The Rolex Story as told by Acquired

Part 1: 1881-1975

This has been in my workflow for far too long, and I must apologise for the delay! Given the podcast was 5 hours long, and that this post is far from being completed, I have decided to split the post into two parts.

This post is based on the following podcast episode:

Last year I shared deep dives into LVMH, Hermès and Porsche, based on the corresponding episodes of the Acquired Podcast. The response has always been fantastic, so I’m excited to bring you another brand breakdown from Acquired. I have previously done a podcast breakdown about Hans Wilsdorf (as a founder), and there are many overlaps in this post - so, fair warning, you may find the early years a little repetitive if you’ve already seen the previous post. This is of course different, because it focuses on the brand, rather than the founder (which was what the previous post was about).

Rolex seems to present paradoxes at every point in their existence. It is one of the world’s most recognised brands and yet, they operate with intelligence-agency-level secrecy. They make products everyone wants, but often, can’t get. They sell ca. 1 million watches each year, but at extremely high prices; something almost no other brand has managed to achieve. They seem to epitomise being at the pinnacle of mechanical precision (and innovation, to be fair), despite the fact that we’re in 2025, in a digital world, and what they actually sell is ‘obsolete’ in terms of utility1.

As with the previous deep dives, I’ll include quotes to add some colour. My guess is that this will provide about 80% of the story in roughly 10-15% of the time it would take to listen to the whole thing. All quotes are from the podcast, and all the sources are linked in image captions.

“Rolex is a cascade of paradoxes... one of the best-known brands in the world but despite that, it’s one of the least known companies in the world. They’re privately held by a charitable foundation, the Hans Wilsdorf Foundation, so they don’t have to disclose anything, and really, they never do. They’re one of the most secretive companies that we have ever studied.”

Prologue

There aren’t many brands that inspire as much admiration, intrigue, and, frankly, obsession, as Rolex. The iconic crown logo sits atop an empire worth “well over $100 billion”, though the exact figure remains a mystery due to their fanatical obsession with privacy. Unlike most luxury brands I can think of, Rolex isn’t publicly traded nor is it part of a larger conglomerate. Instead, it’s owned by the Hans Wilsdorf Foundation, a charitable trust established by the founder which exists to ensure they can operate with total independence and take an incredibly long-term outlook with all decisions.

Despite being the most widely coveted watch brand in the world, Rolex seems to defy all conventional ‘luxury logic’ if we can call it that. Actual luxury brands such as Hermès might make a few thousand Birkin bags a year, but Rolex produces over a million watches each year. Despite this, they maintain an air of exclusivity through a carefully managed distribution system which projects scarcity at the point of sale.

It’s quite remarkable how Rolex has built an empire selling mechanical watches given these represent an outdated technology which was rendered functionally obsolete by both quartz and smart watches. A £10 Casio will keep better time than a £9,000 Rolex Submariner, and still, the appeal of these anachronisms has only grown stronger over time.

How did Rolex transform obsolescence into triumph?

“This is a story of the most successful Swiss watch company, but it wasn’t founded in Switzerland or even by a Swiss person. It’s a 10+ billion-dollar revenue business performing a dead craft obsoleted by the digital world. They make a watch that can’t tell the time as well as my Apple Watch or even a $10 Casio. So, what is going on here? How did Rolex become Rolex?”

Side note:

What’s very surprising to me about this Acquired episode is how little attention was paid to what I think is one of the most valuable aspects of their business model - Rolex’s extraordinary property portfolio and accumulated assets. Given how deep this podcast usually goes, I expected to find a little more detail on Rolex’s real estate empire, but it seems even the Acquired nerds could barely scratch the surface. They basically gloss over it:

“They own some of the most expensive real estate in the world. They own their own buildings in Switzerland, they own in the Bond Street house area in London some really, really prime real estate, in Milan, in Melbourne, in Tokyo, famously in New York City there’s a gorgeous building that they’re building about a block from Rockefeller Center and Radio City Music Hall... They own a building in Manhattan... They own a lot of real estate in Geneva, they own a big service center in Dallas, the school in Pennsylvania. Hilariously they just bought the building where Omega has their flagship store in Geneva, so Omega makes a rent check out to Rolex every month.”

