Social Psychology and Watches

The spotlight effect, cognitive dissonance theory, Lake Wobegon Effect, confirmation bias and how this all relates to watch collecting!

I mentioned a week ago that I am taking a course on psychology, and so this covers some of the material from the course itself. I may end up splitting this into a few parts as there is a lot I want to cover! To me, social psychology is the most interesting field of psychology.

Social psychology is the branch of psychology that deals with how we have social interactions and social thoughts, what we think of ourselves, what we think about other people, how we behave in groups, how we think about different groups, and so on. It’s just extremely interesting because these are intrinsically interesting topics - everybody is interested in themselves. It is also interesting because social psychologists have come up with some really cool findings.

For example, people in certain studies were shown photos of Tony Blair and Barack Obama, and then asked, “Who is more American” - now due to unconscious biases and stereotypes, various studies find that Tony Blair is thought of as more American because, due to the colour of his skin, many people think of him as more American.1

Now, these studies, as of late, have generated a lot of scrutiny, and many have argued that the more sexy findings from social psychology, particularly those involving social priming, are not fully robust. In other words, through no fault, no fraud, nothing wrong in the part of the researchers, but just because of various failures to replicate the results meaningfully.

The “Self”

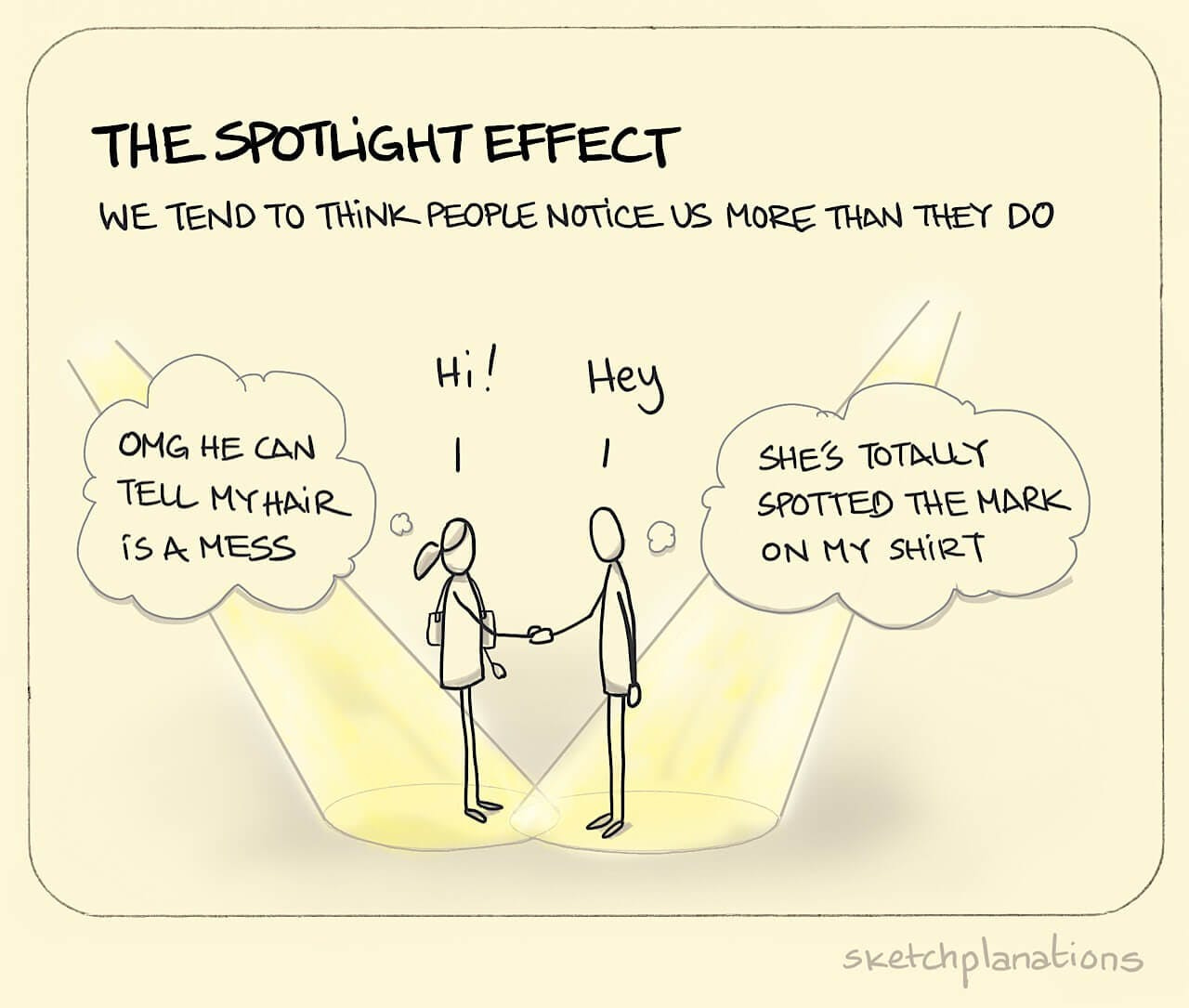

One of the more popular psychology findings of all the time, is known as the spotlight effect. This is where we tend to think everybody notices us, i.e. the spotlight is on us. This was explored by Tom Gilovich and colleagues.2 In this study, they asked undergraduates to wear t-shirts with photographs on them with very disliked people.

At the time the study was done, people didn’t want to have t-shirts with photographs of Hitler or Barry Manilow. The positive t-shirts were very light figures: Martin Luther King Jr. and Jerry Seinfeld. What happened is, they got students to go to class just to interact with people wearing these t-shirts and then later on they asked the students, “How many people noticed your t-shirts?” They also asked the people, “Did you notice what these people were wearing?” It turned out that the people wearing the t-shirts got it wrong, by a large extent. They felt that the spotlight was on them when it actually wasn’t.

Another implication of this in fact was also pointed out by Tom Gilovich. When you ask people what they regret when they die, although this is fairly anecdotal, they regret things they didn’t do. Gilovich suggests that one explanation of why people don’t do things (they don’t take a chance) is that they don’t want to look foolish! The finding that people for the most part aren’t looking, can be fairly liberating.

