Why Watch Collectors Talk Past Each Other

Or anyone, really. Five questions hiding inside "why did you buy that?"

There’s a specific type of online argument which will never be resolved. Someone posts a photo of a new purchase, say, a Cartier Santos. Within about 30 comments, several separate debates will be taking place concurrently.

One person is explaining that the Santos makes no sense because the resale value is poor compared to a Rolex. Another person is arguing that Cartier’s heritage in the Santos design purportedly predates almost everything else in modern watchmaking, so of course it makes sense. A third person is saying they’d never buy it because they tried one on and it just didn’t feel right on the wrist.

Clearly, these people aren’t even disagreeing with each other, they’re just answering different questions.

Estimated reading time: ~14 minutes

Another framework

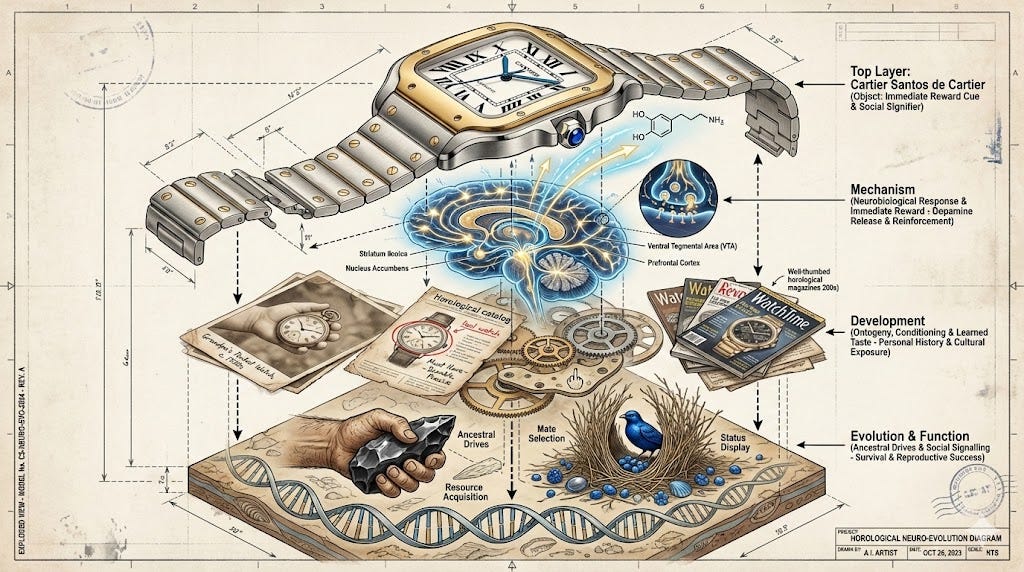

Today we will explore a 1963 paper by Nikolaas Tinbergen - a Dutch ethologist who would go on to win the Nobel Prize for his work on animal behaviour. Tinbergen noticed that scientists studying animal behaviour kept talking past each other because they were using the word why to mean completely different things. His framework for sorting this out1 turns out to be incredibly interesting when applied to watch collecting - and particularly good for understanding why collectors who seem perfectly intelligent can look at the same purchase and reach opposite conclusions.

Now, at the time, Tinbergen didn’t set out to create some sort of “universal theory of explanation” or anything; he was just trying to get his colleagues to stop arguing about things he saw they actually agreed on. Still, what he ended up with was a neat map of the different questions hiding inside “why did you do that?”

When someone asks why you bought a particular watch, they might be asking about your intentions (what were you trying to achieve?), or about your history as a collector (how did you end up valuing this type of thing?), or about what the behaviour accomplishes in some deeper sense (what is collecting even for?), or about how human beings ended up being the kind of creatures who collect things at all, or even about what was happening in your brain at the moment of purchase.

In fact, subconsciously, they may even be asking more than one of these questions at the same time, and your response will remind them about what remained unanswered (but post-fact). And sure, these are all valid questions, and some might even be interesting questions - but they have completely different answers.

