The Wolf in Cashmere: How Bernard Arnault Built LVMH into the World's Largest Luxury Empire

Discovering the Visionary Strategies, Bold Acquisitions, and Unparalleled Brand Power Behind the Rise of a Global Powerhouse

A few weeks ago Eric Ku shared a podcast link in a collector chat, and another collector quipped: “4hr podcast, that’s like a part-time job!” I happen to enjoy podcasts, and the Acquired Podcast is one of the better ones out there. Here’s a great article about the podcast itself, which will shed some light on just how good it is.

Many people prefer long-form written content to audio, so I thought it would be fun to switch gears from strictly horological topics and dive deep into the world of luxury.

So… today I will break down a behemoth episode of the Acquired podcast about LVMH. I will include quotes from the podcast, and try to talk you through the key points in the story. This is not a substitute for the podcast - but I’d like to think you’ll get at least 80% of the story with 20% of the time invested!

Hope you enjoy it - the estimated reading time is between 24 and 30 minutes, according to a few online calculators… hope that helps with your planning 😊

Prologue

Few empires loom as large as LVMH; a French luxury conglomerate that owns some of the most iconic brands on the planet, from Louis Vuitton to Dior to Hennessy. With over 75 “maisons” under its umbrella and a market cap that has climbed 20x in 20 years… LVMH is indeed a powerhouse.

Side note: Moët is pronounced MO-ET with a hard ‘T’ and not MO-AY as you often hear people saying - the word is not of French origin, but Dutch.

“LVMH is the 15th largest company in the world today by market cap. It is the only company in that top 15 that is not technology or oil besides Berkshire Hathaway.”

Arnault’s story is one for the ages. How did this son of a French industrialist go from running a small construction firm to becoming the richest man in the world, with a personal fortune of over $200 billion? The answer lies in a combination of vision, timing, ruthless deal-making, and an unparalleled understanding of brand power.

LVMH is undeniably a case study on brand power - the elusive quality that can make people pay vastly more for a product just because it has a certain logo on it.

The Dior Revolution

Our story begins not with Arnault, but with another legendary figure in the history of luxury: Christian Dior. The year was 1946 and the world was still reeling from the devastation of World War II. In the fashion capital of Paris, the mood was sombre - women were still dressing in the boxy, masculine styles imposed by wartime austerity.

“Paris in 1946, it’s not quite as bad as Tokyo in 1946, but this is not a happy place. France and Paris, of course, had been occupied during most of the war by the Nazis. Although the economy wasn’t totally destroyed like in Japan, it was pretty much entirely shifted during the war to supporting the Nazi war effort.”

Enter Dior, a 41-year-old designer working for an old Parisian fashion house. With the backing of textile magnate Marcel Boussac, Dior struck out on his own, determined to bring a new silhouette to women’s fashion. His first collection, unveiled in 1947, was a brazen rejection of the utilitarian wartime aesthetic in favour of a feminine, luxurious “New Look” featuring cinched waists, soft shoulders and long, full skirts.

“Nazi ideology abhorred Parisian styles and the slender feminine bodies it idealized, arguing that they were both corruptive to natural strong Aryan women. Instead, Adolf Hitler advocated for the practicality and nationalist quality of German dress, which saw women in drab and boxy uniforms.”

It was a sensation. Women swooned over Dior’s lavish designs, which used yards and yards of expensive fabric. Men grumbled about the costs (one group, the “League of Broken Husbands”, even staged protests). But there was no denying Dior had sparked a fashion revolution. By 1949, his brand accounted for a whopping 5% of France’s total export revenue.

“Two years later, by 1949, Dior fashions were literally 75% of Paris’s fashion exports and 5% of the entire nation’s export revenue. I believe to this day; the luxury industry is the largest export of France.”

ScrewDownCrown is a reader-supported guide to the world of watch collecting, behavioural psychology, & other first world problems.

Enter… Yves Saint Laurent

Dior’s time at the top was tragically short-lived. In 1957, at the height of his fame and just after appearing on the cover of Time magazine, the designer died of a sudden heart attack. The question on everyone’s mind: what would become of his brand?

“Suddenly, right after that later, in 1957, at the height of his international cultural popularity, he dies suddenly of a heart attack, very unexpectedly. This is a huge deal. It’d be a huge deal today if the creative leader of a major fashion house died unexpectedly as happened sadly, often.”

The answer came in the unlikely form of Yves Saint Laurent, Dior’s 21-year-old head assistant. In a controversial move, Saint Laurent was named artistic director of the House of Dior and set about reinventing its signature style for a new era. Over the next few years, he pioneered a strikingly modern look characterised by slim, chic silhouettes like the iconic Mondrian dress.