Despite not knowing the size, what is worth understanding is that these real estate investments provide Rolex with stable, long-term returns from prime locations which also tend to appreciate over time. Real estate is also quite a prudent way to deploy the enormous cash reserves generated each year - $3-4bn p.a - and total accumulated assets estimated at well over $50 billion by the Acquired podcast.

Official figures are closely guarded, but many industry observers believe returns from these property investments now form a substantial portion of the foundation’s overall profitability. The Hans Wilsdorf Foundation has effectively created a virtuous circle where the watch business generates huge cash flow, this is invested in premium real estate, which in turn provides additional returns and stability, and this further strengthens the foundation’s ability to operate the watch business with a super-long-term perspective.

I guess the property empire is just another paradox in the Rolex story, in that a company known for making watches exceptionally well appears to derive significant financial strength from an entirely different business altogether!

Anyway, tangent over. To understand Rolex’s success story, we must journey back to the late 19th century and meet a young orphan whose vision would ultimately transform both watchmaking, and the very concept of luxury itself.

Foundations of a Dynasty (1881-1905)

This tale begins on March 22, 1881, in Kulmbach, Bavaria, with the birth of Hans Otto Wilhelm Wilsdorf. He was born to a family of innkeepers, and young Hans would face tragedy early in life when both his parents died within months of each other – this left him an orphan at just 12 years old.

Astute readers will realise how, Hans’s early hardship actually created a random coincidence which links three of luxury’s greatest names:

“Louis Vuitton and Thierry Hermès… the founders of arguably maybe the three biggest and most significant luxury brands in the world today were all orphans from the 1800s.”

Hans was placed under the care of his maternal uncles, and they sent him to boarding school where he excelled academically - particularly in mathematics and foreign languages (this becomes important later on). His uncles sold the family business to fund his education, and this was a decision which Hans would later credit as being quite formative:

“Our uncles were not indifferent to our fate. Nevertheless, the way in which they made me become self-reliant very early in life made me acquire the habit of looking after my possessions, and looking back I believe that it is to this that much of my success is due.”

--

Before we go on, it’s worth talking a bit about Switzerland’s rise as the watchmaking capital of the world, and how it has historical roots dating back to the 1500s. Geneva had become a centre for Protestant Christians led by John Calvin, whose moral code banned frivolous ornamental jewellery. Local goldsmiths and jewellers therefore pivoted to watchmaking, since watches served a practical function rather than mere adornment.

Switzerland’s climate played a crucial role too - long, harsh winters made indoor crafts with small footprints ideal. The region developed a unique economic system called “établissage,” where tiny independent companies specialised in making single components, and dozens of them collaborated to create finished watches (I wrote about this a while ago). As a result of this distributed manufacturing system, incredible specialisation and craftsmanship was possible because everyone was a jack of no trades but a master of one!

The influx of French Huguenot refugees (who brought watchmaking expertise when Catholics came to power in France) also ended up strengthening Switzerland’s watchmaking foundation. All of these circumstances created a blend of French aesthetic appreciation and Swiss precision that would come to define the industry for a long time.

