SDC Weekly 132; Novelty Traps; Coffee Bean Test

Swiss exports contract, LV and De Bethune collaborate, Erich Fromm on tolerating uncertainty, a parenting metaphor about not raising desk divers, and more!

🚨 Welcome back to SDC Weekly! Today I learned from Tony Traina that this month is a perfect month i.e. “a month whose number of days is divisible by the number of days in a week and whose first day corresponds to the first day of the week. This causes the arrangement of the days of the month to resemble a rectangle.” (via the link)

Neat!

Admin note: Speaking of calendars… Our Unofficial Editor is touring a calendar factory and couldn’t check this draft. He’s thinking about firing us because he believes our days are numbered.

We think he’s just taking a month off, so click here to read this post online and ensure you see all corrections made after publishing.

If you’re new to SDC, welcome! If you have time to kill, find older editions of SDC Weekly here, and longer posts in the archive here.

Estimated reading time: ~20 mins

🪤 Novelty Traps

Jack Forster published something yesterday which I had been thinking about for a few weeks now - I had a different draft of this post and I kinda scrapped/repurposed it to accommodate Jack’s excellent thoughts. Jack counted the brands showing up in Geneva this April, and the total is absurd. Watches & Wonders has 66 exhibitors, Time To Watches has 93, Chronopolis (a new independent-focused show) has 20… and that’s not counting the “pirates” (Jean-Frédéric Dufour’s term) who are formally exhibiting at hotels and boutiques around the city. Jack’s pretty reasonable estimate was over 200 brands competing for attention across seven days.

If you wanted to see everyone, you’re looking at ~28.6 brands per day. So at half an hour each, assuming you can teleport between meetings, that’s just over ~14 hours of appointments daily - which of course leaves no time for writing, eating, sleeping, or basic hygiene. Jack, unsurprisingly, did all the math.

What I find fascinating is how everyone involved inherently knows these numbers; the brands know, the journalists know, and I have to presume the organisers definitely know. And yet, the system persists.

Why is that?