While Saint Laurent’s designs were a hit with younger women, they were too radical a departure for Dior’s old-guard management. In 1960, he was unceremoniously fired (he would, of course, go on to start his own legendary brand). Without Saint Laurent’s creative genius, Dior entered a period of slow decline, coasting on the fumes of licensing deals which, over time, cheapened its once-exclusive aura.

“They basically never recover from this. Boussac installs the conservative and older Marc Bohan as artistic director. The innovation is gone. They basically just keep pumping out variations of the new look for the next 10–20 years.”

Boussac Goes Bust

Behind the scenes, all was not well with Dior’s parent company. Marcel Boussac’s textile conglomerate had ballooned into an unwieldy empire spanning not just fashion houses but also various manufacturing businesses employing some 20,000 unionised workers. It was losing money hand over fist.

“It’s mostly a textile manufacturing business. They’re 20,000 employees. It’s all unionized. France is basically becoming a socialist country. It gets to a point where, by the late 60s, they’re losing $20 million a year across the whole company.”

Boussac tried to stop the bleeding by selling off assets, including Dior’s lucrative perfume division (which was scooped up by Moët & Chandon champagne house in 1968 – this will be important later). But it was too little, too late. By 1978, Boussac was bankrupt, leaving Dior and its sister brand, the famed Parisian department store Le Bon Marche, in the hands of the French government!

“In 1978, the whole Boussac group finally files for bankruptcy in (up into this point) the largest bankruptcy in French national history. This is a big deal.”

The Arnault Era Begins

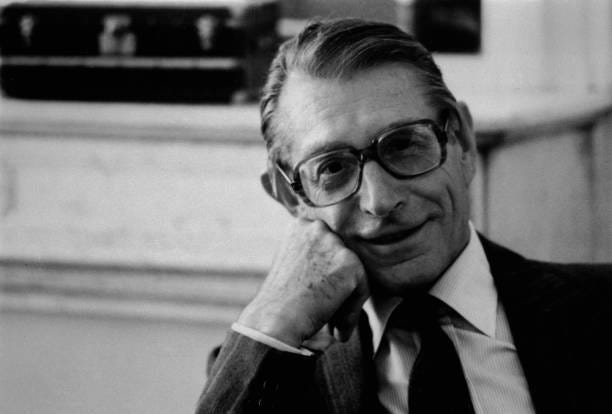

Enter Bernard Arnault, then a young French businessman who had been steadily building up his family’s construction company. Arnault had recently spent time in the U.S. where he became enamoured with the concept of the LBO (leveraged buyout)1. He saw an opportunity in Boussac’s crumbling empire.

“When you live in a country and do business in it for some time, you try to be influenced by it, especially when you do business in the paradise of business, which is America.”

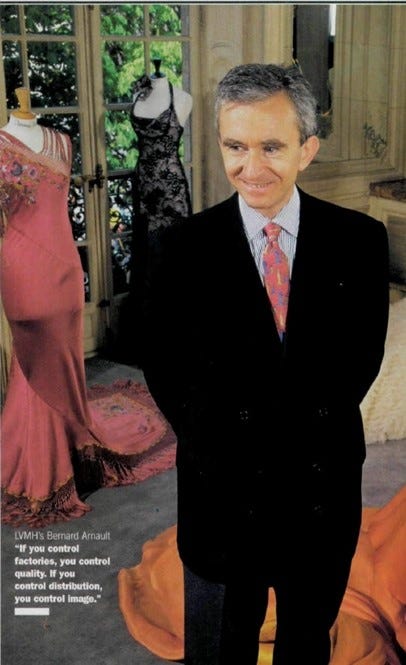

In 1984, Arnault teamed up with the investment bank Lazard Freres to launch a daring takeover of Boussac. The price tag? $60 million… and just $15 million of which was Arnault’s own money; a bet that would pay off spectacularly.

“The Arnault family puts up $15 million. Lazard goes out and rounds up investors and I think invest some of their own balance sheet into this for the other $45 million.”

Arnault – just 35 years old at the time - quickly set to work restructuring Boussac with ruthless efficiency. He laid off 9,000 workers, sold off various textile businesses and manufacturing units, and zeroed in on the crown jewel buried within the company: Dior. The French press called him The Terminator. By refocusing the brand on its core competency in luxury fashion and accessories, Arnault believed he could revive its faded prestige.

“Some people say I’m a wolf. That is not at all true. Wolves break up companies into pieces. It was Racamier who wanted to cut the company into pieces. I was the only one who did not want to dismantle it.”

He was right. Arnault’s strategy, combined with Dior’s resilient brand equity, worked wonders. Within a few years, Dior was solidly profitable again and Arnault’s initial $15 million investment had ballooned into a stake worth hundreds of millions of dollars. The wolf of French luxury had scored his first major kill2.