A second set of biases have to do with positive traits. For example, if you were asked “Compared to everyone else you know personally, how smart are you? From the very top to the very bottom, give yourself a percentage score.”

Of course, if I asked everybody and everybody was accurate, the average would be 50%. You guessed it - that’s not what happens. You probably gave an answer of above 50%, since most people do, and this is sometimes known as Lake Wobegon effect (also known as illusory superiority) which, is based on Garrison Keillor’s fictional town, where all the children are above average.

Ok, so people tend to believe that they are above average... why? One answer is that often when we proceed in life, if we’re fortunate we get a lot of feedback, but the feedback is often positive. Often we hear good things about our performance in certain domains... we are a good cook, considerate husband etc. Another possibility is that when everybody answers the question how smart are you, we apply different criteria for smartness. Maybe one person rates math highly, while others rate chemistry or philosophy highly. Finally, we might have a general healthy motivation to feel good about ourselves, and this shows up in a second, sort of a positive bias, the self-serving bias.

With the self-serving bias, we tend to attribute to ourselves (or to our own traits), positive things, more than negative things. In experiments that look at this, you might ask a student to think about a class s/he did well in, compared to a class s/he did poorly in, or ask a professor about a scientific paper that got accepted or a scientific paper got rejected… and when asked why, there’s a natural human tendency to view our positive accomplishment as a result of ourselves (we worked hard, we’re smart, we put in the effort) but the negative consequences, we view as the cause of other external factors (paper, got rejected because the reviewer and editor are morons, or we did poorly in the class because the professor was unfair or biased themselves!).

This shows up not only in laboratory studies, but in real-world, when athletes describe their successes and failures, when CEOs describe good years and bad years, even when people write accident reports, things that they are plainly responsible for… but still attribute to others.

A final sort of self-serving positive bias is: what we do makes sense... Obviously, otherwise we wouldn’t do it! This falls under a broader theory in psychology known as cognitive dissonance theory, associated with Leon Festinger. The idea is that when when two actions or ideas are not psychologically consistent with each other, people do all in their power to change them until they become consistent… because this inconsistency is unpleasant for us, and it leads to dissonance - humans want to reduce dissonance, and avoid such mental contradiction.

Dissonant self-perception: A lawyer can experience cognitive dissonance if he must defend as innocent a client he thinks is guilty.

