Nobody buys watches to tell time anymore...

...and the luxury goods market is collapsing just as experiences inflate at historic rates. Why are the ultra-wealthy trading tourbillons for time?

At the end of every calendar year, the watch world does its annual reflection thing. Jack Forster covered technical highlights of 2025, and Chris Hall went into individual brand scoring. So what was left?!

I figured there’s always the weirder, messier questions about what’s actually happening to luxury goods as a category, or why the Swiss watch industry is suddenly admitting it’s not in the business of telling time anymore, or what it means that your Nautilus lost half its value while Wimbledon tickets have doubled in price.

So today we will go back to SDC’s bread-and-butter, which is the socioeconomic and psychological stuff that doesn’t fit neatly into “technical reviews” or “brand analysis.” This is the territory where watches intersect with consumer behaviour, class anxiety, interest rates, Chinese market, gold buying, and in today’s episode, a realisation that rich people are divesting from physical assets and piling into experiences at rates that make no sense until you look at the data.

What follows is a somewhat sprawling attempt to connect dots between watch market corrections, art auction collapses, hotel rate inflation, supplier bankruptcies, and why Hermès seems to have avoided all of this. I’ve thrown in some predictions about what breaks next, because why not. Some of this will be wrong, but so what? 😂

Fair warning - this gets into interest rate policy, superfakes, family office asset allocation, and ayahuasca retreats. If you came here expecting a ranking of the top 10 watches of 2025, this is probably not for you. If you are curious about why Georges Kern can sit at a CEO Round-table at Dubai Watch Week and declare that nobody buys watches to tell time anymore, and why that statement is both obvious and terrifying… well, that’s what we’re here to explore.

Estimated reading time: ~28 minutes

Timekeeping is over

At Dubai Watch Week Georges Kern from Breitling said: “Nobody is buying an analog watch to read time. Nobody.” Carl Friedrich Scheufele from Chopard agreed: “It’s more an adornment than an object that tells time.”1

In some ways, this is a weird thing for watch company CEOs to say. I mean, it’s technically true, but admitting it publicly feels like crossing some kind of metaphysical Rubicon.

Yet, as the average watch enthusiast knows, they’re absolutely right, which makes everything that follows more confusing, but also more obvious. The Swiss watch industry is finally coming around to the realisation that it’s no longer in the timekeeping business, but in the feelings business. And the fun part is that most of them have no idea what their brands actually make people feel.

You could view this as the natural endpoint of all luxury goods marketing, except that once you admit you’re selling pure emotion and not function, you’ve entered a very dangerous game. Because emotions, unlike magnetic escapements or soft-touch pushers, are really hard to manufacture - let alone at scale. And once you’re competing purely on emotion, you’re competing with literally everything else that might make someone feel something; that includes jewellery, art, movies, vacations, therapy, longevity clinics, sporting events and just... experiences that cannot be replicated or faked.

Which brings us to the numbers, which are bananas.

Are watches too expensive?

Today, Rob Corder at WatchPro asked exactly that question. His answer is carefully hedged, though; Swiss watch prices have exploded over 20 years (244% increase vs 59% inflation since 2005), but recent increases have been more moderate. Rolex’s average price rose just 10% from 2019-2024 vs 25% CPI inflation, Breitling under Georges Kern is up only 15%, and TAG Heuer actually fell.

Rob’s conclusion is that the industry isn’t raising prices as aggressively as people think, and brands deliberately cultivate perceptions of expensive watches because that’s how the Veblen effect works - higher perceived prices tend to increase desirability, so why would they correct the narrative?

He’s obviously correct about the numbers, but I feel he’s missing the forest for the trees. It doesn’t matter whether watch prices rose 10% or 25% in the last five years when the middle class essentially tapped out. Whether that’s because of watch price inflation, general inflation eating discretionary spending, or structural collapse in demand … it doesn’t change the end result. The aspirational buyer can’t really participate anymore, and the data from late 2025 proves this bifurcation2 is accelerating, not slowing.

