the guillocheuses at Voutilainen?

On a related side-note I found in my research that Cheng’s guilloché atelier existed before Atelier Wen was even founded, under the name Guillocheng.

Guillocheng is actually a subcontractor to Atelier Wen, and he produced watches/dials that show a more than striking resemblance to the current Atelier Wen watches in terms of dial layout and design:

The story of how “Guillocheur Master Cheng” honed his skills as an autodidact and built his own rose engine lathe is of course admirable, and something many enthusiasts would happily buy into. Atelier Wen is also undoubtedly helping support Chinese watchmaking, which is currently showing a lot of exciting things with several brands and master watchmakers popping up.

Qin Gan is one of the most impressive independent watchmakers from China today for me, using a lot of traditional “haute horlogerie” hand made watchmaking techniques to build these watches to an incredibly high finishing standard. Innovative brands such as Behrens on the other hand are also making some big waves with an almost diametrically opposing approach; leveraging machine made manufacturing and instead focusing on innovations like unique complications and ultra light design.

One major gripe I have with Revolution, and to a lesser extent, Atelier Wen (as they are equally responsible for their communications), is that the corrections made both on the Ateliers Wen and Revolution websites, about who actually created these dials, were made only after the watch was completely sold out already! This could be considered too-little-too late as the false-advertising or “deception” (objectively speaking) had already convinced and possibly misled enough collectors by then.

However, the more I learned about this dial, the more it became apparent where the shortcuts are being taken to achieve what at first glance looks like incredible value for a true traditional guilloché dial made by the “sole Master Guillocheur in China.”

Delving a little more into how Cheng’s Rose Engines are actually designed, I noticed a key difference between the design that Cheng and his apprentices use and a traditional Rose Engine; how the actual cutting is happening.

Cheng seems to use an elaborate addition to the otherwise traditional looking rose engine. This extra part closest to the operator allows precise adjustment of the pressure using series of wheels and fine screwed adjustment mechanisms and gauges to help adjust and monitor these settings to the micron level:

Now contrast this with a traditional Rose Engine that a “true” Guilloché Master like Jochen Benzinger - one of the few remaining in Europe - would use, and how most Rose Engine Lathes I have seen typically work.

A key part is the “slide” or “carriage” where his right thumb is resting on, which applies the actual cutting pressure. This requires great experience and skill to do consistently and smoothly while also rotating the dial at a steady pace and releasing in time to not overshoot or require any extra cuts or corrections.

Josh Shapiro also mentioned in several interviews and talks he has given at the Horological Society of NY how much time it took him to master this kind of control and feeling for the machine. As well as manufacture and maintain parts like the pattern bars and cutting tip himself.

Master Cheng seems obsessed with high precision, which could be one reason he is choosing this much more controlled approach rather than the more manual artisanal approach.

Another reason could be a desire to simplify this technique to ensure even less skilled operators can do the work. Since it can take 10 years to truly master the art of guilloché, scaling up production is typically a big challenge.

Evidently, after just 5 years his apprentices have been already making production dials, possibly for years already. That is in itself commendable if the results are as good as that of a master, but that is where the Atelier Wen dials, on closer inspection, don’t seem to stack up.

While precise in terms of tolerances, the lack of fine manual control to control the cut, results in a fairly rough appearance compared to something produced by traditional artisanal independents like Benzinger and Shapiro. Examples from Breguet and Patek have an even smoother finish, but this may be partly due to finishing steps that are applied to those such as some subtle medium blasting to remove machining marks.

That said- at this price - it is of course more than fair to assume there are quality differences like these. The issue I have is with the suggestion that people are receiving a guilloché piece from a Master Guillocheur, made on a traditional Rose Engine - this comes with a certain expectation of quality and refinement but most importantly, a human touch.

Perhaps counter intuitively, 100% perfection is not so desirable in Guilloché dials; many collectors appreciate being able to see the human touch and subtle variations in these dials. After all, a perfect result can be obtained consistently from CNC today and can come across as too sterile. So why would you want something that looks like it is made by machine?

It’s the Japanese concept of Wabi Sabi that comes to mind, embracing imperfections as a sign of craftsmanship and human touch. Which is what gives traditional guilloché much of its value and more importantly, charm.