“Within a couple of years, the Boussac businesses as a whole, the empire, is doing about $2 billion in revenue, and it’s back to profitability. It’s doing over $100 million in profit and then he turns it around.”

The Making of a Mega-Merger

Arnault’s next move would be even bolder. But before we dive into the transformative merger of 1987, let’s take a step back and explore the history of the two legendary companies that would come together to form the nucleus of LVMH: Moët Hennessy and Louis Vuitton.

The story of Moët Hennessy begins, appropriately enough, with a marriage. In 1971, two of France’s most storied booze producers, Moët & Chandon and Hennessy, joined forces. The architect of the deal was Alain Chevalier, a visionary executive who saw the potential for synergies between the two companies.

By combining Moët’s dominance in champagne with Hennessy’s global leadership in cognac, Chevalier believed he could create a distribution powerhouse with unrivalled scale and influence. He was right. Over the next decade, Moët Hennessy’s revenue grew from around 300 million francs to well over a billion, as the combined company made aggressive moves into new markets like the United States and Japan.

Meanwhile, another dynasty was taking shape at Louis Vuitton under the leadership of Henry Racamier, a charismatic manager who had married into the Vuitton family. When Racamier took the reins in the late 1970s, Louis Vuitton was a prestigious but stagnant brand, with just two stores to its name and annual revenue of around $12 million.

“What he did is frankly amazing. I don’t think it’s an overstatement to say that Henri Racamier invented the modern global luxury brand.”

Racamier had a bold vision to transform Vuitton into a global juggernaut. He opened new stores, pioneered the concept of the flagship retail emporium, and began expanding into new product categories beyond the company’s traditional stronghold in luggage and leather goods.

By 1984, his strategy had paid off. Louis Vuitton was now generating $143 million in sales from 15 stores worldwide, and Racamier made the decision to take the company public on the Paris Bourse. It was a coming-out party for the brand, and a sign of the increasing power and prestige of the luxury sector.

Still, even as Moët Hennessy and Louis Vuitton were riding high, trouble was brewing behind the scenes. In the freewheeling 1980s, a new breed of corporate raiders and hostile takeover artists was on the rise, and many of France’s most iconic companies were becoming juicy targets.

“This merger between Moët and Hennessy made a ton of sense and was super successful. It happened in 1971. It was led from the Moët side by this pioneering guy, Alain Chevalier, and he was the first nonfamily, outside manager of Moët & Chandon and any of these old family brands.”

Desperate to ward off the barbarians at the gate3, Racamier and Chevalier began to explore a defensive merger of their own. In 1987, they announced with great fanfare that Louis Vuitton and Moët Hennessy would join forces, creating a new luxury conglomerate with the catchy acronym LVMH4.

“It was not because that was the goal. This is a marriage of convenience. This is not some grand strategy. The reason it happens is they’re trying to prevent takeover attempts from corporate raiders. All these Americans and American-style businesses come in to raid these old French companies.”

But even from the start, it was an uneasy alliance. Racamier had grand ambitions to make Louis Vuitton the dominant force within the group, while Chevalier and the Moët Hennessy old guard were wary of the brash upstart. As chairman of the newly formed LVMH, Chevalier made sure to keep Racamier on a tight leash.

Tensions came to a head when Chevalier asked his friend - Guinness’ CEO Anthony Tennant - to buy LVMH shares to prevent a hostile takeover. Racamier was aghast at the idea, noting this would become a booze-driven business, wen if fact he saw is own brad, LV, as the actual crown jewel.

At this point, Racamier goes to Arnault, and urges him to help take a stake - primarily to help him create a defensive position for the company - not realising, what he was about to unleash. Anyway, Arnault presents as a hero who could help Racamier fend off the advances of Chevalier and Guinness.

Behind the scenes, Arnault was playing a different game. He had already thrown in his lot with Chevalier and Guinness because Lazard, who was the banker for both Arnault and Guinness had introduced them secretly. Arnault now saw Racamier as the real obstacle to his grand vision for LVMH. Still, around this point even Chevalier realises what is going on… By allowing Arnault and Guinness to align, they had let the fox into the henhouse!

With the help of Guinness, and despite the best efforts of Racamier and Chevalier, Arnault seized control of the company, snatching control from both Racamier and Chevalier!

The rest, as they say, is history. With LVMH as his vehicle, Arnault would go on to assemble an unrivalled portfolio of luxury brands, from Christian Dior to Sephora to Bulgari… But really… it all began with the merger in 1987.