Luxury asset correction

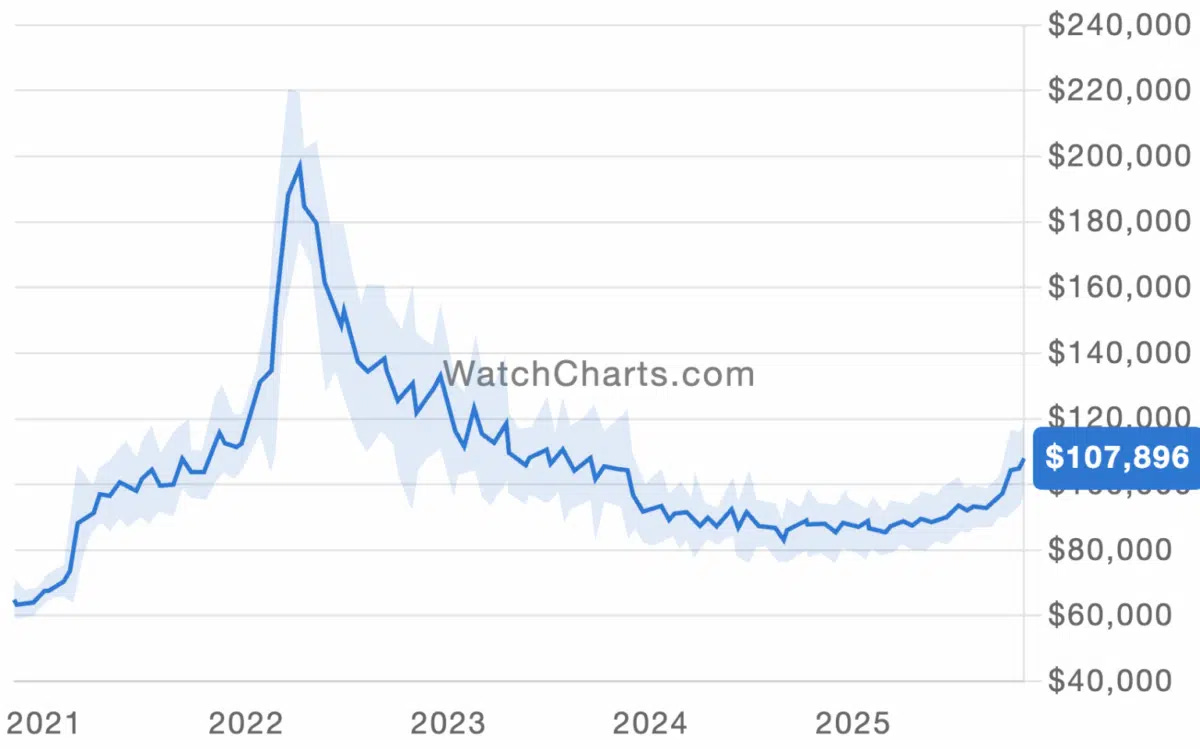

Let’s start with watches, since that’s what prompted this whole thing. The Patek Nautilus 5711 which, let’s be honest, epitomises watch speculation mania, peaked at ~$200,000 in 2022. Today it trades around $100,000. That’s a ~50% drop. If you bought one at the top thinking it was “alternative asset class investing,” well, congratulations! You eventually discovered that watches are not, for example, bonds.

The overall secondary market data is even worse; by Q2 2025, prices had fallen for 13 consecutive quarters, and value retention across the industry had tanked3. Excluding Rolex, Patek, and AP, the average watch now trades at -31% or worse relative to retail. Again, we see bifurcation - “investment-grade” vs instant depreciation.

