The Decay of Luxury Watchmaking

Exploring the chasm between horological excellence and marketing-driven mediocrity.

This is a brief exploration of modern watch creation practices, delving into a contentious issue that’s quietly reshaping the industry, particularly in the last decade or so. What follows is a tale of two philosophies. One embraces efficiency and market responsiveness, and the other upholds the timeless standards of we will call horological excellence. As we’ll see, the choice between these approaches is far from academic - it cuts to the very heart of what it means to create true luxury.

Estimated reading time: ~ 10 mins

The Siren Song of Efficiency

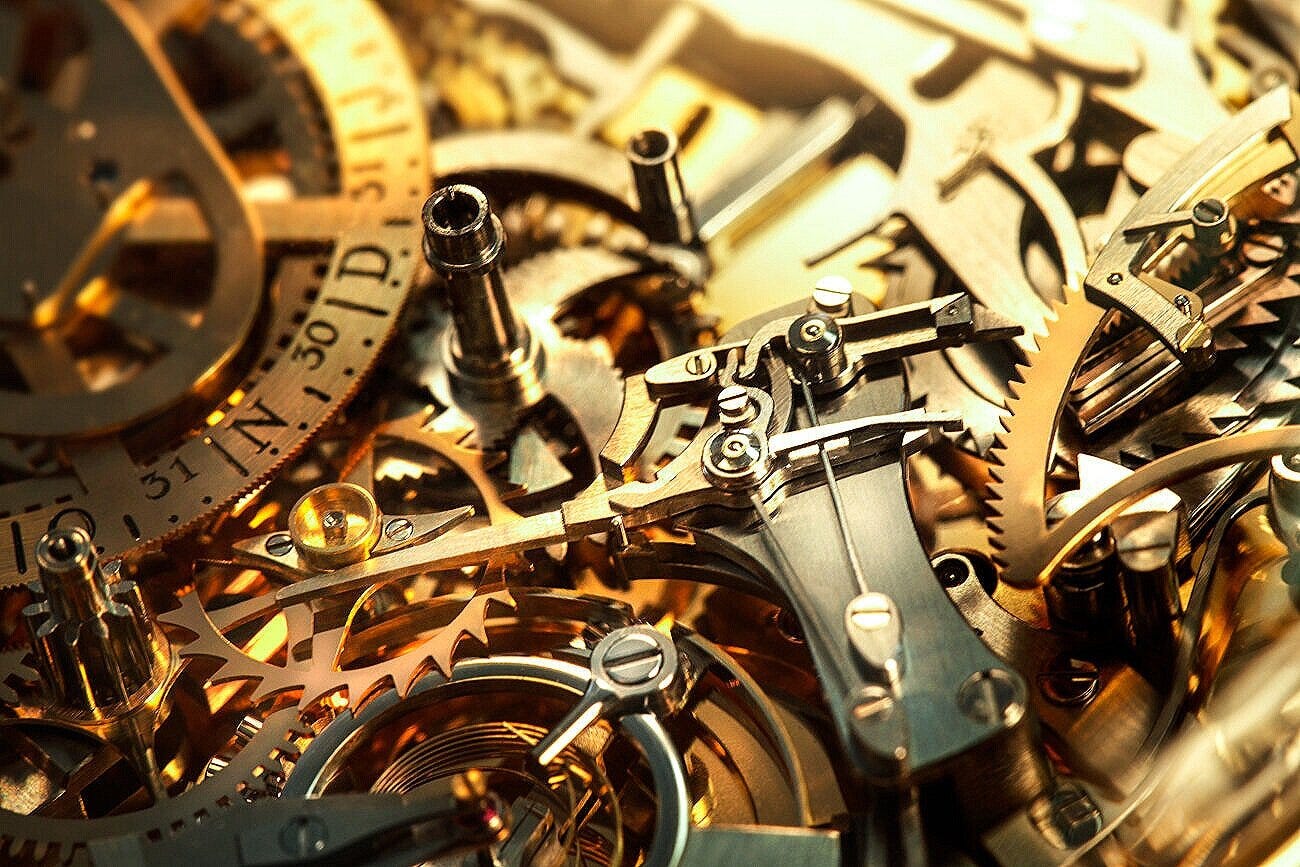

In the world of haute horlogerie, one might assume that nothing short of perfection would suffice. After all, we’re dealing with micro-mechanical marvels which adorn the wrists of discerning enthusiasts and tell time with astonishing precision1. Well, as we look under the hood, and into the process of creating a watch, we find even in this bastion of craftsmanship, the concept of the ‘80% solution’ has gained a troubling foothold2.

Consider, if you will, the creation of a new watch. A watchmaker could, theoretically, spend years perfecting every minute detail, polishing each component to a mirror finish, reworking the calibre to fit their vision exactly, and obsessing over the placement of every jewel. However, in today’s fast-paced market, many brands and watchmakers seem to be asking: is this level of dedication truly necessary?