“Once this happens and Bernard gets the blocking minority, Chevalier resigns immediately and just rides off into the sunset. Racamier, he’s so pissed. He keeps fighting. He sues Bernard, he sues everybody. The case is drag out in court for a couple of years, it gets super ugly in the press… Finally, when it becomes clear that he’s not going to win his court cases in April of 1990, he privately resigns, and [Racamier] walks off the job without telling Bernard or anybody else at LVMH.”

Cleaning House and Ruffling Feathers

Arnault wasted no time shaking up LVMH’s culture. He quickly set about applying the same cost-cutting measures and brand-centric strategies he had used to turn around Dior.

It was a period of rapid expansion and acquisition for LVMH, with Arnault snapping up majority stakes in a slew of premium brands like Celine, Kenzo, and Berluti. He also made big investments in retail, acquiring beauty chain Sephora and travel retailer DFS (the company behind all those duty-free luxury shops in airports).

Crucially, Arnault realized that LVMH could wield enormous clout with department stores and other third-party retailers by virtue of its now-sprawling collection of brands. No longer would the likes of Saks and Neiman Marcus call the shots - LVMH effectively invented the “store-within-a-store” concept, insisting on controlling its own inventory, sales staff and visual merchandising within retailers’ walls. This is vertical integration at its best - the ‘big stores’ were now glorified landlords in their own shops.

“The old model, where we sold you our goods wholesale, you bought it from us, and then you retail them, we’re not going to do that anymore. We are going to retail our own products within your stores. This is the store within the store concept.”

It was a masterful power play, one that allowed LVMH to command higher margins while tightening its grip on the customer experience. Thanks to the combined scale of its brands, LVMH could now negotiate better lease terms on prime real estate and strike huge advertising deals to keep growing its all-important brand equity. The virtuous cycle of a luxury conglomerate was starting to kick into gear.

Gucci and Goliath

For all his successes in the ‘90s, there was one which Arnault failed to bag: Gucci. The Italian luxury brand had a long and storied history, but by the early 1990s, it had fallen on hard times. Family feuds, overexpansion, and a dilution of its once-exclusive image had left Gucci a shadow of its former self.

Enter Investcorp, the Bahrain-based investment firm. In 1993, they acquired Gucci with the hopes of turning it around, but after several years and millions of dollars invested, the situation looked grim. The brand was still haemorrhaging money and prestige, and there was no clear path forward.

“By the mid 90s, they’ve sunk about $200 million into this thing. It’s totally falling apart. We talked about the brand dilution at Dior with the licenses. Gucci at this point had, I kid you not, 22,000 different licenses [even for] toilet paper.”

That is, until a new dynamic duo took the reins. In 1994, Investcorp tapped Domenico De Sole, a Harvard-educated lawyer with a keen business sense, to become Gucci’s CEO. De Sole, in turn, elevated a young Texan designer named Tom Ford to the role of creative director.

It was a match made in luxury heaven. Ford, who had been toiling away in the Gucci design studio, had a bold and sexy vision for the brand that perfectly captured the hedonistic spirit of the 1990s. De Sole gave him the freedom and resources to bring that vision to life, while also working tirelessly to streamline Gucci’s operations and restore its exclusive aura.

“Ford takes a huge risk. Google Tom Ford Gucci in the 1990s. Porno chic is the term that becomes used. The way you win in fashion is you take crazy risks and shock value. People go nuts for it.”

The results were nothing short of spectacular. Gucci’s revenues doubled in Ford’s first year and kept climbing at a dizzying pace after that too. By 1999, annual sales had surpassed $2 billion, and the once-dying brand was now the hottest label in fashion.

“Overnight, after Tom Ford’s first collections, Gucci revenue doubles. They get back to profitability. At the end of 1994, when Bernard walked away from the deal, by the end of 1995, the brand is so hot that Investcorp IPO is the company on the New York Stock Exchange, and it trades up to a $3 billion market cap. Insane, Bernard just got to be totally, totally pissed at this point.”

Watching from the sidelines, Bernard Arnault could only kick himself. Back in 1994, he had entertained the idea of buying Gucci from Investcorp for around $400 million, only to back out at the last minute after getting cold feet about the brand’s potential.

Now, just five years later, Gucci was worth billions - and Arnault wanted a piece of the action. He quietly began building a stake in the company, hoping to catch De Sole and Ford off guard and engineer a takeover on the cheap.

“In January 1989, LVMH finally does show up. They take a 5% stake in the company that they buy on the market. Burrough interviewing Arnault here writes that, “Arnault was adamant that the plan was not to attempt an immediate takeover of Gucci. He was worried about whether the Gucci turnaround can last. Instead he wanted to build a stake and get on the board for a few years.” Then a quote from Arnault. “Then maybe we make a bit.” This is rational. Gucci was worth nothing a few years ago.”

