Ming's Radical Watchmaking Playbook

Subsidiary brands, investor-funded watches, and an integrated bracelet watch with no logo

Ming has always operated slightly ‘adjacent’ to the traditional Swiss watch industry. The team is geographically dispersed, they appear to be ‘digitally native’ in how they handle things, and their watches are aesthetically distinct. At Dubai Watch Week, Ming Thein (Founder and Creative Lead) and Praneeth Rajsingh (CEO) sat down with Andy Hoffman1 to pull back the curtain on how they’re transitioning from boutique enthusiast favourite to sustainable business - all without losing what Praneeth called the “irrational passion” that fuels this whole industry.

This was one of the most candid business discussions you’ll ever hear from an independent brand, and I thought it would be worth discussing some of their provocative ideas about watchmaking and where we might be heading.

Estimated reading time: ~12 minutes

The pivot to in-house engineering

Based on what I heard, the most significant operational shift for Ming is the move away from external engineering partners. Ming Thein, a photographer by trade, apparently taught himself CAD and now handles internal construction and engineering personally.

Why would anyone do that? Well, previously there was a disconnect between 2D design and 3D execution; what this meant was external partners often misunderstood critical design elements or got non-critical tolerances wrong, which led to painfully long feedback loops. Ming now operates a “farm” of five 3D printers in their own office to rapidly prototype components2. This allows them to iterate designs internally before sending files to their team in Switzerland. This team manages the complex web of production partners (not 100% Swiss), alongside Praneeth, who mostly deals with inputs on cashflow, costs, and timing.

The result has been what Ming calls a “Fifth Generation” design language, characterised by complex “internal packaging” that external-first engineers might have deemed impossible or impractical if asked to try it for the first time.