Besides the cutting approach, the cutting tip used also has a significant impact on the finish. Traditionally a polished steel cutting tip is used which the dial maker mirror polishes regularly to ensure the smoothest cut. Cheng uses a Diamond tip cutter instead, which is modern development, delivered precut, and will keep sharp for much longer. This requires far less work to maintain, but at a cost of the quality and aesthetic appeal of the cut itself.

Pictures by Beans and Bezels, from their great article on guilloche.

On the more affordable end, a true rose engine guilloché from a master like Benzinger, can be purchased for less than €6,000. Take, for example, this chronograph from Staudt which is exactly what Jochen is working on in the linked video:

The real revelation however came later, that Atelier Wen’s newest Revolution dial was, interestingly, not produced using a Rose Engine lathe at all, but instead using a type of manual scribing tool I assume they built or modified for the purpose. A method which, while requiring some manual adjustment, does not demand anywhere near the nuanced hand pressure and skill associated with a rose engine lathe; It is instead operated by turning knobs while checking gauges to ensure the right setting depth is selected.

This essentially functions like a manually controlled CNC machine, but instead of a computer making hundreds to thousands of super accurate small adjustments over multiple cuts per line, it is all done manually. One of my childhood heroes, MacGyver, would be proud of Cheng rigging up this manual CNC from parts he gathered or machined himself!

The approach simply works line-by-line rather than following any pattern as a Rose or Straight Line lathe does. All these manual adjustments could explain the 36 hours taken, to a large extent! It requires a lot of concentration of course, and clearly, a lot of time to operate.

The skill barrier is likely significantly lowered as it does not require the years of experience it takes to master the manual cutting slide, and it breaks the process into many simple steps that can consistently be followed. Master Cheng can train a larger number of guillocheurs more quickly, thus potentially increasing production capacity in future.

This approach allows for more standardised training, where workers can be taught to operate the lathe with the preset parameters, focusing on consistency and efficiency rather than the nuances of manual pressure application one would expect with a traditional rose engine.

The error rate is apparently still high (probably also because they work with 3 different operators on a single dial!), exhaustion from 8 hour shifts must be a contributing factor too.

However, given that master guillocheurs can typically create complex multiple-pattern dials in 8 hours, let alone 36 hours, I am not sure if we should be so impressed by these results or place any value in the long duration it takes to achieve them. It is proudly shared as a selling point nonetheless. Do you think time spent, on it’s own, is a valid selling point?

Since this technique closely resembles the operation of a CNC machine, minus the digital precision and speed of Computer guidance, let’s look at how it compares with CNC. After consulting with some experts, my understanding is that a CNC machine could likely complete a simple diamond pattern like this in less than 30 minutes, including setup!

Considering the results will effectively be identical or likely slightly worse due to chances of human error, what is the appeal exactly? The operation simply taking a lot of time, is not something which appeals to me personally, and tends to indicate inefficiency more than artisanal craft. Especially given the traditional alternative is so much quicker, and of superior quality. This is likely why this 36 hour statement drew so much criticism and even ridicule from the watch community as well as professional guillocheurs.

I will end this section with a quote from the late great master George Daniels. In his book, Watchmaking, he noted:

“A constant pressure on the slide is by far the most difficult skill to acquire in engine-turning and upon it depends the whole visual quality of the work.”

