Behind the Scenes at La Fabrique du Temps

I visited Louis Vuitton's watchmaking factory, and have some thoughts to share

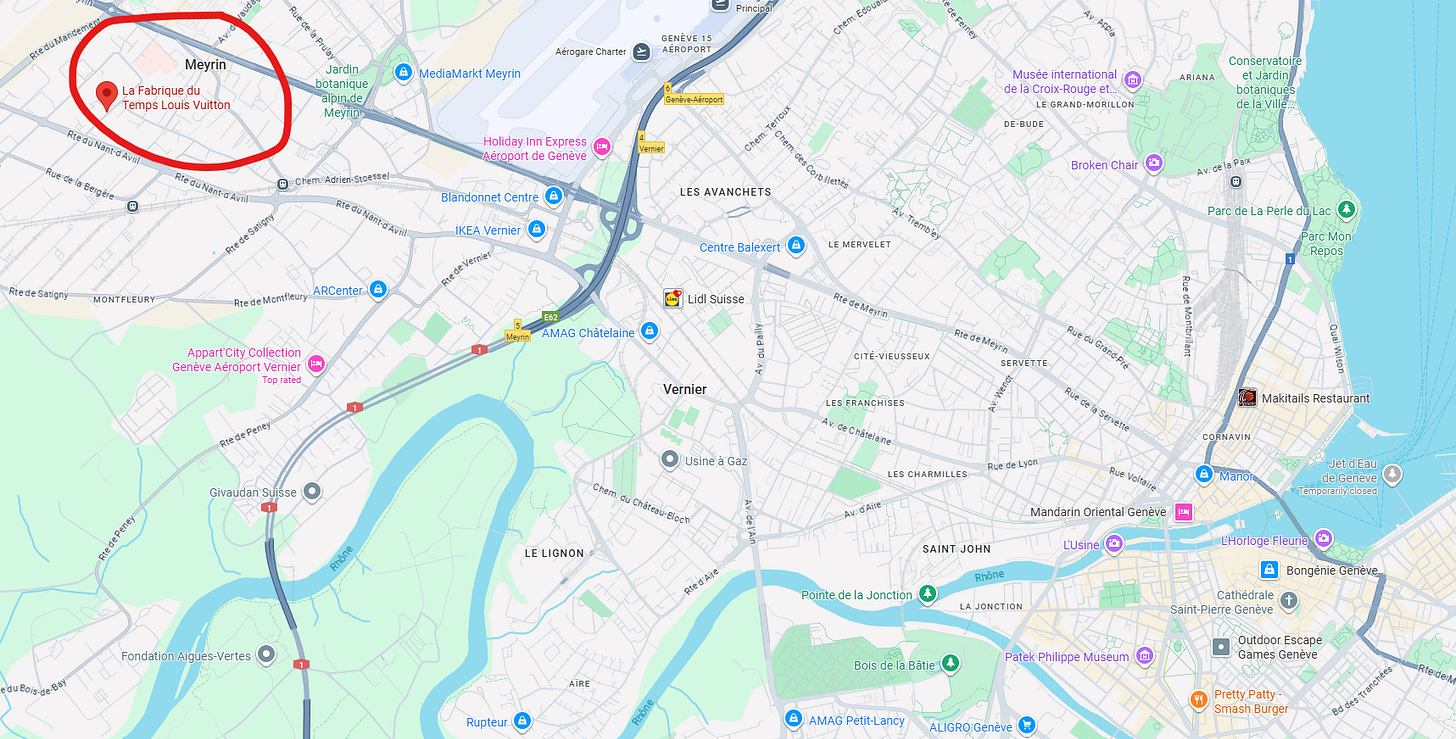

Have you even heard of Meyrin? Honestly, I hadn’t, until I went there to visit La Fabrique du Temps (LFdT) … right next to the Chopard headquarters, as it happens. This visit to Louis Vuitton’s watchmaking nerve centre was quite informative because while I’d previously read others’ stories about LV’s watchmaking HQ1, I actually learned a few interesting …