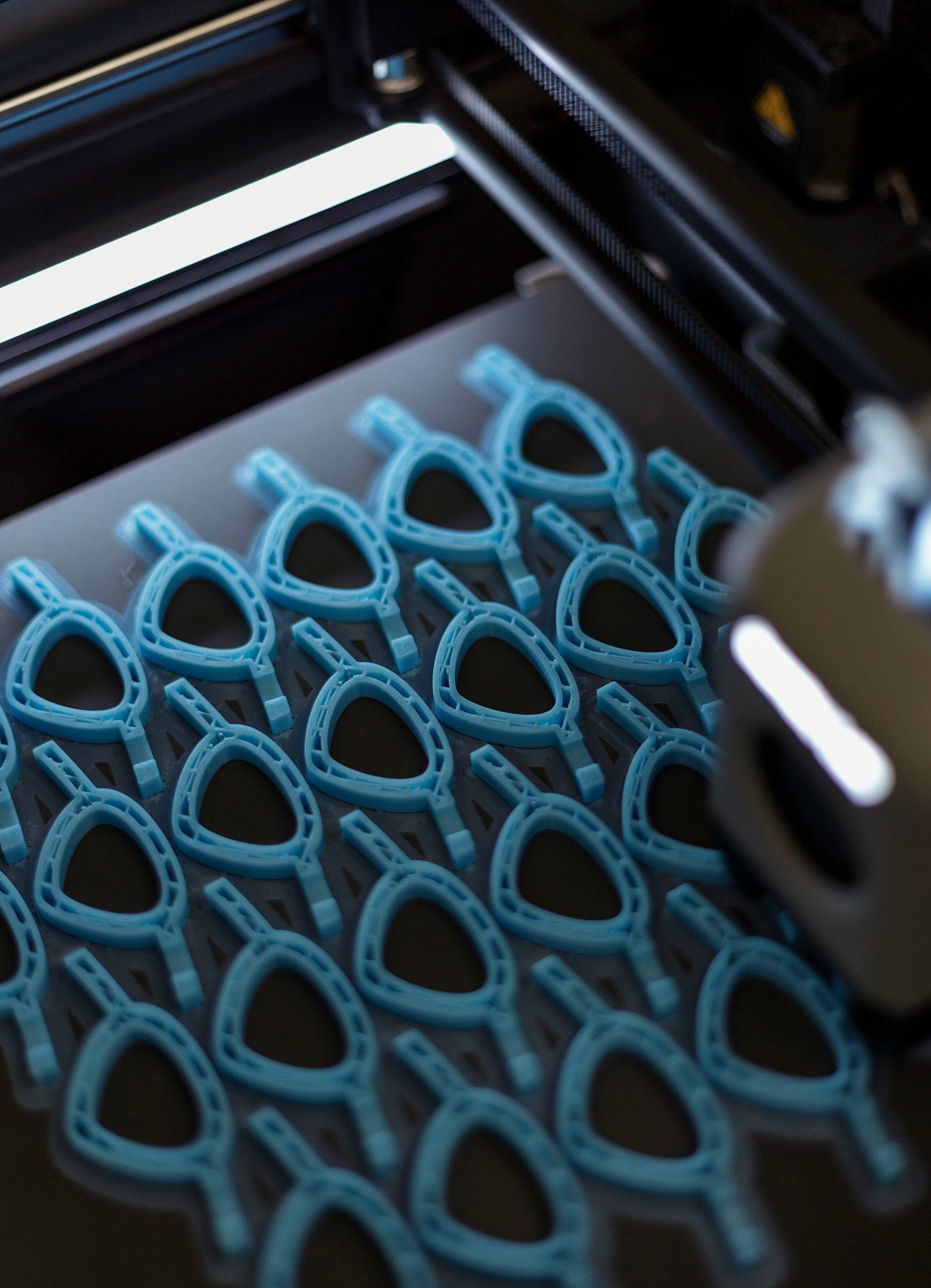

Ok, quick tangent; I asked Praneeth for some random but cool images for this post - and asked for a description as well. He kindly shared these two images, along with a description which I think you’ll enjoy:

“Both images show event collaterals or visual merchandise being 3D printed in our KL office. For anyone who visited us during Geneva Watch Days, WatchTime New York or Dubai Watch Week last year - they may recall us giving out lumed Bobnoses and a Polar Bear mascot at our booth. This is how they’re made. And since you’re no doubt wondering what the hell a Bobnose is - the polar bear’s name is Bob and the MING logo is his nose. Bit of inside baseball… :) ”

Polymesh

A decent chunk of the conversation revolved around the Ming Polymesh bracelet, which is a 3D-printed titanium bracelet consisting of 1,693 components (mostly printed as a single unit).

Ming described the tactile feel as “mercury stuck together” or “titanium lingerie” - I felt one myself at Dubai Watch week, and it definitely has a silky, draping quality that photography typically fails to capture due to what Ming himself describes as “a lack of stereoscopic depth” (we see with two eyes, and a camera ‘sees’ with one, so it’s hard to capture the essence of this bracelet in an image).

They also made an audacious comparison to the first iPhone, because this bracelet represents a new ‘genre’ of product that changes how we view manufacturing constraints. It essentially moves beyond hand-stitching or machining into a realm where additive manufacturing creates geometries which are impossible to create by any other means3.

Despite feeling delicate in person, I learned from this interview that the bracelet apparently handles around 100kg (1000 Newtons) of force before failing; and the bracelet isn’t what breaks, it’s the spring bar! Whether you buy the iPhone comparison or not, the engineering here is definitely pushing boundaries.

The shadow of Cupertino

Most interestingly for me, the benchmark for manufacturing excellence in the conversation wasn’t Patek or Rolex... it was Apple!

Ming mentioned the Apple Watch Link Bracelet (steel) and the Ultra’s sapphire crystal as marvels of production. He noted that the finishing on Apple’s relatively affordable bracelet or the complex machined sapphire on a mid-range Apple Watch would cost thousands of francs if produced via traditional Swiss supply chains.

This is rather underappreiated context for us watch nerds; the lesson here is that Apple proves “best-in-class” manufacturing exists, but it requires a scale (millions of units) that independent watchmaking simply cannot match. Ming’s challenge, as he sees it, is to achieve that Apple distinctiveness within the constraints of small-batch production (which is ~100-500 units over a product’s lifetime for Ming, according to Praneeth).

This is a fascinating tension, don’t you think? I mean, the Swiss industry often positions itself as the pinnacle of manufacturing excellence with all their finely finished parts and micromechanics... And sure, with a select few hand-finishing techniques, that may be true for now. But when it comes to precision machining at scale, the consumer electronics industry has clearly left traditional luxury manufacturing in the dust. It’s a humbling comparison that more watch brands should probably be thinking about.

Financial engineering and project finance

Another insightful segment for industry watchers was the discussion on capital. Traditional banks require hefty deposits for credit lines (making them essentially useless), and venture capital demands equity and control (which threatens creative independence).

Ming’s solution is a project financing model; instead of selling equity in the company, they allow qualified investors to fund specific watch projects. Investors put up the capital for a specific run (like a new model launch) and get a return based on the sales of that specific watch.

This solves the cash-flow mismatch inherent in watchmaking, where suppliers need payment months before customers buy the watch, without diluting Ming’s ownership or creative control.

We will come back to this in more detail later on.