George Daniels

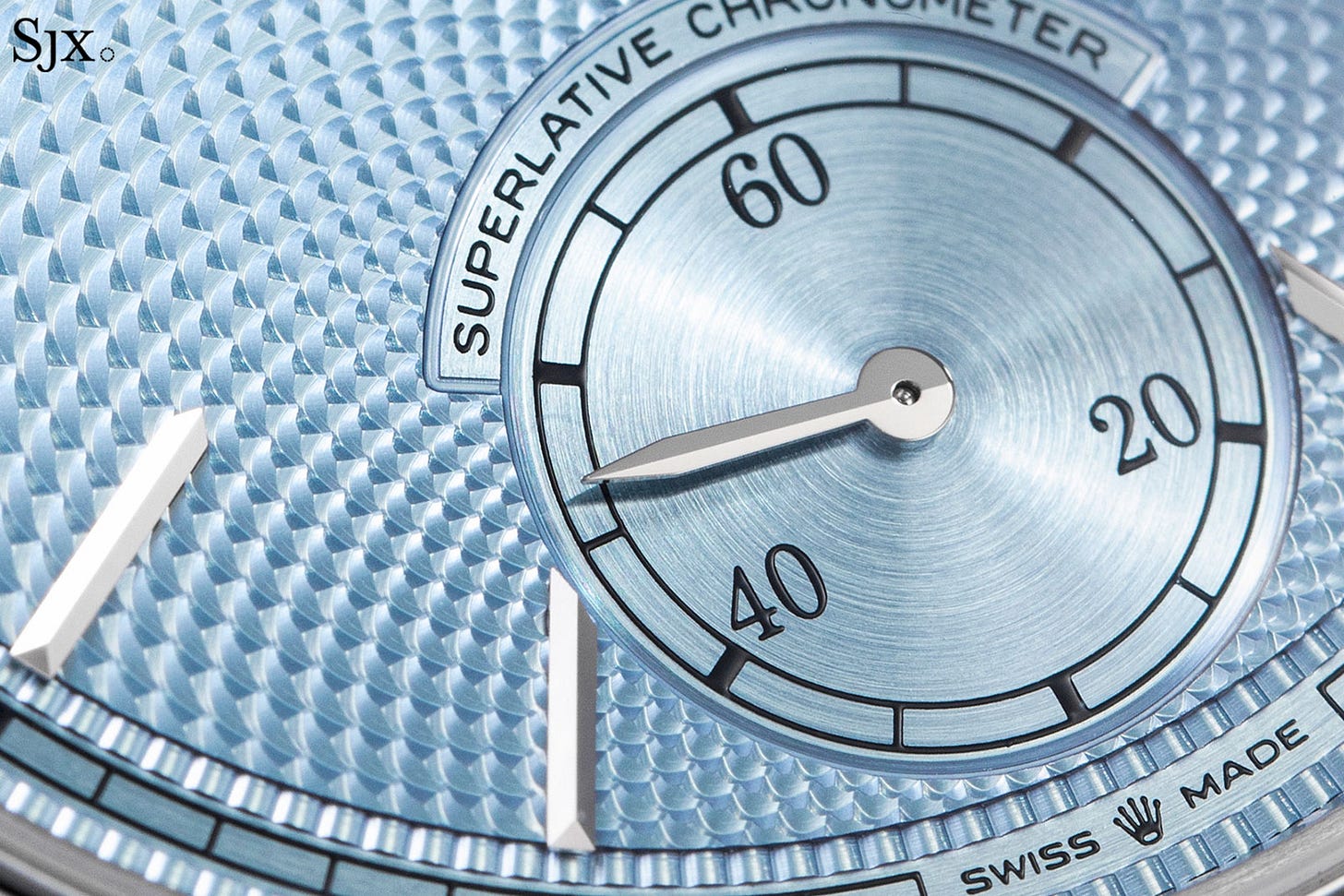

Rolex and the Rumour of CNC-Made Guilloché

Before being accused of only picking on the little guys, let’s direct some scrutiny on industry titan Rolex, which recently had its own re-entry into guilloché. They have produced guilloche dials before, and most well-known may be the straight-line “tapestry” guilloché we see on Day Dates. But many rarer patterns have been created too:

Luxury Bazaar has a guide on Rolex dials, which includes many Day Dates and Cellini models with guilloché dials