--

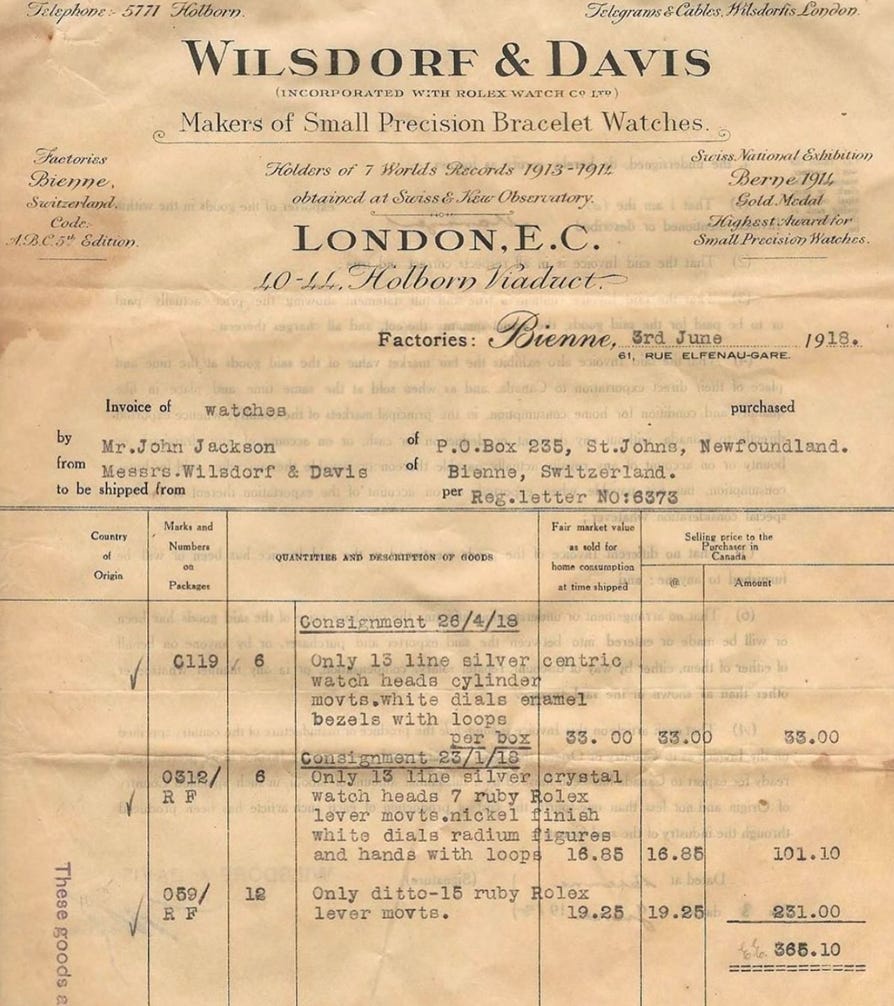

Anyway, after completing his education and brief military service, Wilsdorf moved to Switzerland, supposedly sold on its reputation and a Swiss friend he’d met at school. In Geneva, he first found work with a pearl merchant before joining a watch export company called Cuno Korten, which was a major player that did about a million Swiss Francs of business annually.

This position was super-pivotal for Wilsdorf’s future. Firstly, as a secretary handling correspondence for English-speaking clients, he gained intimate knowledge of both the watch production ecosystem in Switzerland and the retail distribution network in Britain. Next, he also developed a passion for the products themselves; he would often take batches of pocket watches home to test their accuracy overnight.

In one experiment, Wilsdorf took the best-performing watches from his personal testing to the local astronomical observatory for official chronometer certification. These ‘certified’ watches sold extremely well, which gave Wilsdorf his first insight into how technical achievements could be translated into marketing advantages.

In 1903, at age 22, Wilsdorf moved to London to work for another watch company where he got further experience in the British market. Two years later, feeling confident in his understanding of both the technical and commercial aspects of the business, the 24-year-old decided to do his own thing.

The problem was, he needed capital!

Through his lawyer, Wilsdorf connected with Alfred James Davis; some rich guy who had funds to invest. The two hit it off immediately and formed Wilsdorf & Davis Limited in 1905. While Davis would later become Wilsdorf’s brother-in-law by marrying his sister Anna, the business was truly Hans’s creation, with Davis primarily providing financial backing.

The business model was simple; they’d import high-quality Swiss movements and cases, assemble them in London, and sell the finished watches to retailers across Britain. At the time, most watches did not have the manufacturer’s name on the dial - retailers would place their own name on the dial and take credit for the product. This arrangement annoyed young Wilsdorf because he believed his watches deserved their own identity.