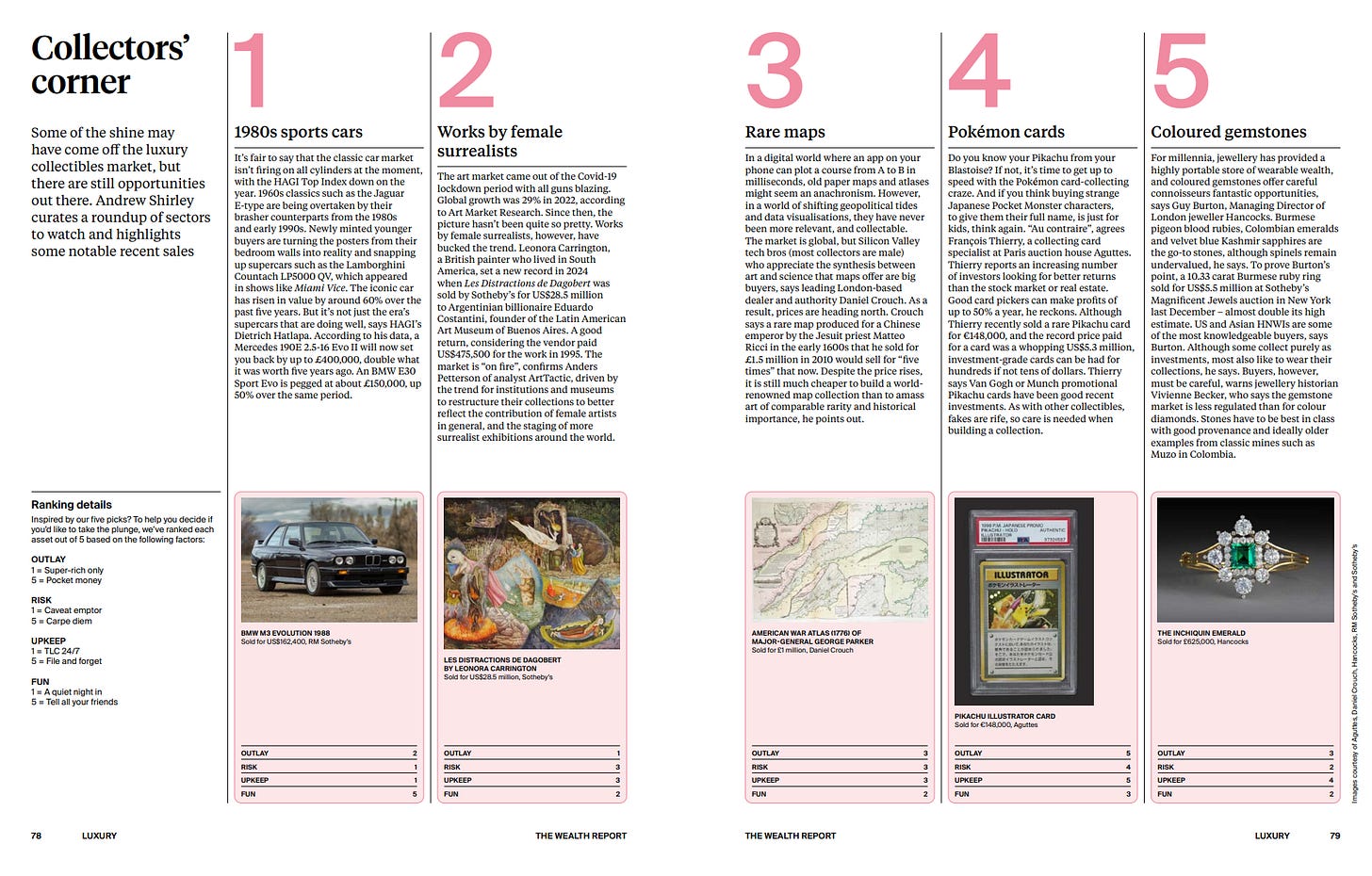

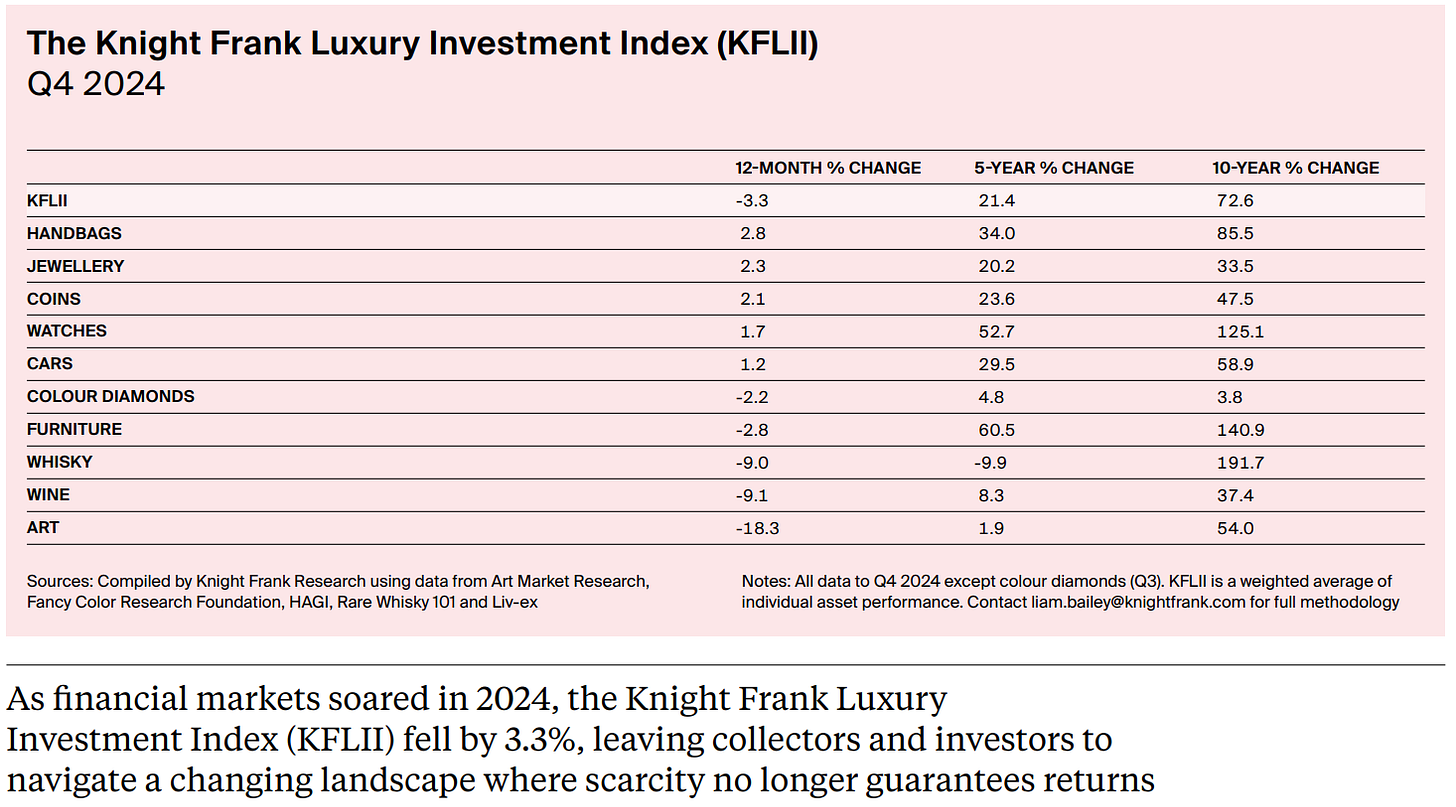

But watches are the least crazy part of this story; as you can see, they don’t even feature in the “collectors’ corner” above! The Knight Frank Luxury Investment Index tracks all the stuff rich people convince themselves are investments, and this is down -3.3% in the last year. Now that doesn’t sound too bad until you realise that:

Wine is down 9% and Bordeaux first growths (Lafite Rothschild, Margaux) are down 20%

Fine art auction sales at the major houses (Christie’s, Sotheby’s, Phillips) contracted by nearly 48% from the 2022 peak of $7.8 billion to roughly $4.1 billion in 2024 (there are varying figures out there but call it 50%4)

Classic car values are softening across the board

Rare whisky down 9%

It gets more interesting, when you look at what’s gone up:

Luxury hotel rates: up 90% since 2019

Le Bristol Paris (finest hotel in Paris): up 100% since 2019

Wimbledon five-year debenture (guaranteed Centre Court seat): from £50,000 to over £100,000

Super Bowl suites: up to $2.5 million

Met Gala tickets: doubled

Three-Michelin-star meals: up 78% (the correspondent from The Economist paid $500 at Benu in San Francisco and rated it “Maybe?”)

Housekeepers in Palm Beach: $150,000/year

In essence, this is like some sort of inversion of what “luxury” means. The stuff you can put in a vault or wear on your wrist, is deflating. The stuff you experience once and can never get back, is inflating at rates that would make Jpow nervous.

Veblen traps

The economic theory part is actually pretty straightforward, and we’ve covered it on SDC a few times. Thorstein Veblen argued that luxury depends on two things: scarcity and “rivalrousness.” A good is truly luxurious by being expensive, but also because one person’s consumption prevents someone else from having it.

The problem, and this is now an existential problem for luxury goods, is that physical goods have kinda lost their rivalrousness. You can buy a “superfake” Hermès bag for a few hundred bucks that is virtually indistinguishable from a $20,000 genuine one. Lab-grown diamonds are molecularly identical to mined ones. The best watch replicas require literal microscopes to detect, and that’s only if you are able to open them up. When the watch forum nerds talk about “tells” that reveal a fake Rolex, they’re discussing the angle of printing on a date wheel that requires 10x magnification to see. Not to argue semantics or lay down a challenge here… all I am saying is that this is not a sustainable basis for signalling status!

But… and here’s where we get to why experiences are eating the world… you cannot fake a live story on Instagram from the Royal Box at Wimbledon. You can’t replicate the fact that you were on that specific private yacht on that specific weekend with those specific people, because time only moves forward and physical capacity is finite.

Experiences have what you could call “cryptographic proof” of status. They’re “unforgeable”, and given so much else can be faked nowadays, that’s worth paying for.