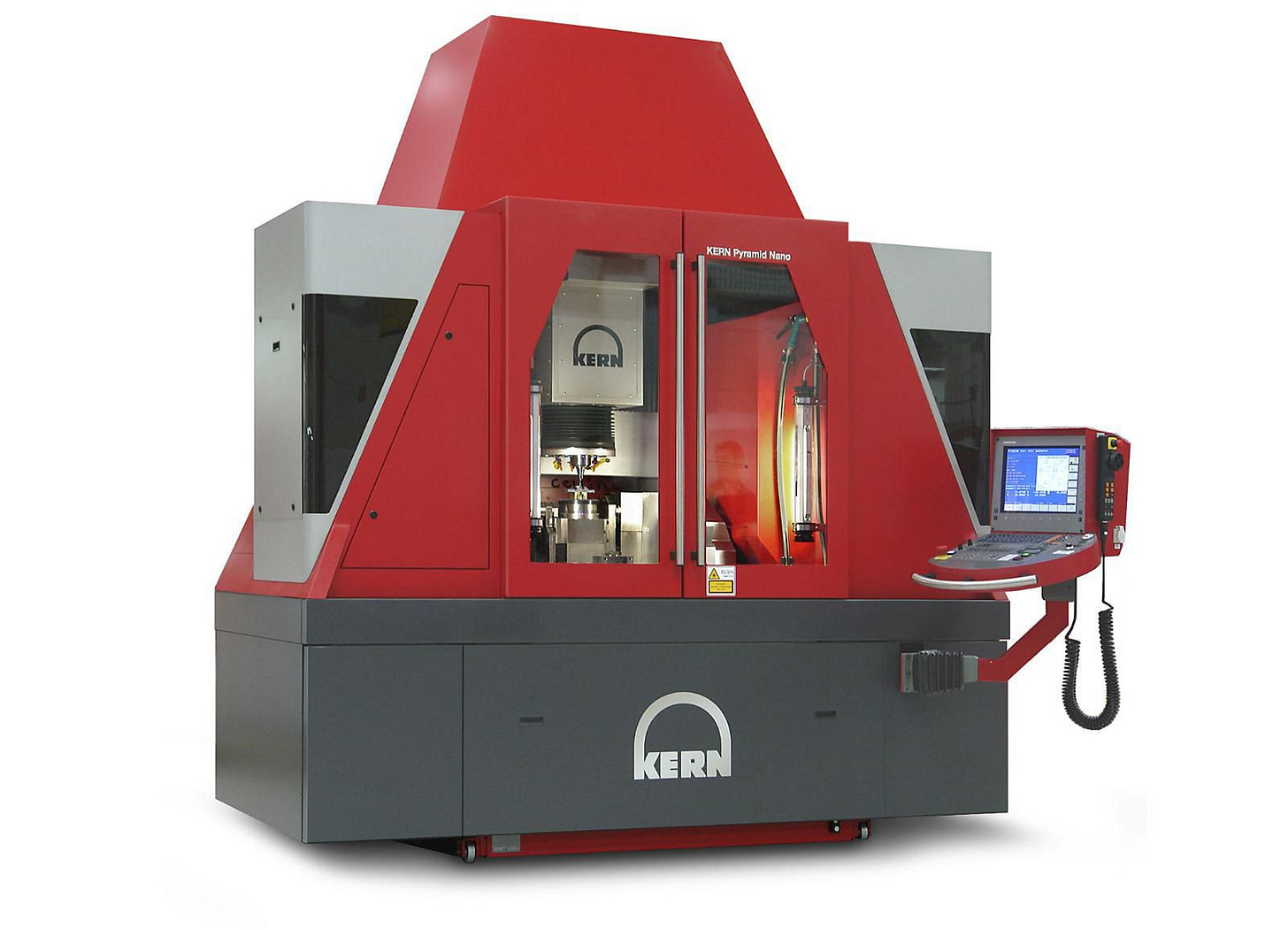

There are persistent rumours within the watchmaking community, corroborated by credible sources, that Rolex used, and then put up for sale, a KERN CNC machine specifically for scribing guilloché dials like the one in their new 1908 Cellini model.

The guilloché dial on the new Rolex Cellini is claimed by some Rolex employees/dealers as being produced “the traditional way”, implying a rose engine. But I can’t find any official statement from Rolex confirming this, and only note watch publications regurgitating this statement. So, Rolex maintains plausible deniability, I suppose!

—

Edit 22 September 2024 - some information from RJ Broer:

Now you know!

—

However, considering Rolex’s production scale and the extremely high consistency of their dials, it seems far more plausible that these patterns were created using CNC technology rather than a manual rose engine lathe they would love you to believe was used.

This method allows for the high level of precision and uniformity expected from Rolex, but it also raises ethical questions about how these dials are marketed. The implication that these dials are handcrafted, when in fact they are 100% machine-made, adds another layer of scepticism towards claims like this, particularly when considering other shortcuts Rolex has taken.