Innovation in Born (1905-1920)

From the outset, Wilsdorf showed a keen sense for differentiation in the market. Instead of competing broadly across the entire watch market, he focused on what he called “speciality horological products” - particularly portable watches cased in fine leather, which allowed for higher margins and reduced direct competition.

It turned out, Wilsdorf had a more radical vision brewing. While he was reading an account of the Boer War in South Africa, he noted soldiers had worn wristwatches to coordinate their movements because they could keep their hands free for battle. Also at the time, wristwatches were considered feminine accessories - called “wristlets” - and weren’t taken seriously as timekeeping instruments for men (who still carried pocket watches).

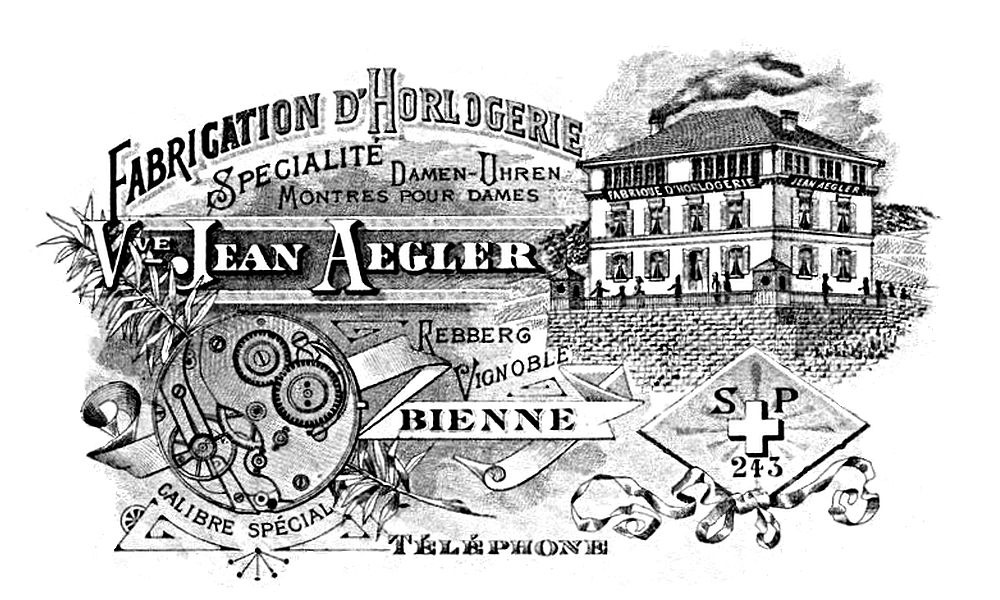

Naturally, he sensed an opportunity; Wilsdorf contacted Jean Aegler, a Swiss movement maker based in Bienne who specialised in small, precise movements. Aegler was something of a hidden gem in the industry because they could produce movements on par with the best in Switzerland - but they were focused on miniaturisation before there was substantial market demand. Wilsdorf placed an order for several hundred of these small movements. This was the start of a partnership that would last for nearly a century.

Even though Wilsdorf’s instincts about wristwatches would eventually prove correct, the market wasn’t quite ready yet. It would take another decade - and a world war - before wrist watches would be widely adopted by men. In the meantime, Wilsdorf had another revolutionary idea.