The ‘80% solution’ in watchmaking recognises a point of diminishing returns. The difference between a movement that’s been finished to 80% perfection and one that’s been laboured over for an additional year to reach 99%, might be imperceptible to all but the most ardent watch nerds. More importantly, that extra year spent on a single calibre or design is a year in which nothing new is brought to market, no innovations are introduced, and sometimes, no revenue is generated.

This approach seems to make business sense. Take, for instance, the strategy of a brand like Rolex. While undoubtedly committed to quality, Rolex has built its empire on reliability, consistency, and incremental improvement rather than obsessive perfectionism3. Their movements are robust and accurate, their cases are well-constructed, and their designs are iconic. Are they the most ornately finished watches on the market? No. They are however more than good enough for their intended purpose, and this approach has allowed Rolex to continue dominating the luxury watch market.

The ‘80% solution’ frees up resources – both time and money – to invest in research and development or even just to boost profitability. It allows brands to iterate faster, to test new ideas in the market, and to respond to changing consumer preferences. In an industry that is steeped in tradition, this ability to innovate while ‘maintaining quality’ seems crucial.

Moreover, it allows brands to cater to a wider range of preferences. If they aren’t getting bogged down by perfectionism, they can offer a broader lineup of watches, experiment with different styles and complications, and ultimately, give collectors more choice.

Not to mention, if it’s that easy to create a watch, anyone can do it, right? Come up with a cool design, find an off-the-shelf calibre which nearly fits your design, make some small tweaks to accomodate the limitations, and boom! More choice, still. Surely, more choice is a good thing?

In embracing the ‘80% solution’, these brands ensure they are not just creating good watches, but doing so in a way that’s sustainable, innovative, and responsive to the market. In an industry that is all about keeping time, that’s a pretty valuable thing isn’t it.

Or is it?

The True Cost of Compromise

Fvck that.

Let’s be absolutely clear: the ‘80% solution’ has no place in the world of luxury. It’s a pernicious idea that’s slowly eroding the very foundations of what makes luxury watchmaking special. It’s time to call it out for what it is: a shameful capitulation to the pressures of profit over passion; Of quantity over quality.

The truth is, brilliant watches and outstanding design take time. They require 100% dedication, 100% of the time, because anything short of perfection is the antithesis of luxury. The idea that a luxury watch can be ‘80% perfect’ is an oxymoron; a contradiction in terms that betrays a fundamental misunderstanding of what luxury means.

Free subscribers will receive this post via email - 3 weeks after the date of publication. Sign up now to get it delivered to your inbox, or upgrade to paid and support future posts!

Two Ends of a Spectrum

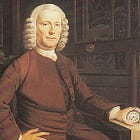

I’ve already told the story of Harrison’s pursuit of perfection (see footnotes), so how about a few others instead. Compromise often masquerades as practicality, but not when François-Paul Journe developed his Chronomètre Souverain. Here, he embodied the paradoxical pursuit of complex simplicity.

When designing the dial of the Chronomètre Souverain, Journe faced a conundrum that would have sent today’s watchmakers scurrying for the path of least resistance. Logic dictated that the power reserve indicator should be placed next to the crown at 3 o'clock – after all, what could be more intuitive than placing the fuel gauge next to the gas cap? The thing is, in the world of ultra-thin movements, logic is usually defied by physical constraints.

The placement of the power reserve indicator near the crown presented a problem: the basic construct of a typical power reserve mechanism simply wouldn’t fit above the crown without bloating the watch’s svelte profile. This was a puzzle that would have (and previously had) most watchmakers either relocating the indicator or allowing the case to be thicker. Not Journe. With his characteristic blend of genius and obstinacy, he saw this as a challenge, not a brick wall.

Instead of compromising his vision, Journe did what he does best: he innovated. He completely redesigned the power reserve mechanism, shrinking it down from a bulky 1.57mm to a wafer-thin 0.5mm through the use of ceramic ball bearings. The result was a power reserve indicator that not only fit perfectly where Journe believed it should be, but also improved the efficiency of the entire movement.

This episode in the creation of the Chronomètre Souverain perfectly encapsulates the philosophy I’m talking about - not to take the easy way out when the hard way leads to perfection. It’s a mindset which transforms a simple ‘dial design’ into a true testament to horological innovation. It turns what could have been a mundane design decision into a signature element of a masterpiece.

On the complete opposite end of the spectrum, let’s revisit a recently released watch: Furlan Marri’s Disco Volante. Their vision states:

“We are two friends united by a common passion for watchmaking who strive for perfection, accepting that we will never arrive.”