But “Dom and Tom” were no fools. As soon as they caught wind of Arnault circling, they wasted no time, hatching a series of increasingly desperate schemes to fend him off. They explored possible white knight mergers, flirted with Italian tycoons, and even considered a radical plan to place a huge chunk of Gucci’s shares into an employee stock ownership program - anything to keep Arnault at bay.

“Gucci retains Morgan Stanley to help them here. They advise Domenico that probably what’s going to happen next is Bernard is going to go to Prada and buy the Gucci shares that they own from them. They should go back to Prada and get them to be an ally, but De Sole doesn’t do it. He thinks it would be a sign of weakness to go to Prada because he thinks word’s going back to Bernard anyway, so he doesn’t do it.”

Not going to Prada was foolish, because Arnault did exactly that - and bought Prada’s shares too. Still, to cut a long story short, it was François Pinault, the French billionaire who had made his fortune in timber trading and retail, who came to Gucci’s rescue. Pinault had been quietly watching the drama unfold, and in a series of secret meetings brokered by Morgan Stanley, Pinault hammered out a deal to invest $3 billion into Gucci, giving him a controlling stake and permanent protection from Arnault’s advances.

“They announce the deal and Bernard goes nuts. This could not have backfired more spectacularly. He had the option to buy it on the table for $400 million, to buy Gucci. He missed that. Then he thought he was going to be cute and do this, and instead he just created an incredibly well-capitalized, direct competitor with its own legendary fashion brand within it.”

It was a humiliating defeat for Arnault, and a costly one at that. Not only had he let Gucci slip through his fingers, but in Pinault, he had created a formidable new rival with the capital and the will to challenge LVMH’s dominance of the luxury space.

Over the coming years, Pinault would use Gucci and Yves Saint Laurent as the foundation for a new conglomerate, PPR, which would eventually be renamed to …Kering!

Still… even though Arnault ultimately lost the battle for control of Gucci, he still managed to come out ahead financially.

“LVMH still owns 19% of the company, even though Pinault just came in, bought it, and he's going to transform it into Kering. The three parties, Pinault, LVMH, Gucci, negotiate for two years, until finally, crazily enough, on September 11th, 2001, they announced a deal in the morning Paris time before September 11th happens. LVMH will sell its Gucci stake in two tranches. Because of the appreciation in Gucci stock through all of this, they will end up making a profit of about €760 million.”

Remember, Arnault had started quietly buying up Gucci shares in the mid-1990s, when the company was still in turnaround mode and its stock price was relatively depressed. As Ford and De Sole worked their magic and Gucci's fortunes soared, so too did the value of Arnault’s stake.

“Which led Domenico De Sole to remark, even when he loses, he wins.”

By the time Pinault came to the rescue with his $3 billion investment in 1999, Gucci's shares were trading at many multiples of where Arnault had bought in. And while he may have preferred to use that stake as a catalyst for an eventual takeover, he was able to cash out at a massive profit when it became clear that Pinault had the upper hand.

The Vuitton Machine

LVMH continued to go from strength to strength through the turn of the millennium, with its cornerstone brand Louis Vuitton leading the charge. Originally founded as a maker of custom luggage for the French royal court, Vuitton had by now become a global juggernaut famous for its LV monogrammed leather handbags.

A series of savvy brand extensions and collaborations kept Vuitton feeling fresh and relevant to younger, fashion-forward customers around the world. At the same time, LVMH doubled down on its vertical integration strategy, buying up more of its own suppliers and investing in state-of-the-art factories to exert maximum control over quality and production.

The formula was working. By 2019, LVMH was doing more than $50 billion in annual revenue across its 75 brands. Fashion and leather goods alone accounted for nearly 90% of its profits, with the Louis Vuitton brand making up an estimated 50% of that total. While some critics thought LVMH was over-reliant on Vuitton’s success, Arnault would point to the conglomerate’s unparalleled scale and diversification as a source of unique advantage.

