Illusions

Don’t let life’s illusions fool you into thinking you have nothing to be grateful for, because in fact, the opposite is true!

“Who has a better dress sense? You, your brother, or your best mate?”

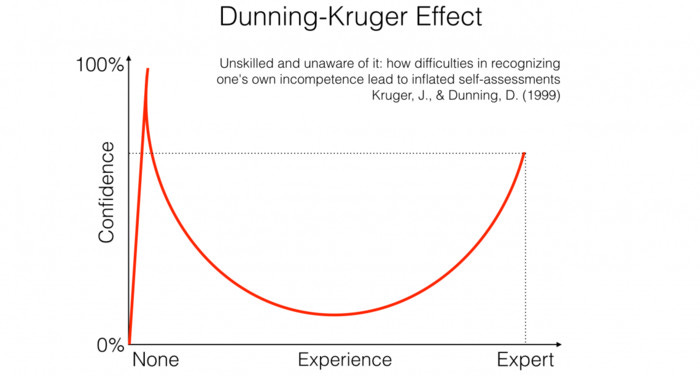

You might expect most people would reply, “me.” It will not be surprising to hear humans tend to have irrationally positive opinions about themselves, their choices and their decisions. There is plenty of research to support this view; On average, most people tend to hold beliefs about themselves regarding trustworthiness, intelligence, and even their sense of humour. A recent study even found people believe they use ChatGPT more efficiently and ethically than others!

The other one which will resonate with many, is how everyone believes they are excellent drivers - perhaps men more than women - and this is defined as Illusory superiority1 or the “better than average” effect.

Here’s a deep dive into desire for status a fundamental human motive - one thing you might be surprised to learn, is that people are not universally overconfident in all their abilities wherever they go. Instead, people adjust their overconfidence and factor in the impact of their specific social environment - in order to maximise their status. For example, in individualistic cultures like the USA, people overestimate their ability to lead others. In collectivistic cultures like Asia, people overestimate their ability to listen.

In other words, we even think we are better than ourselves. Funny enough, I have seen this play out in watch collecting too. The same people will emphasise a different one of their own traits depending on the audience. If they attend a local Redbar, they might be more inclined to adopt a “we hate flippers” mentality and describe how aligned they are with this view. Later, at some affluent collectors’ dinner, they will happily discuss their watches as “curated investments” which, strictly speaking is just bourgeois flipper culture… Just with larger working capital and longer holding periods.

One ingenious study asked participants how often they helped other people; then a while later, the researchers showed these people their own scores, but told them there were scores of “their average peer”. Not knowing these were their own scores, when they were asked to rate themselves again, they rated themselves higher than the average. In other words, they claimed to be better than themselves. 😂

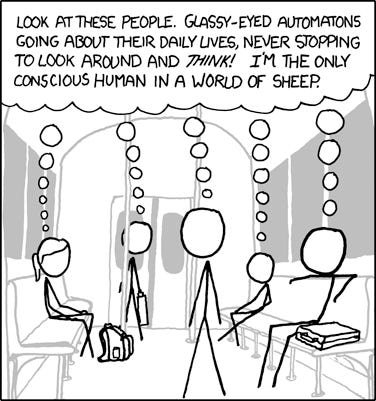

Another thing people do, is overestimate the influence which mass media has on others while underestimating the influence which mass media has on us. This tends to increase general support for censorship, because we think other people are sheeple who can’t handle certain information (or “misinformation”) - but we also think of ourselves as being independent thinkers who are more than able to critically evaluate all the information we come upon.

Unsurprisingly, everyone believes they are less susceptible to social biases than the average person. This recent study makes the point with two main findings in relation to people’s beliefs versus others: 1) Others are more likely to make decisions based on preconceived notions and preexisting beliefs, and 2) Others are less willing to update their views in light of new information. The researchers concluded:

“The more strongly people believed that biases widely existed, the more inclined they were to ascribe biases to others but not themselves.”