In stark contrast to Journe’s uncompromising pursuit of excellence and perfection, we find brands like Furlan Marri, whose approach to watchmaking is about as precise as a sundial in a dark cave. Here’s a company that claims to embody the spirit of fine watchmaking while seemingly confusing “hand-finished” with “finished by hand-waving at the general direction of Geneva.”

Their CHF2,500 offering, while admittedly sporting a slightly ‘fresh’ design aesthetic, is a masterclass in marketing over substance. The movement, allegedly decorated by hand, looks more like it was finished with a cheese grater than the careful hand of a master craftsman. This is the horological equivalent of finger painting being passed off as a Picasso.

The irony is palpable. In a watch whose primary appeal is its aesthetics, Furlan Marri chose to use a more expensive movement and an open case back. Why? It’s like putting a V12 engine in a golf cart and then putting a transparent cover on the engine as if it’s a good alternative to a Ferrari 812 GTS. It’s not, and it is also unnecessary, expensive, and frankly, a bit embarrassing. A closed case back and a simpler movement would have served their purposes just fine, allowing the brand to focus on what they are trying to sell.

How does this tie into their vision I shared above? That’s right, it doesn’t!

The problem is, this strategy works. Consumers, it seems, are all too willing to swallow the marketing pill, mistaking buzzwords for actual craftsmanship. Furlan Marri’s success is a testament not to their watchmaking prowess, but to their marketing acumen. They’ve mastered the art of premiumisation, and are now turning a brand previously known for cheap Patek Philippe copies into a “luxury” watchmaker.

This lazy approach to watchmaking, where marketing trumps mechanics and hype overshadows craftsmanship, is a serious cancer in the industry. It’s the antithesis of the perfectionism embodied by true masters. The truth is, as long as consumers continue to reward style over substance, we’re likely to see more of these horological hoaxes emerging from the woodwork.

The problem isn’t really with brands like Furlan Marri – it’s with us, the consumers. We’ve become so enamored with the idea of luxury that we’ve forgotten what true luxury means. It’s not about a price tag or a marketing story; it’s about the relentless pursuit of perfection, the kind of obsession that drives a watchmaker to redesign an entire mechanism just to place a power reserve indicator where it logically belongs.

If we don’t wise up soon, we risk turning the world of haute horlogerie into nothing more than a high-priced fashion show. The ticking heart of watchmaking – the innovation, the craftsmanship, the borderline insane dedication to perfection – is at risk of being silenced by the oppotunists selling mediocrity at a premium.

Something indeed must change, and fast. But that change needs to start with us, the watch enthusiasts and consumers. We need to demand more than just a pretty face and a good story. We need to celebrate and support the brands that embody true horological values, not just those with the flashiest Instagram presence and the best contacts in watch media. Only then can we hope to stem the tide of mediocrity threatening to swamp the shores of fine watchmaking.

Where to From Here?

Luxury is not about being ‘good enough’. It’s not about meeting a minimum standard or satisfying the majority of customers. Luxury is about the relentless pursuit of perfection, about creating something that transcends mere functionality to become a work of art. It’s about the hundreds of hours spent… Developing a calibre, prototyping and testing it, troubleshooting problems, hand-finishing the components, the painstaking attention to detail that ensures every facet of the case catches the light just so… the obsessive commitment to quality which ensures every single watch leaving the atelier is nothing short of extraordinary. You’ve heard the stories; watchmakers of old, painstakingly finishing parts which will never see the light of day, only due to pride in their own work. The mere knowledge that there was an unfinished area, even out of sight, was a burden too large to bear.

Another huge issue is the proliferation of ‘in-house’ movements that are anything but. Brands rush to claim the prestige of producing their own calibres, but how many of these movements truly represent any advancement in horology? How many have been subjected to the rigorous testing and refinement that characterised the great calibres of the past? Too often, these ‘in-house’ movements are merely reworked ebauches, rushed to market to satisfy a marketing checklist rather than to push the boundaries of watchmaking. Remember the Massena ‘in-house’ calibre I shared in May?

Another thing to consider is the trend towards ever-larger production numbers; True luxury is rare, yet we see so-called luxury brands churning out tens or even hundreds of thousands of watches each year. How can a watch be truly special, truly luxurious, when it’s produced on such a scale? The answer, of course, is that it can’t be. What we’re seeing is not luxury, but the illusion of luxury, a simulacrum that mimics the aesthetics of fine watchmaking without capturing its soul4.

The ‘80% solution’ is particularly insidious because it preys on the ignorance of consumers. Most watch buyers, even those spending significant sums, lack the expertise to distinguish between a truly exceptional watch and one that merely looks the part. They rely on brand names and marketing narratives, unaware that the watch on their wrist is a pale imitation of what it could – and should – be.