The American Capstone

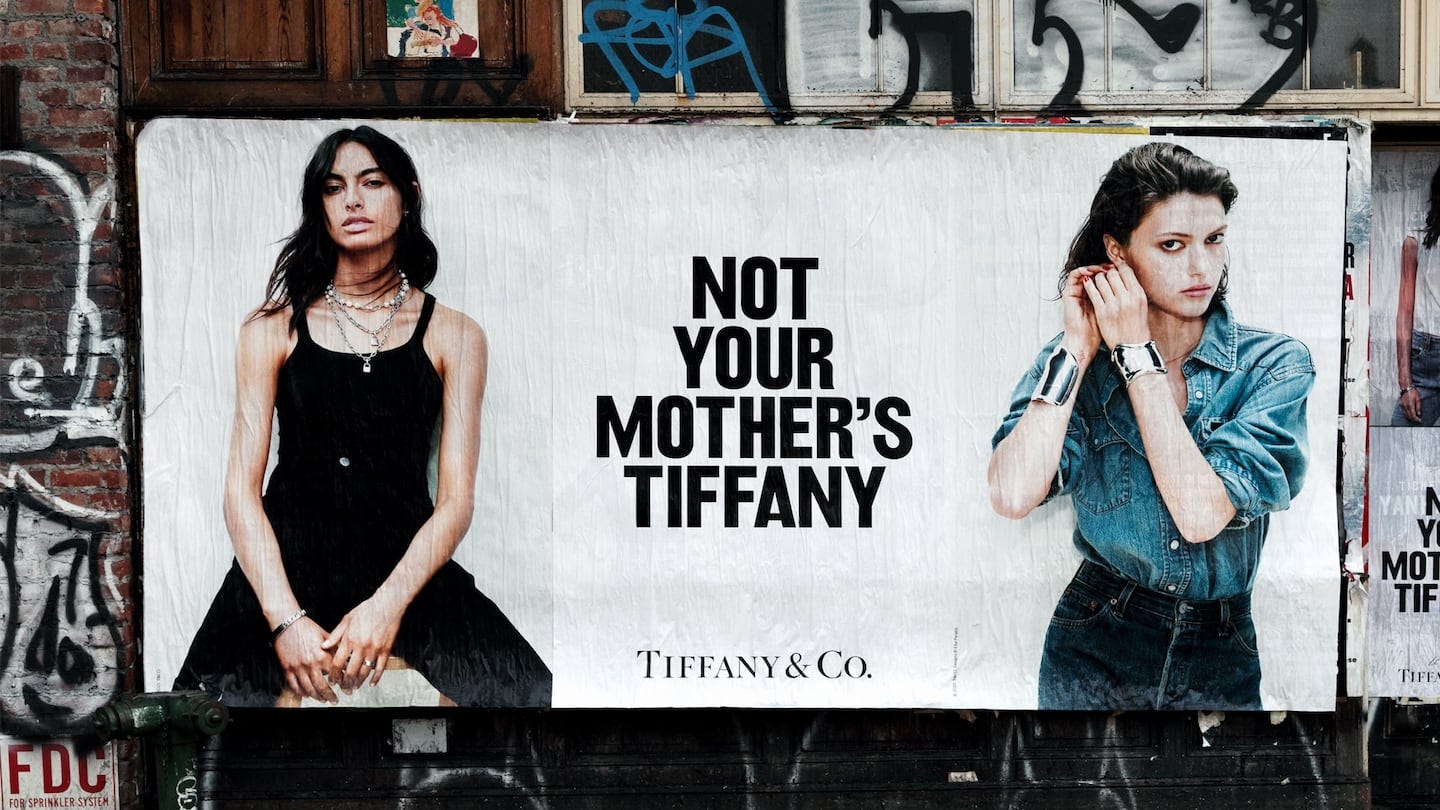

As the 2010s wound down, Arnault had one more major deal in him: Tiffany & Co. The iconic American jeweller, famed for its blue boxes and diamond designs, had been a stock market darling for years but was starting to lose its lustre among younger customers who associated it with their parents’ generation.

“Tiffany is American luxury, and the French conglomerate is coming in to buy it up. The guy who we, America, trained in the art of leveraged buyouts is coming and buying our crown jewel.”

Arnault saw an opportunity to apply the LVMH playbook and restore Tiffany to its former glory. In late 2019, he struck a deal to acquire the company for $16.2 billion, the largest acquisition in the history of the luxury industry.

Of course, he didn’t expect a global pandemic and COVID-19 ravaged the world economy in early 2020, LVMH tried to back out of the Tiffany deal, leading to a fierce legal battle. In the end, Arnault managed to secure a small discount to the original price, but the real drama was yet to come.

“LVMH says, you know what? Instead of $16.2 billion, we’d like to pay $15.8 billion. Tiffany’s pissed. They’re like, why are you doing this? They’re like, oh, Tiffany is mismanaging the company, so it’s losing all this money now that it should have made, so we think it’s worth less, and you signed a term sheet.”

Once the deal closed, Arnault installed his 28-year-old son Alexandre as the new CEO of Tiffany. Together, they set about a sweeping overhaul that included edgy new ad campaigns, buzzy collaborations (like a viral partnership with Nike), and a total revamp of the brand’s musty retail experience. The strategy was summed up by the tagline of one campaign: “Not Your Mother’s Tiffany.”