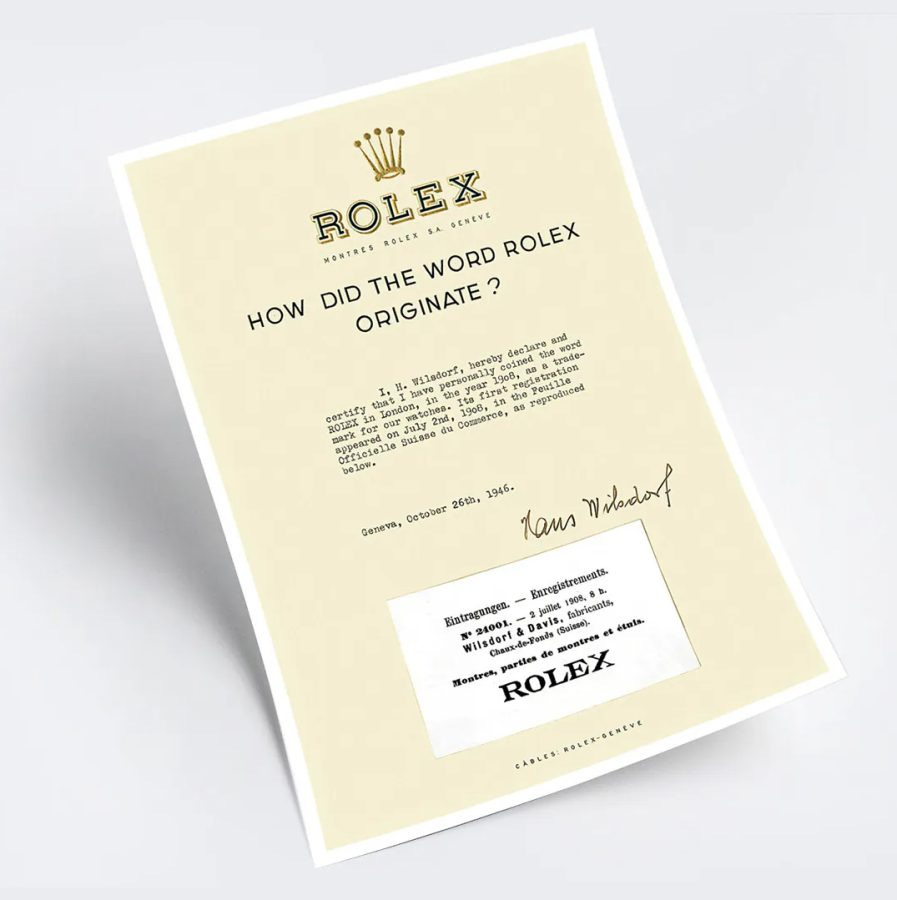

If he was going to build a brand around wristwatches, he needed a memorable, distinctive name. Inspired by Eastman Kodak - one of the first invented-product brand names - Wilsdorf needed a name which was short, easy to pronounce in any language, and memorable.

“I tried combining the letters of the alphabet in every possible way. This gave me some hundred names, but none of them felt quite right. One morning, while riding on the upper deck of a horse-drawn omnibus along Cheapside in the City of London, a genie whispered ‘Rolex’ in my ear.””

Who knows… this could easily be some post-hoc myth making, but the name Rolex proved to be a masterstroke. Short, distinctive, and maybe a little suggestive of the rotation of watch hands; either way, it was registered as a trademark in 1908. Initially, this was just used as a brand name for products from Wilsdorf & Davis (i.e. it wasn’t the company name).