But… We don’t think we’re perfect.

The one aspect of life where people often believe they fall short is their social lives.

In this study, they show how people believe others are more popular, attend more parties, dine out more, have more friends, spend more time with family, occupy wider social networks, and possess larger social circles than themselves.

This is weird, right? Despite the fact that we hold inflated views about ourselves, we also believe our social lives are worse than everyone else’s - why is this the case?

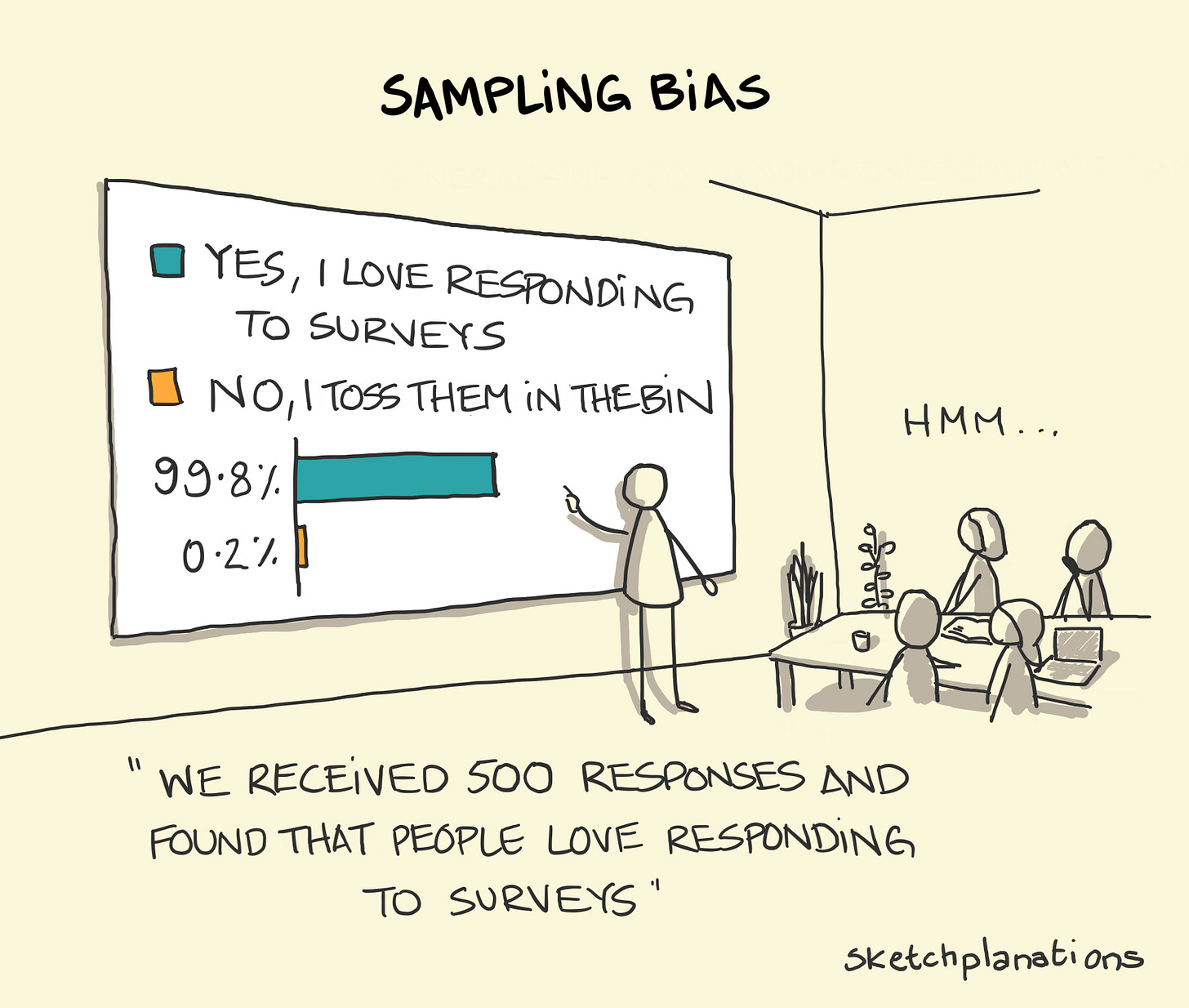

You might already know the answer… as it has something to do with another bias we have covered before… the spotlight effect, or, sampling bias2. It turns out, the standard we set for ourselves is biased by the most visible and prominent people in our lives. Even in any social circle. the most attention is paid to the popular ones. These popular people set the bar for what everyone thinks “other people are up to”.

Consider a thought experiment in which you sample 10 of your collector friends. 3 of them seem highly sociable, always at events, and they probably share many images from watch meet-ups, brand events and watch auctions to name a few possibilities. Another 3 seldom go out and are probably homebodies who are seen infrequently at watch gatherings; perhaps you see them a couple of times each year. The final 4 friends are similar to yourself - with supposedly ‘average social lives’.

The problem with our mental calibration is this: when we consider our own social lives, we tend not to compare it to the 3 homebodies. This is because we rarely see them anyway, so they are underweighted in our mental evaluation. We place some weight on the final 4 because perhaps we see them more often and we can relate to them more easily.

Comparatively, we overweight the initial 3 ‘socialites’ because they are always front and centre in the group chats and social media feeds. When we compare ourselves to them, our lives tend to seem rather dull compared to what we believe to be the ‘average.’ This average is a mental construct! As Daniel Kahneman said:

“What you see is all there is” or WYSIATI, is something Kahneman attributes to System 1 as well, and it is extremely influential in colouring our judgement. This is where we take in some data, and System 1 presumes that is the complete and definitive story.

Quick tale from WW2

My buddy Cliff made a comment on Instagram the other day, which reminded me of this story which highlights the value of known unknowns.

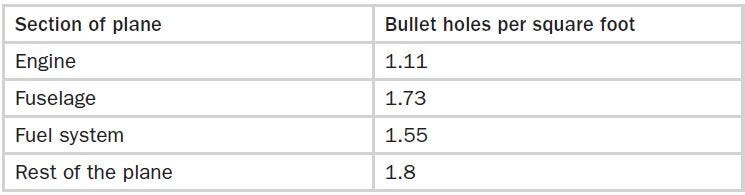

It is world war… and you don’t want your planes shot down in battle, so you install armour on them. Thing is, armour makes a plane heavier, and heavier planes are less agile in combat, and use more fuel. So, too much armour is a problem, and too little armour is also a problem. What is the optimum quantity of armour?

The military produced some bullet hole data from American planes which returned from engagements over Europe. Turns out, the damage wasn’t uniformly distributed across the aircraft. There were more bullet holes in the fuselage, not so many in the engines:

Perhaps you see the problem? Initially, they thought they were really smart… they would place armour on the areas which get hit the most, because they clearly had the greatest need, right? Wrong!

Abraham Wald was the genius who called it. Wald simply asked: “Where are the missing bullet holes?” The ones which would have been all over the engine casing, if the damage had been spread equally all over the plane… As Wald realised, the missing bullet holes were on the missing planes. The reason planes were coming back showing all the missing hits to the engine, is the planes that got hit as much in the engine simply weren’t coming back!

The armour, said Wald, should go where the bullet holes aren’t: on the engines. The large number of planes returning to home with a Swiss-cheese fuselage served, for Wald, as pretty strong evidence that hits to the fuselage can (and therefore should) be tolerated.

This is the same as when you sample hospital recovery data, you’ll find a lot more people recovered from bullet holes in their legs than people who recovered from bullet holes in their chests. That’s is obviously not because people don’t get shot in the chest; it is because the people who get shot in the chest don’t recover.