For instance, the faux chatons in some of their movements - gold-plated countersinks rather than genuine gold inset chatons - further exemplify their balancing act between traditional craftmanship appeal and the industrial efficiency they are known for.

The State of Guilloché, role of key suppliers: Metalem, Comblemine, and Décors Guillochés

To truly understand the state of guilloché today, we must consider the role of major suppliers like Metalem, Comblemine, and Décors Guillochés. These companies are at the heart of guilloché production, crafting dials for some of the most prestigious watch brands.

Comblemine is particularly renowned, providing dials for both smaller independent watchmakers and larger brands. However, this widespread use of their dials leads to a certain homogenisation - when stripped of branding, it can be difficult to distinguish a dial from Sartory Billard, Schwarz Etienne, Grönefeld, Fleming or even larger brands like Audemars Piguet.

Décors Guillochés, under the direction of Yann von Kaenel, similar to Comblemine and Metalem blends traditional techniques with modern methods. While von Kaenel’s atelier is famed for its traditional engine-turning expertise, the company also supports stamped dials (such as the dials they created for the AP Code 11.59) and CNC technology to meet the demands of larger production runs. This dual capability allows them to cater to a wide range of clients and price points, but it also dilutes the uniqueness that handmade guilloché dials traditionally embodied.

Craftsmanship vs. Industrial Production

Despite the prevalence of these suppliers, a few brands maintain dedicated guillochage ateliers, preserving the traditional craft at the heart of their production. Breguet, for instance, probably operates the largest guillochage workshops in Switzerland, producing dials that are genuinely handcrafted using rose engines and straight-line lathes.

Patek Philippe is another brand that, while sometimes blurring the lines between handcraft and modern methods, still upholds a strong tradition of in-house guillochage, particularly on their high-end models such as some world times but also produces many stamped guilloche dials which many collectors have criticised too.

Both Patek and Breguet typically indicate their hand made dials by including the word “a Main” or just “Main” next to Guilloché, indicating these are handmade items (“a Main” is French for “by Hand”). For dials from Comblemine or Voutilainen you are also looking for wording such as “Hand Made” or “by Voutilainen” to indicate they are made in the higher end atelier operating manual Rose engines. If a dial is just marketed as Comblemine or Metalem, it is most likely to be CNC machined - but some brands simply like to keep a clean dial, so this is never a guaranteed fact either!

Other brands such as Jaeger-LeCoultre, Louis Vuitton (with their La Fabrique du Temps manufacture), and Chronoswiss also invest heavily in maintaining their own guillochage workshops and “savoir faire” department. These ateliers are dedicated to the traditional methods and craft, ensuring their guilloché dials are not only visually distinct but also true to the craft's artisanal roots. We unfortunately typically only see this craft in the top-end pieces from these brand (JLC for example uses CNC for lower end models).

This dedication to craftsmanship is increasingly rare in an industry that often prioritises efficiency over authenticity, making these brands stand out for collectors who value genuine craftsmanship.

The Homogenisation and loss of craftsmanship in Guilloché

The lack of distinction is increasingly problematic in today’s market, where the visual appeal of guilloché is undermined by its ubiquity. The proliferation of similar-looking guilloché dials, particularly those produced by shared suppliers like Comblemine and Metalem, has led to a growing sense of fatigue among collectors.

This sentiment reflects a broader trend: as the hype around independent watchmakers begins to subside, there is mounting pressure on brands to deliver something truly unique. Simply offering another guilloché dial, no matter how technically proficient, is no longer enough to satisfy a market that craves both innovation and authenticity as well as embracing traditional craftsmanship.

Audemars Piguet’s Code 11.59 series, is another interesting direction brands are taking. It features stamped dials created using hand made pattern dies by Décors Guillochés. And while the pattern is quite unique and attractive, the industrial means of production to many collectors doesn’t match the price tag or exclusivity of a brand like AP.

This practice of using more and more machine made or industrial alternatives to traditional craft, along with the advances in machines to produce a high quality finish or replicate different traditional approaches, makes it increasingly difficult for even seasoned collectors to discern the true craftsmanship still remaining.

As brands keep blurring the lines between traditional craftsmanship and modern production methods, it becomes more important than ever for collectors to be discerning and critical of the narratives presented to them.