Intent matters

I’ll start with the most obvious one, because this is the question people usually think they’re asking - it is about your intentions.

“I bought the Santos because I wanted something elegant that I could wear with a suit but also looked good with casual attire. I’ve always admired Cartier’s design language, and the price was right given my budget.”

This seems to be a perfectly reasonable answer. It explains your goals, your reasoning, your conscious decision-making process, and even your constraints. If you’re having a conversation with a friend about your new watch, this probably covers everything they might want to know.

Now, did you notice how this answer is silent on a bunch of other questions? It doesn’t explain why you have the aesthetic preferences you have. It doesn’t explain why humans collect things. It doesn’t explain what was happening neurologically when you handed over your credit card. It doesn’t explain why you didn’t just buy a Rolex, since Lotus will say you’re a moron for not doing so. Those are all different questions… valid, but different.

The thing about intentions is that they’re the one type of explanation that only works for the beings that actually have them. You can ask why I bought a Santos; you can’t meaningfully ask why the secondary market crashed in 2022 using intention-why, because markets don’t have intentions (some people talk as though they do, but that’s a different problem!).

Tinbergen actually excluded intentions from his original framework because he was studying animals and didn’t want to anthropomorphise2. Anyway, we’re discussing watch collectors, who definitely do have intentions - sometimes confused intentions, sometimes conflicting intentions, and oftentimes dumb intentions… but yeah, intentions nonetheless.

How did you get this way?

This all gets even more interesting when you think about the underlying developmental question - which is something like “how did you become the kind of person who would make this purchase?”

At first you might think wtf, that’s too deep - but it’s really not. Perhaps you grew up around someone who appreciated good design. Or maybe your first ‘real’ watch was a gift that steered your future taste. Maybe you spent years on forums absorbing particular aesthetic values or characteristics in a watch such as value retention. Or you may have had some formative experience - a trip to Geneva with a watch-nerd parent, a conversation with an inspiring watchmaker, or any similar moment when a penny dropped in your head.

The developmental answer to “why did you buy the Santos?” might be something like “I spent my early collecting years obsessed with tool watches, but after a decade of that, I started noticing that what I actually reached for most often were thinner, more elegant pieces. The Santos represents where my taste has evolved to after 15 years of handling watches.”

This is a completely different type of answer than the intention answer from earlier. The intention answer is about your conscious goals at the moment of purchase. The developmental answer is about the long process that shaped those goals in the first place.

And yes, you might not even be aware of your developmental history. You might think you ‘naturally’ prefer elegant watches, without recognising all the experiences and exposures which created that preference. Some of the most interesting developmental explanations are probably ones you don’t know yourself - or at least, haven’t given much thought to.

Morgan Housel makes a similar point in his new book The Art of Spending Money3. There’s a saying inside the foster care system - “All behaviour makes sense with enough information.” Once you understand what someone has dealt with in their life (be it uncertainty, formative experiences, little things which shaped their values) their behaviour begins to make sense. Housel talks about how this applies directly to the way in which people spend money; he says your spending habits reflect the social and psychological experiences of your life. Since those experiences vary dramatically from person to person, what makes sense to you might seem crazy to me, and vice versa.

A collector who grew up watching their father admire dress watches at a local retailer has a completely different developmental path to someone who discovered watches through seeing James Bond wearing a Rolex (or Omega) or Martin Sheen wearing a Seiko in Apocalypse Now! None of these is right or wrong… they just got here using different routes.

Wtf is happening inside your head?

This part is about the mechanism or what Tinbergen called “causation.”

When you walked into that boutique and tried on the Santos, something happened in your nervous system. Visual information was processed, reward circuits were activated (or not), memories were triggered, anticipation systems fired, and the physical sensation of the watch on your wrist was finally integrated into your existing expectations and preferences. It’s a lot of parallel processing, as you can imagine… and then, at some point during this parallel processing, you became committed to the purchase.

What actually happened in that moment?