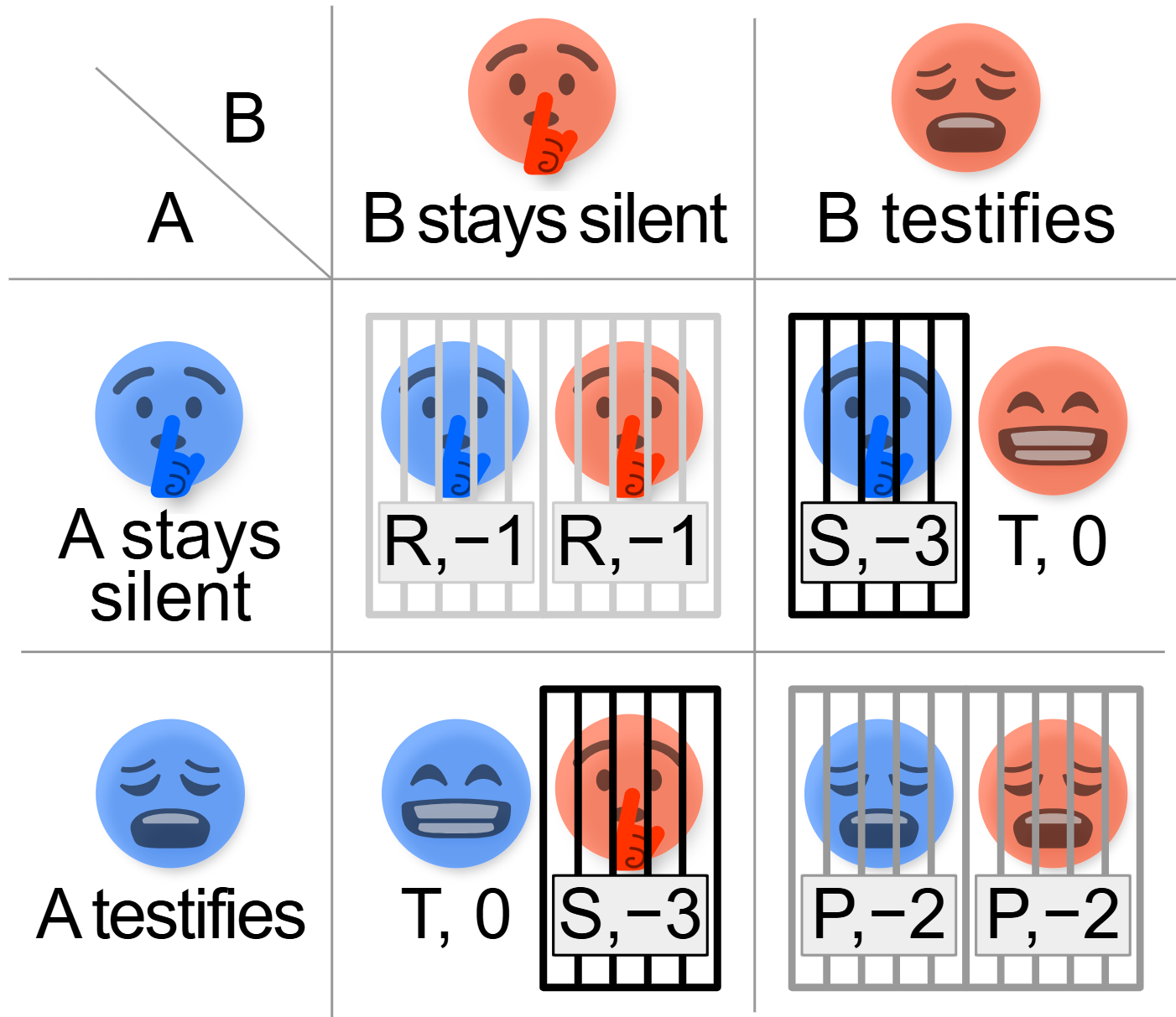

Prisoner’s dilemma (of presence)

It’s kinda obvious that there’s a game theory problem here. If you’re a brand, skipping Geneva feels dangerous. Your competitors will be there, press will be there, collectors will be there... which means your absence might be interpreted as weakness, or worse, irrelevance. So you pay your CHF 5,250 minimum at Time To Watches (or up to CHF 50,000 for a larger stand) and you show up - even if you suspect the return on investment is questionable.

The result is what you see here; everyone’s rational individual decision to attend seems to have created a collectively irrational outcome. Two hundred brands competing for finite attention means most brands get almost none. The noise floor rises, and signal becomes harder to detect, as it were. Except, nobody wants to be the first to defect, because what if their competitors benefit from their absence?

MING decided the game wasn’t worth it this year, and they may be one of the most visible and interesting independents choosing to sit out1. It is reasonable to presume they’ve done the calculation and concluded that their direct relationship with collectors matters more than the marginal exposure from being one of many brands in this sea of brands. They might be right, but then again, MING has the luxury of a fairly established audience. A newer brand doesn’t have that option… or at least, doesn’t think it does.

Attention budget

From a collector’s perspective, you have finite attention, finite time, and but for a select few, finite money. Every brand that demands your attention is competing with every other brand for these scarce resources. This has always been true, but clearly the scale has changed.

Jack notes that in 2015, the SIHH had just 16 brands and Baselworld had 288 watch brands among its 1500 total exhibitors. Combined, that’s 304 brands at two shows, spread across different cities and different times of year. Today we have 200+ brands in one city across one week, and that’s before counting Geneva Watch Days in September, Dubai Watch Week in November, I Am Watch in Singapore, various events in Milan and Prague, and LVMH doing their own thing in January.

The event calendar now creates structural pressure to produce novelty. If you’re attending four or five major shows per year, you need four or five “stories” per year i.e. four or five reasons for journalists to write about you. In other words, the calendar demands content.