This is not to say that every watch needs to be a Henry Graves Jr. Supercomplication, or some other unicorn hand-crafted by a lone genius working in an attic. There’s room in the market for watches at various price points and levels of complexity. But even at the entry level of luxury, there should be an unwavering commitment to quality, a refusal to cut corners or accept ‘good enough’ because a horde of influencers seem to think it’s a good release.

The great watchmakers of the past understood this. They knew that their legacy would be built not on quarterly profits or market share, but on the enduring quality of their work. They created watches that have survived for decades, which continue to inspire awe and admiration long after their creators have passed away. Just look at the modern trend of reissuing old designs for proof of historical excellence. Can we say the same about the watches being produced today?

It’s time for the watch industry to reject the false promise of the ‘80% solution’. It’s time to recommit to the values that made watchmaking a true art form: patience, precision, and an uncompromising dedication to excellence. Anything less is not just a disservice to consumers, but a betrayal of the rich heritage of horology.

The next time you hear a brand boasting about their efficiency or their ability to bring new models to market quickly, be sceptical. Ask yourself: what corners have been cut? What compromises have been made?

In the world of true luxury, there’s no such thing as ‘80% perfect’. There’s only perfect.

The rest belongs in the bin.

Afterthoughts: This post was excessively inflammatory, and intended to spark a debate about the correct middle-ground between two extremes. Right now, we’re veering too far in one direction, and while we may never reach absolute perfection, I think some course-correction would be beneficial to the industry and to consumers.

Believe it or not, that “❤️ Like” button matters – it serves as a proxy to new visitors of this publication’s value. If you enjoyed this post, please let others know. Thanks for reading!

I’m being generous with 80% - sometimes it’s even less; But let’s stick with 80%,

This isn’t true, per se - they’re precisely as perfect as Rolex needs them to be, but stick with me for a moment.

Patek fanboys will have their arguments lined up. I’m waiting.

Well articulated and I tend to agree with most of what defines haute horology, innovation etc. and the overall thoughts being presented. While rarity and luxury can coexist and often do. I depart in scarcity being a requirement of luxury. The rare nature can be a by product of the other tenants mentioned in the article, even a constraint if you will by the process. But the constraints can be overcome and that would not change the nature of the products innovation, craftsmanship, artistry, etc… only its quantity. Status and value due to scarcity are correlated, but they are not attributes of luxury. That is a false attribute sold by advertisers and embraced by collectors because rarity can matter in collecting. Think of trading cards, a scare card in good condition is valuable to the collecting world, even selling for millions of dollars. It is not luxury, it has none of the hallmarks stated in the article of innovation, quality, craftsmanship or a pusuit of mastery and perfection. It is a cardboard card with an image printed on it, sold at a convenience store. It is rare, it commands a high price. It is not “haute” in any way.

The Calatrava 5227J from PP is a well made, finely finished, luxury watch. It is not however the same as the finishing and haute horology of the Chronometre Souverain Havana (my color of choice for CS) by F.P. Journe. The 5227J is also not the same haute horological art as a marquetry piece from PP’s rare handcrafts either. Both are Patek’s but they are not the same level. They have a different audience and convey a different level of craftsmanship and artistry. Innovation may not be present at typical 5227J but it is in the Fortissimo. We cannot look at a manufacturer with a catalog of 128 different models and say they are all the same. If the world of horology was filled with watchmakers who were all George Danniels and Francois-Paul Journe etc.. we would perhaps not recognize them. The genius, the true legends at the highest levels have dedicated themselves to their game, to their craft. We collect their works not because of the rarity of the work, but because of what it represents to us. The essence imbued in the watch. Be it the dedicate hands that crafted a dial that could hang in any gallery or the decorated movement that captures your attention as loose track of time while you gaze in admiration.

I am with you 97%. Rarity is a dangerous game to play, in absolute terms Patek is rare, any Patek is rare, making up only 0.002 of watches produced globally. With any particular model in the catalogue being 0.000017% of watches made annually. So in absolute terms they are rare. Rolex is a luxury watch so is Omega, they are not haute horology and they are vastly more common than a Patek or Lange or an. F.P Journe. But F.P Journe on the other hand is 90X more common and not rare compared to a Philippe Dufour in relative terms. That does not change the exquisite nature, the haute horology that you so aptly described of the F.P. Journe, especially the Chronometre Souverain Havana that needs to join the collection as some point and time.

I hope I have conveyed my thoughts correctly on this. This was a fantastic read, great food for thought. I will keep the hours spent writing and sorting my thoughts on this subject matter to myself. It was a great thought provoking article that had me personally exploring with many drafts and versions of how to better define luxury and haute horology. There are levels and tiers to luxury. So thank you for the thought provoking article that forced some deep thought and defining of items for myself. It only makes me a better collector and enthusiast when my thinking is refined.

Not sure how you argue this, but I'm going to think about it and the middle ground you mention. Simulacrum, that's a big boy word I've never encountered before. Cheers 🥂