The early results have were impressive, with Tiffany’s profits roughly doubling since the acquisition. It affirmed the wisdom of LVMH’s playbook: identify a heritage brand with untapped potential, bring it into the fold, and then apply the conglomerate’s vast resources and expertise to unlock new sources of growth. Rinse and repeat.

“This now means that LVMH paid just 13X earnings for Tiffany. It’s pretty impressive.”

The Future of Succession

The looming question around LVMH is what will happen when the 73-year-old Arnault eventually steps down. While he shows no signs of slowing down, he has been deliberately grooming his five children to take on ever-larger roles within the empire he built.

“It’s worth knowing, each of the kids, it’s reported that they each have a 20% stake in the holding company, but there’s a mechanic where they can’t sell their shares for 30 years. There’s an interesting longevity thing built into that, regardless of their operating position within LVMH itself.”

Daughter Delphine, the eldest at 47, is seen by many as the most likely successor, having proven herself as the CEO of Dior. But her younger half-brother Alexandre, 30, is a rising star who has already notched stints at Rimowa and Tiffany. Arnault’s other children are also being cycled through key leadership positions across LVMH’s portfolio brands.

Whoever ends up taking the reins will have big shoes to fill. Arnault’s unique toolkit of creative vision, financial acumen and sheer force of personality will be difficult to replicate. At the same time, he has built LVMH into such a well-oiled machine, with so many capable executives and interlocking synergies, that it is perhaps the ultimate “ride a tiger” business - easy to take over, but dangerous to dismount.

“Unlike other succession battles, which are highly reported—I think the Murdoch family is a great one, people leaking things about each other—this seems ridiculously amicable.”

The Paradoxes of Modern Luxury

Looking back over the arc of Arnault’s career, what stands out is his ability to resolve the paradoxes of modern luxury and weave them into a coherent global strategy. A few key themes emerge:

Heritage vs. Hype: Arnault grasped early on that the value of a luxury brand lies in its history and its timelessness - but also, paradoxically, in its ability to reinvent itself for each new generation. Whether by installing hip young designers, embracing pop culture tie-ins, or launching splashy collaborations, Arnault has kept LVMH’s brands feeling simultaneously classic and of-the-moment.

Scale vs. Scarcity: In the old days, luxury was defined by its exclusivity - the fewer people who could afford a brand, the more desirable it became. Arnault saw that in an age of global wealth creation, that calculus had changed. By scaling up production and distribution, he could make his brands feel more accessible and aspirational to the emerging middle class in China and elsewhere, without losing their cachet.

“Bernard realized that luxury groups could be much better businesses than luxury brands, and have completely different methods of profitability and sustainability, I think that was super astute.”

Control vs. Creativity: A defining tension in any creative business is the push-pull between financial discipline and imaginative freedom. Arnault’s genius was to give his brands and designers the resources they needed to follow their visions, while also applying hard-headed business rigour to the back end of the operation. By owning its own factories, shops and supply chain, LVMH can be maximally efficient in how it turns that creativity into cash.

“The decision of where synergies could be realized in a luxury group and where to stay away from synergies, is probably the biggest value unlock that Bernard has figured out on how this conglomerate needs to work.”

Speaking of which… check out this WSJ article which builds on this theme of control and synergies - LVMH are now becoming a real estate titan. Back to the “store in a store” discussion much earlier, they turned stores into ‘glorified landlords’ - now, they are also the landlords - taking more of the pie, increasing the scale of integration. Incredible.

Dreams vs. Reality: At the end of the day, what Arnault really sells are dreams - the dream of love, glamour, adventure, and self-actualisation. A Louis Vuitton handbag or a Bulgari necklce isn’t just a functional item, it’s a totem of how the owner wants to see themselves and be seen by the world. While Arnault’s own life may be the ultimate manifestation of the luxury dream, he has never lost sight of the fact that dreams require massive underlying infrastructure to sustain them.

Update - 25 June 2024

Bloomberg published a deep dive into LVMH which I thought would be useful to include and reference here.

Brand Portfolio: LVMH now encompasses 75 distinct “maisons” or houses, spanning fashion, jewellery, watches, spirits, and high-end hotels. This diversification has helped LVMH become the 15th largest company in the world by market cap, and the only non-tech, non-oil company in the top 15 besides Berkshire Hathaway.

Hands-On Management: Arnault, at 75, maintains a rigorous schedule of Saturday morning store visits. He meticulously inspects every detail, from product displays to staff attire, sending detailed feedback to executives. This attention to detail extends to all aspects of the business.

Family Succession: Arnault has strategically positioned his five children in key roles within LVMH:

Delphine (49): CEO of Christian Dior Couture

Antoine (47): Head of communications and image at LVMH

Alexandre (32): Executive VP for product and communications at Tiffany & Co.