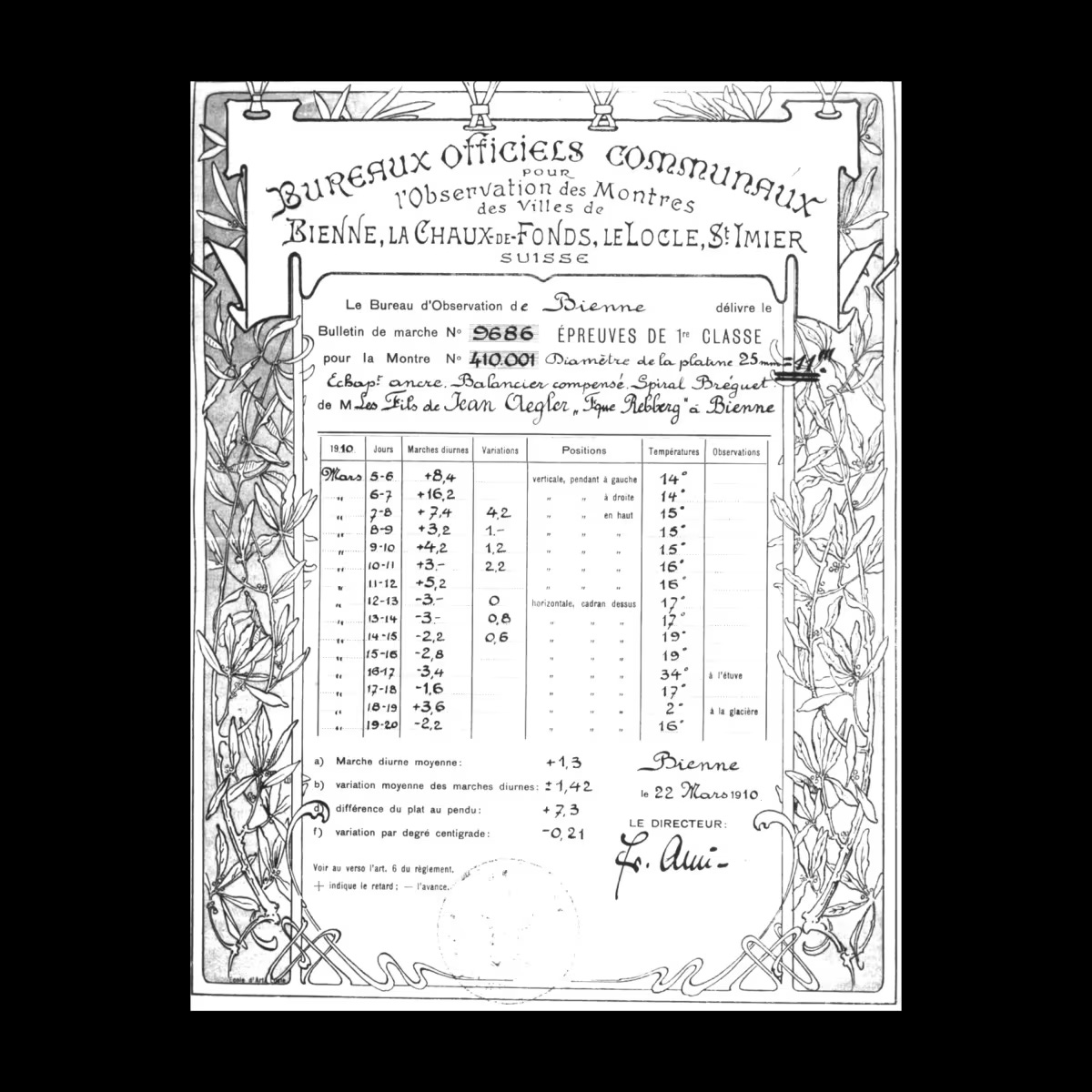

But our man Wilsdorf still wasn’t fully satisfied. A good name and quality products were cool, but he also understood the importance of third-party validation - especially for a new brand trying to overcome scepticism about wristwatches. In 1910, a Rolex became the first to receive chronometer certificationfrom the Official Watch Rating Centre in Bienne - not bad, but still not the highest recognition available.

The ultimate prize remaining was certification from the Kew Observatory near London, which tested the British Royal Navy’s marine chronometers. After years of refinement with Aegler, Wilsdorf submitted a Rolex wristwatch for the rigorous 45-day Kew trials. On July 15, 1914, this watch received the first-ever Class A Precision certificate ever awarded to a wristwatch, which essentially proved that a properly engineered wristwatch could be as accurate as a pocket watch.