As a result, brands create variants instead of innovating; limited editions of existing models, collaborations, new straps perhaps... just to have something to show.

Diversity camouflaging uniformity

Jack makes another great observation; he compares the current watch landscape to the Cambrian Explosion, when life on Earth went from relatively simple organisms to an extraordinary diversity of body plans in a geological eyeblink. But then he notes how mechanical watches haven’t changed in any significant technical aspect since the ~1920s and 1930s.

So yeah, there may be thousands of watch brands out there and tens or hundreds of thousands of models, but fundamentally they’re all variations on the same engineering. The apparent diversity, therefore, is built on necessary uniformity.

This means that when 200 brands show up in Geneva, many of them are, at a technical level, offering essentially the same thing in different packaging. The differentiation is indeed aesthetic, narrative, and otherwise tribal - which we’ve all inherently understood already, but perhaps need a reminder sometimes.

In the end, it’s about which story resonates with you, which community you want to belong to, and which identity you’re constructing. The watch itself (mechanically speaking, anyway) is just table stakes. Todd Searle recently wrote ‘Storytelling Is No Longer Optional’:

There’s a meaningful difference between marketing and storytelling. Marketing exists to sell a product and explain its features. Storytelling helps collectors understand intent, context, and point of view. Storytelling provides context. Collectors tend to recognize when they’re being marketed to, and they also recognize when a story feels incomplete.

Communication-to-production ratio

As you’re aware, Rexhep Rexhepi tends to announce very little, but he also makes vanishingly few watches - and so, this ratio feels appropriate. The scarcity of his communication mostly mirrors the scarcity of his production. When he shows something, it kinda matters a bit more.

Journe makes about 1,000 watches a year, and after the Furtif release, I’m not sure people care as much about what he’ll announce next. There’s a bit of fatigue setting in because communication has outpaced accessibility of the watches (not that this is any fault of the brand’s). Besides, many people just want an Elegante at this point, and even that possibility feels ever more theoretical as time goes by. So for Journe, any announcements are akin to ‘entertainment’ as opposed to information any average person can act upon.

Rolex makes at least hundreds of thousands of watches, and the MS report says, millions of watches. Their relatively restrained communication calendar makes sense because when they announce something, a meaningful number of people might actually buy it eventually… For me, their ratio seems to work just fine.

Now, what about brands making 5,000 to 75,000 watches a year acting like they need the communication cadence of someone making 500,000? I was reading the NYT earlier, and encountered this crazy paid advert from Patek. They’re generating attention they can’t satisfy, creating desire they can’t fulfill, and building awareness among people who will never become customers2. As far as I am concerned, each time they do this, they’re training their audience to tune out altogether.

What gets lost

The system we have now does serve some participants quite well. I mean, the biggest brands get the lion’s share of attention regardless. As Jack notes, some of them don’t even make appointment slots available through the Watches & Wonders booking platform. If you want a meeting, you contact their PR director directly - and even then, unless you’re a VIP you won’t get an appointment3.

The system also serves media outlets with commercial interests; if your business model involves selling watches or partnering with brands, the shows are where those relationships get built and maintained. The editorial coverage is, in some sense, a side effect.

What gets lost is the collector who wants to understand the landscape, or the enthusiast trying to figure out what’s actually good or what they like - this is the person who doesn’t already know which 20 of the 200 brands are worth their time.

Jack puts it well:

Whether or not this constitutes a glut of watch brands depends a great deal on your appetite, but the total number of watches you would have to have some knowledge of, in order to have a broad sense of the state of the industry and of the art of watchmaking, is clearly high enough that no individual watch enthusiast, journalist, or single media entity can keep track of everybody.

This is naturally combined with the presence of interest-specific communities online and in private or semiprivate venues like LinkedIn, which further encourages the Balkanization of the enthusiast and collector communities.