Frédéric (29): CEO of LVMH's watch brands

Jean (25): Director of watches at Louis Vuitton

This sets the stage for a potential family succession, though Arnault remains tight-lipped about his ultimate plans.

Global Expansion: LVMH has aggressively expanded its presence in emerging markets, particularly China. The company now has 54 Louis Vuitton stores on the Chinese mainland alone, with 23 different LVMH brands opening 58 stores in 2023.

Acquisition Strategy: The 2021 acquisition of Tiffany & Co. for $15.8 billion (slightly less than the initial $16.2 billion offer due to pandemic-related negotiations) demonstrates LVMH’s continued appetite for growth through strategic purchases. Under LVMH’s management, Tiffany's profits have roughly doubled since the acquisition!

Financial Performance: LVMH’s market capitalisation has grown twentyfold in the past 20 years. Their success is particularly notable in the fashion and leather goods segment, which accounts for nearly 90% of its profits, with the Louis Vuitton brand alone contributing an estimated 50% of that total.

Future Outlook: Despite his age, Arnault shows no signs of slowing down. He has raised the CEO retirement age at LVMH from 75 to 80 and continues to eye potential acquisitions, including possible interest in companies like Richemont, Armani, Prada, and high-end watchmakers Patek Philippe and Audemars Piguet.

This update simply reinforces LVMH’s position as a dominant force in the luxury market, with Arnault’s vision and hands-on approach continuing to drive the group’s success.

Epilogue

So there we have it… The story of LVMH. From his audacious early takeovers to his sneaky and tactical battles with rivals, to his bets on unproven designers and untested markets, Arnault has never been afraid to go all-in on his convictions.

Yes, he has enjoyed more than his share of luck and privilege along the way - being born into a wealthy family in a rich country is a good head start. What sets Arnault apart is his uncanny ability to see around corners, to sense where the world is heading before it gets there. He understood the power of a brand before “branding” was a business concept, he saw the rise of China and the global middle class before it became conventional wisdom, and he grasped the importance of vertical integration and corporate culture long before his peers.

In a world that often feels like it’s changing faster than we can keep up, there’s something admirable about the unshakeable constancy of Arnault’s vision. Whether you’re into haute couture or just someone who appreciates a well-made product, it’s hard not to admire the empire he has built and the impact it has had on the global cultural landscape.

The next time you see someone strolling down the street with an LV handbag or unboxing a Tiffany trinket on Instagram, take a moment to consider the commercial creativity and gumption which enabled such incredible success. Luxury may be the stuff of fantasy, but Bernard Arnault has shown, it’s a fantasy built on the very real foundation of ingenious business strategy, perfectly tuned operations, and an unshakeable belief in the power of the dream.

“More than that, he expanded our very conception of luxury and the role it could play in our lives. In an age of affluence and global connectivity, he made the dream accessible to more people than ever before. For that, he will go down as one of the great business titans of our time.”

You can find further reading on LVMH via this link.

Whether you found this interesting, or thought it was pointless - leave a comment! I have a very rough draft on Hermès already, but these take a lot more time than expected… so any feedback would be extremely valuable. There’s also a ton of ‘analysis’ on the back of this which I think would be better suited to a newsletter, so stay tuned for that!

Believe it or not, that “❤️ Like” button is a big deal – it serves as a proxy to new visitors of this publication’s value. If you enjoyed this post, please let others know. Thanks for reading!

This is a fun story too. Bernard Arnault learned about LBOs from John Kluge - they just happened to be neighbours in upstate New Rochelle - and John happened to be the richest man in the USA at the time. So, the richest man in the US, and the richest man today, were neighbours at some point! He even sold this house to John Kluge later on.

At this point, he has formed Groupe Arnault, his family office. Groupe Arnault is essentially Bernard’s personal wealth. They owned some percentage, but not all the Boussac-Dior holdings at this point. The Boussac entity itself had been renamed Agache. Groupe Arnault owns a majority stake in Agache, which owns a majority stake in Dior. Dior and Bon Marche are the only assets left. There are four levels of Russian doll of legal structure here.

Great book by the way!

The official name is Moët Hennessy Louis Vuitton - and the acronym is LVMH. That was a deliberate compromise.

![r/HistoryPorn - 21-years-old Yves Saint Laurent at Christian Dior's Funeral, 1957 [500x662] r/HistoryPorn - 21-years-old Yves Saint Laurent at Christian Dior's Funeral, 1957 [500x662]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!N4l-!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F714b5631-c81c-40db-b11a-70bc59aa645f_500x662.jpeg)

Game of thrones :)

Fantastic job, thanks! 👏🏼

Great idea to translate the pod for the watch lovers here…really enjoyed the read amigo!!!