The point being, how we sample, and how we evaluate data, is as much about the stuff wee, as it is about the stuff we do not see.

The Friendship Paradox

The Friendship Paradox is the phenomenon first observed by the sociologist Scott L. Feld in 1991 that on average, an individual's friends have more friends than that individual. How is this possible?

For the same reason that when someone walks in to a room wearing a Dufour Simplicity, the average value of watches in the room would almost double:

Let’s do another thought experiment in which you sample 10 of your collector friends. 9 of these friends are just like you, and they have 10 friends. The 10th friend, however, is a super connected fellow, and he has 100 friends. The math is simple: on average your friends all have 19 friends, and you only have 10 friends:

These examples demonstrate the Pareto principle, and they distort so-called averages in our social lives. The same is true in watch collecting ad on social media too. 80% of tweets come from only 10% of users, at least in 2019 anyway. The “1 percent rule” on the internet goes like this:

Only 1% of people create the content, which is edited by 9% and is read or ignored by 90%.

So in short, the super connected people who drive the friendship paradox tend to drive our mental averages, and the more ordinary people in our social circles tend to be overlooked.

You might see plenty of F.P. Journe watches on Instagram daily, but when last did you see one out in the wild? How about a Roger Smith, or an AkriviA? At best I see a few Submariners and GMTs, and granted being in London might hinder these probabilities due to safety issues - but still, even when I speak to people in Geneva or Dubai, the frequency of randomly encountering high horology pieces is completely skewed vis-à-vis the expectations created by social media.

By evaluating ourselves and calibrating our world view to such unnecessarily high standards, we tend to set ourselves up for unflattering evaluations of our own watch collections and social lives.

People seldom post photos of themselves living a normal day, riding a bus, or sitting at home having dinner with their family… all while wearing pedestrian watches like a Rolex Air King. The introverts, and the risk-averse, are simply not visible... and so we aren’t going to bother comparing ourselves to them.

Concluding thoughts…

When people believe that their lives were more impoverished than others, socially or otherwise, they tend to report lower levels of life satisfaction. A healthy view of others’ lives can improve our own mental health too.

What also helps, is to differentiate between how we measure our own character and differentiate this from tangible outcomes. Yes, we may hold self-serving views and overweight our own estimates of intelligence, morality and ability, yet we still look outward as we evaluate other people’s outcomes such as watches, wealth and social popularity. This calls for some reflection … particularly with regards to self-confidence.

You are successful, you may have a great job, a family who admire and rely on you, a company which goes from strength to strength due to your hard work. You may have excellent qualifications, parents who are proud of you, siblings who look up to you, friends who value your counsel, communities who you serve, and are glad to have you… You may buy groceries for the old lady up the road or give charity to the same homeless man daily on your commute. You have a lot to be proud of, and many sources of self-confidence.

You do not need external validation. The ego must be kept in check, and any desire to seek validation of your own value or righteousness can become poisonous to your mind. Life would be boring if it was too easy, you’d have nothing to aspire to, or to celebrate.

Don’t let life’s illusions fool you into thinking you have nothing to be grateful for, because in fact, the opposite is true!

In the field of social psychology, illusory superiority is a condition of cognitive bias wherein a person overestimates their own qualities and abilities, in relation to the same qualities and abilities of other people.

In statistics, sampling bias is a bias in which a sample is collected in such a way that some members of the intended population have a lower or higher sampling probability than others. It results in a biased sample of a population (or non-human factors) in which all individuals, or instances, were not equally likely to have been selected. If this is not accounted for, results can be erroneously attributed to the phenomenon under study rather than to the method of sampling.

We are both about to see a Journe and an Akrivia in the wild. Can’t wait my duuuuuuude!!!!

Great article! It’s Sunday evening, I live in Paris and I am at home reading your article and not seeing any friends, should I worry to be the one guy that has less friends than his friends 🤣🤣