Side note fwiw: There’s a separate issue here about the “superfake crisis” that luxury brands need to wrestle with. If a cheap fake is indeed indistinguishable from a $20,000 genuine item to everyone except the wearer, then the $20,000 price is purely about self-deception. You’re paying to know something nobody else can know, which is... not nothing, but it’s a much weaker value proposition than “everyone knows I’m rich because I have this thing.” Anyway, I digress…

Financialising everything was a bad move

Let’s talk about interest rates for a second, because the money angle is relevant too. For basically a decade, we lived in a ZIRP (zero interest rate policy) world where the opportunity cost of holding any asset was negligible. If you had a $10 million art collection sitting in a warehouse, that would be just fine, because the alternative was buying bonds that yielded 0-1%. If you had a $5 million watch collection in a safe, that was cool too, since cash earned nothing anyway.

Now although Jpow cut rates again last week… in general, rates normalised since ZIRP, and as a result, the maths changed too. If you can get decent-ish returns in private credit or even just 3.5-5% in Treasuries, the carrying cost of holding non-yielding luxury assets becomes painful. That’s because you’re still paying for things like insurance, storage, maintenance, and security (all go up with inflation), while your asset generates zero cash flow. Plus, in the current market, it now has a decent chance of declining in value. This is what family offices call “negative carry,” and it’s not a great place to be.

So now we’re seeing family offices (which are basically hedge funds for families) tell their clients to, loosely speaking, “sell the wine cellar, deploy the capital into private credit or real estate, and use the yield to fund lifestyle experiences.” This makes economic sense, right?! You’re trading negative-carry physical assets for positive-carry financial assets, and using the distribution to buy experiences that actually make you happy.

It’s the ultimate financialisation since you’re treating your lifestyle as a strategic asset allocation decision. This might even be the most rational thing ever, or perhaps a sign that capitalism has entered its baroque phase. (Probably both!)

Watch market as securities fraud (tangent)

Between 2020-2022, people started talking about watches as “alternative investments” and “passion assets” that could generate returns. They cited historical appreciation, and they even built indices and created fractional ownership platforms. Basically they made it sound like index funds and bonds, but fun - lol.

This was, you know, suspicious; mainly because watches don’t produce cash flows 😂. They don’t have terminal values based on discounted future earnings. They’re consumer goods that some people will pay more money for than other people, based on purely subjective preferences that can change overnight.

But anyway, once you financialise an asset class (i.e. tell people it’s an investment and not consumption), you create a feedback loop which goes like this:

Prices go up → people buy for capital appreciation → prices go up more → financial analysts write reports → more people pile in → prices bubble → something breaks the narrative → everyone sells at once → prices crater → then some people think it’s over so they pile in again → the people who missed the first round sell → prices crater again → the ones who never got to participate pile in again → they realise it’s not all that → prices crater... you get the idea.

The watch market is just about completing that entire cycle in 36 months, except perhaps Journe, which is still running its course. But certainly everyone who bought a $300,000 Patek thinking it was “portfolio diversification” is discovering that it’s actually just an expensive way to tell time that they could have gotten for free on their iPhone.

Is this actually securities fraud? Well, not legally, since watches aren’t securities, authorised dealers aren’t broker-dealers, and ‘this will hold value’ isn’t quite the same as ‘this will generate returns.’ But morally? Brands absolutely knew they were selling to speculators more than legit ‘end users’. People were almost incentivised to live beyond their means, and they knew speculators were flipping for instant profits. They kept the charade going as long as possible because it boosted their numbers. Then when it crashed, they blamed ‘market conditions’ and walked away with collectors holding the bag.

If this had been real estate or equities, someone would be facing regulatory consequences. But because it’s watches, everyone just shrugs. The industry completed a textbook speculative bubble cycle in 36 months, learned nothing, and will probably do it again with the next hype object.

Consumer trends data

Okay, let’s bring in some consumer data, because it helps to explain why this psychological shift occurred when it did. I accept that this is US-centric, but I have yet to find a decent parallel-source to look at other regions in the same light; if you have any suggestions, drop them in the comments. Anyway, New Consumer’s 2026 trends report tells us some interesting things…

First: 42% of consumers say rising prices are the most important problem in the US5 - this is by far the highest concern. Even with inflation cooling to ~3%, nearly half still feel prices have increased ‘a lot.’ Wages have barely kept pace (+22.6%) with cumulative price increases (+23.5%) since 2021. This is the “squeeze” which is hitting aspirational luxury buyers… the very people who used to buy entry-level Omegas and Longines, have tapped out. Remember when we previously discussed ‘the middle market’ facing difficulty? Here it is!

The Swiss export data from November 2025 proves this as well; while total volume collapsed -10.9%, the only segment that grew, was watches priced CHF 200-500 (Tissot PRX territory), which rose +7.2% in volume.