The allure of guilloché lies both in its visual intricacy as well as in the story and method of its creation. I would like to challenge the industry’s narratives, ensuring that terms like “guilloché” retain their true meaning and that collectors receive the authentic craftsmanship they are promised.

We should demand clearer labelling and marketing communication from brands, if a dial (or movement) doesn’t feature the words “a Main” or “Hand Made” we should just assume some shortcut was used. Even if it was made “by hand”, was it done by a true master or using a setup that requires far less skill from the operator and allows more industrial production?

Appreciation and understanding by watch collectors is crucial for this, and we must continue to demand the real deal from watch brands as they will continue to find shortcuts that short-change buyers, especially buyers who are less educated in identifying the hallmarks of artisanal crafts.

We have seen the same thing happen to movement finishing where interior angles and hand applied anglage was rapidly disappearing but has now found new appreciation with discerning collectors. Independents in particular are sensitive to this, even if some brands like Biver have recently gone slightly overboard with a focus on finishing techniques - look at the smorgasbord in their new Automatique line. By the way, I strongly suspect has used CNC to create the Guilloche patterns on the bridges and rotor:

I hope the traditional craft of guilloché continues to be practised by brands and passed on to new watchmakers, rather than being slowly replaced entirely by modern “equivalents” as the pressure to reduce costs while increasing production numbers and margins ever continues.

-A Watch Critic

End note

Hello, it’s me again. I’m trying to encourage A Watch Critic to start writing some more on Substack - So please subscribe to his Substack if you want to see more of this in-depth critical stuff. Otherwise I’ll have to keep nagging him for guest posts!

Thanks for reading. Hit the ❤️ on your way out ✌

You really ought to find a technical adviser. Anyone who has any amount of experience with this kind of work can tell you that not a single one of Atelier Wen's claims about the challenges involved in manufacturing the dials are correct.

In general this article is a good summing-up but I want to point out a few things.

The claim that the guilloche machines lose calibration if left unattended for more than 15 minutes is ridiculous. A rose engine is just a lathe which operates on a slightly different principle. It is a machine tool which has deterministic results for given inputs regardless of how long it has been left unattended. The only danger in leaving work unfinished on the machine is that the operator may forget what step they are in the phasing and indexing necessary for generating the pattern. Atelier Wen's claim may be some severe and negligent corruption of this potential issue.

A note on precision in guilloche - The precision necessary in a guilloche pattern is related to the fineness and intricacy of the pattern, and the depth of the guilloche cut. An extremely fine basket weave pattern as in Roger Smith's dials will have a depth of cut of 0.042mm. The depth of cut varies depending on the pattern and the angle of the cutter, in Roger's case a 3 bar basket with a 1.2mm pitch pattern bar, and 160 degrees of included angle on the cutter. Let's presume 10 percent of cut depth is allowable without being noticeable, then 0.004 micron is the tolerable error. Already that is greater than Atelier Wen's claim of 2 micron required accuracy. Looking at, for example, the Perception V2 Piao dial, my estimation on the depth of cut is about .126. This is on the basis of a 22bump rosette and correlating the case diameter to the spacing of the cuts, and taking a conservative guess as to the cutter angle which I estimate at 140 degrees included. 10 percent of this figure is 0.012, 6 times the stated required accuracy.

Of course there are many other types of precision in lathes. Even in very precise manual turning lathes like those used for turning watch parts, like the schaublin 70, 2 microns of runout or centering is considered very good. For a rose engine such figures are unimageable and beyond that far beyond what is necessary.

As for the claims of effort or time requirements - you can take as long as you want to do a guilloche dial. If it is taking his shop 8 hours of continuous engine turning to produce these simple patterns, that is not a reflection of complexity or challenge. It is a matter of pace of work. A positive spin might be to call it deliberate, more realistically it's just slow. Or, someone somewhere is lying, or misunderstanding and re-interpreting something benign for marketing spin.

In general if someone refuses to be transparent about these things then there is something being hidden. If it was actually this difficult they would show the process in full.

Superbly put together piece, I salute you. Especially as I was critical and defensive against your critique when we discussed this at the time of the Revo launch. My apologies for that.