From the perspective of The Theory of Cognitive Dissonance: A Current Perspective (1969), the lawyer might experience cognitive dissonance if his false statement about his guilty client contradicts his identity as a lawyer and an honest man.

This manifests itself in different ways; a simple example is that people often attend to information that supports their existing view rather than information that challenges it. You might think this is a strange way for a rational creature to behave. If I really like a certain watch, you’d think I’d be really interested in hearing opinions about why it might not be that good - but the mind doesn’t work that way! Also called the confirmation bias... we often seek out support for our views or ideas. Think about the magazines you read or the websites you go to; for the most part, they often tend to be aligned with your political views instead of challenging them.

Think about when you get a second opinion on something... Everything from what watch to buy, to a second medical opinion on your cancer diagnosis. People often don’t get a second opinion when they get a first opinion they like... but with a first opinion they didn’t like, they immediately ask someone else!

A different manifestation of cognitive dissonance is known as the insufficient justification effect, and this is supported by a famous experiment. Basically, you give people a boring thing to do, and you either pay them very little money, or a lot of money. Then they have to describe the experiment as exciting to somebody else (i.e. they need to lie about enjoying it). Next, you get them to rate what they thought of the task. Interestingly, the people who got paid a small amount of money rated the task as more enjoyable than that people getting a lot of money did. The explanation for this has to do with dissonance. They just did something, lied (did something wrong) - now they need to justify their behaviour! If you get paid a lot of money, you could say, I have enough money to make me do it, so it made sense. Yet, if you did it for only a little money, that may not sit well with you, and so you say, “Well, I must have enjoyed the task, the task was fun, the task was worth doing.” Isn’t that incredible?

Another example is the things that we volunteer for; It turns out, we become more committed to these activities than things that we get paid for. When you get paid for it, you don’t have to love it, but if you volunteer for it, you do have to love it!

Benjamin Franklin has a final example in his advice on how to make an enemy love you; it is both surprising and interesting. He said, go up to the enemy, and ask them for a favour. Why would that make them love you? Cognitive dissonance tells a story; they feel obliged to do the favour, and they didn’t have to explain themselves (why did they do a favour for you) so then they’ll have to conclude (to themselves) they must have liked you!

Concluding thoughts

There are plenty of takeaways, and I have read, and re-read this several times - rather than making this even longer with more of my rambling, I will start with a few short points which draw on the biases mentioned above.

The spotlight effect basically says nobody is looking at you - so don’t worry. The irony of this in the watch community is astounding. Hype is fuelled by this - where some people are paying multiples above retail only to be seen to own something, when in reality nobody even cares!

The Lake Wobegon Effect talks about how everyone overvalues or overemphasises their own position, view, or whatever. So if you buy a watch and then you are asked how good it is, you’re going to say its better than average because this is a reflection on yourself. So just be careful when you seek advice about watches. By now you must have seen the people on Instagram who suspiciously over-promote the things they own, specifically to drive up the prices of their own stuff. Of course there’s an inherent bias here anyway - you could argue they share what they own, because they like it, that’s why they own it. Who am I to argue :)

The self-serving bias talks about the way we concoct stories to suit our own situation... so people who buy something which then shoots up in value, will say its because they're so smart... and people who cash out of a watch too early (prior to the price going nuts) will say they couldn’t help it, or they needed the money and it wasn’t avoidable. Don’t believe everything you hear.

All the rest is food for thought - the next module is going to cover how we make sense of ourselves and others, and explore causes of people’s behaviour - should be fun. Hope this is interesting to you too - let me know what you think!

F

U.S. voters see Barack Obama as 'less American than Tony Blair' according to study | Daily Mail Online (I feel dirty for quoting Daily Mail here, but it isn’t a serious topic so I will allow myself!)

Gilovich, T., & Savitsky, K. (1999). The Spotlight Effect and the Illusion of Transparency: Egocentric Assessments of How We Are Seen by Others. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 8(6), 165–168. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20182597

“The spotlight effect basically says nobody is looking at you - so don’t worry. The irony of this in the watch community is astounding. Hype is fuelled by this - where some people are paying multiples above retail only to be seen to own something, when in reality nobody even cares!”

*Minor correction: No one cares unless you’re in a room with people all reeling from spotlight effect