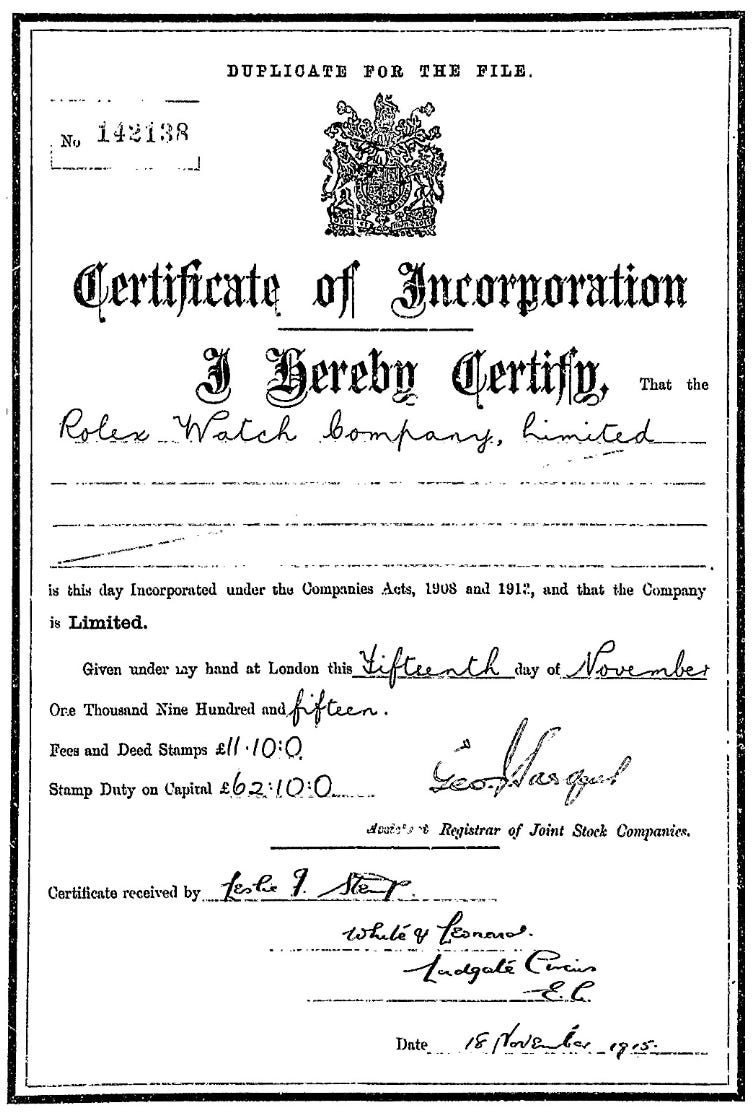

Unfortunately, this event was overshadowed by the outbreak of World War I just a few weeks later. As anti-German sentiment spread across Britain, Wilsdorf’s German name became a liability - despite his British citizenship and distance from his German roots. In 1915, Wilsdorf & Davis rebranded to become The Rolex Watch Company.

The war also created other challenges; Britain imposed a 33% import tax on watches and later completely banned the import of gold and silver – which were critical materials for luxury watches. These restrictions, along with the general wartime disruption, made Wilsdorf relocate to (neutral) Switzerland. First he established assembly operations in Bienne (near Aegler) in 1916, and then he moved their headquarters to Geneva in 1919.

As it happens, this move to Switzerland proved fortuitous in ways Wilsdorf couldn’t even have anticipated. Switzerland’s neutrality ended up protecting Rolex through both World Wars, and on top of that, allowed them to continuously produce their watches while competitors in belligerent nations were forced to convert their factories to military production. Score.

Before we go on, a couple short footnotes from WWII history are in order. First, Rolex supplied watches to the Italian Navy through Panerai. When the Italian retail partner secured a contract for dive watches for their military, they approached Rolex, who agreed to make them despite the wartime constraints.

Another cool anecdote is that during WWII, Rolex offered watches to British prisoners of war in German camps - to be paid for after the war. Hans Wilsdorf was apparently so confident in an Allied victory, he is claimed to have said: “You have enough things to worry about. The last thing you should worry about is your bill with me.” Of course, this gesture of goodwill and faith - if true - would say a lot about Wilsdorf’s personal values, and seems to have built a ton of goodwill for the brand with military officers.

Perfecting the Watch (1920-1945)

So he’d gotten his watches certified as chronometers, and having established a foothold in Switzerland, Wilsdorf now faced the challenge of turning his vision for wristwatches into reality. World War I had done a lot to popularise wristwatches among men, because soldiers had discovered their practicality in combat. As veterans returned to civilian life, many of them continued to wear wristwatches which caused public perception to gradually shift in favour of regular men (non-soldiers) wearing them too.