The Swatch Group's Remarkable Transformation

From Swiss Watch Industry Crisis to Global Leadership Through Innovation and Marketing Savvy

Last year I got hold of this book, but never got around to writing about it. I recently saw some commentary about the Swatch Group, and remembered I had seen some useful context in the book to reference, but had no way of referring to it! Thus, I decided a summary on SDC would be useful to refer back to, and of course, it may genuinely be of interest to many of you as well. If you don’t care about business history, or the Swatch Group, then you can stop reading now.

All the information contained in this summary is taken from the book: A Business History of the Swatch Group: The Rebirth of Swiss Watchmaking and the Globalization of the Luxury Industry by Pierre-Yves Donzé. Bear in mind, I noted some context of my own at the very end such as the MoonSwatch collaborations; But the book came out before those were launched. Therefore, this book review may seem ‘incomplete’ - but I think it lays the groundwork quite nicely for any future posts discussing the Swatch Group.

Don’t forget to comment when you’re done - and hit the ❤ before you leave.

TL;DR

The Swatch Group’s journey from crisis to global leadership is a remarkable story of industrial transformation and marketing savvy. Born from the merger of ASUAG (Allgemeine Schweizerische Uhrenindustrie AG) and SSIH (Société Suisse pour l’industrie horlogère SA) - two ailing Swiss watch conglomerates - in 1983, the Swatch Group emerged as a response to the existential threat posed by Japanese quartz watches. Under the visionary leadership of Nicolas G. Hayek, an outsider to the insular world of Swiss watchmaking, the Group embarked on a bold strategy to revitalise the industry through a combination of rationalisation, globalisation, and emotional marketing.

At the heart of this strategy was a sweeping overhaul of the Group’s production system. Hayek and his team, led by the brilliant engineer Ernst Thomke, set out to streamline the sprawling, inefficient manufacturing base inherited from ASUAG and SSIH. They centralised movement and component production within ETA (Ebauches SA, subsequently renamed ETA SA), slashed the number of calibres, and pushed for greater interchangeability of parts. At the same time, they vertically integrated key suppliers, bringing the production of cases, dials, hands and other essential components in-house.

This rationalisation was accompanied by a major globalisation push, as the Swatch Group established a network of production facilities in ‘low-cost countries’ like Thailand, Malaysia and China. By the late 1990s, the Group had achieved a highly integrated, globally dispersed manufacturing structure that combined Swiss expertise with Asian economies of scale. The result was an unparalleled ability to produce high-quality watches at competitive prices across all market segments.

Still, it wasn’t just about industrial prowess. Hayek understood… in an age of cheap, ubiquitous quartz movements, the only way for the Swiss to differentiate themselves was through emotion, storytelling and brand prestige – something we continue to see today, with independent watchmakers. The Swatch watch, launched in 1983, embodied this new approach. More than just an affordable, accurate watch, Swatch was a fashion statement, a pop culture icon, a blank canvas for creative expression. Its runaway success demonstrated the power of innovative design, clever marketing and global branding to breathe new life into the stagnant watch industry.

Hayek and his team then set about applying the lessons of the Swatch phenomenon to the Group’s higher-end brands. They repositioned Omega, Longines and Rado as affordable luxury marques, focusing on their heritage, craftsmanship and aspirational qualities. They acquired historic names like Breguet and Glashütte Original to gain a foothold in the prestigious world of high complications. And they invested heavily in selective distribution, building a network of proprietary boutiques and forging partnerships with key retailers in high-growth markets like China.

The results of this multi-pronged strategy were nothing short of spectacular. By the turn of the millennium, the Swatch Group had established itself as the undisputed leader of the global watch industry, with a market share of around 20% and an unrivalled presence across all price ranges. Its success spurred a wave of consolidation and vertical integration across the sector, as rivals like Richemont and LVMH sought to emulate its model.

More fundamentally, the rise of the Swatch Group stood for a paradigm shift in how the watch industry operated. The old model of the Swiss watch industry as a loose federation of small, specialised workshops gave way to a new landscape dominated by a handful of vertically integrated, globally active powerhouses. In this brave new world, competitive advantage stemmed not just from technical excellence and craftsmanship, but from the skillful orchestration of design, marketing, distribution and industrial capabilities on a global scale.

As the Swatch Group enters its fifth decade, it seems to be faltering as it faces new challenges, from other groups and smart watches to the rise of a new generation of Asian competitors. Still, with its powerful industrial base, its iconic brands, and its culture of continuous innovation, it remains well positioned to capitalise on these advantages… but it seems to be missing one key thing: a visionary leader. Still, the Swatch Group is still regarded as a symbol of Swiss resilience, adaptability and entrepreneurial flair.

I. The Swiss Watch Industry in Crisis

The Quartz Revolution and Japanese Competition

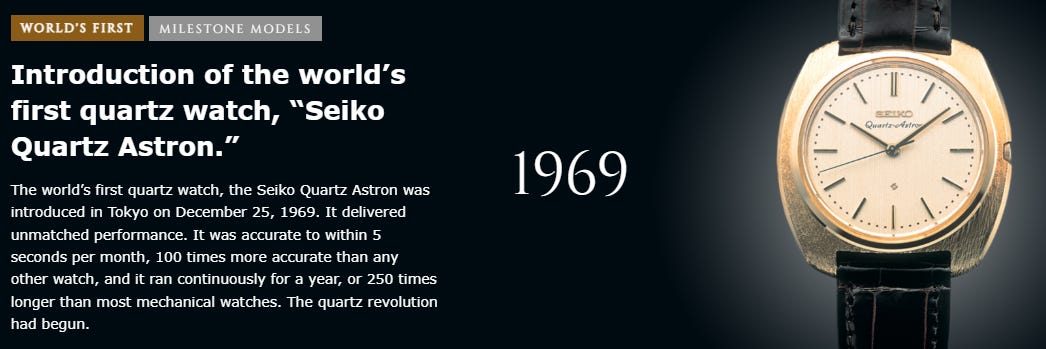

The 1970s and early 1980s represented an existential crisis for the Swiss watch industry. The advent of quartz watches, pioneered by Japanese companies like Seiko, upended the traditional watchmaking landscape. Seiko launched the world’s first quartz watch in 1969, and by the late 1970s, Japanese quartz watches were flooding the global market, thanks in part to a favourable exchange rate between the yen and the dollar.

“Japan continued to benefit from a fixed exchange rate with the United States until 1977, although the yen was revalued from 360 (its fixed parity since 1949) to 308 yen for 1 dollar in 1971. Obviously, this stability is the main reason why Japanese watchmakers did not suffer unduly as a result of the oil price shock: indeed, American imports of Japanese watches grew from USD17.9 million in 1974 to 26.5 million in 1975 and 52.9 million in 1976.”

Even though Swiss companies like Girard-Perregaux, Longines, and Omega soon followed with their own quartz models, they did not match the Japanese in terms of price or production scale. By 1979, quartz watches accounted for nearly 60% of Japan’s total watch production, while the Swiss industry remained heavily reliant on mechanical watches.

The Decline of Swiss Watchmaking

Faced with this onslaught of affordable, accurate quartz watches from Japan, the Swiss watch industry saw its world market share go up in smoke. Swiss watch exports tanked from a peak of 84.4 million pieces in 1974 to just 31.3 million by the early 1980s. Employment in the sector fell even more dramatically, from nearly 90,000 in 1970 to under 47,000 a decade later.

Some of the most storied names in Swiss watchmaking at the time, such as Omega and Tissot, were reporting massive losses by the early 1980s. SSIH was formed in 1930 following a merger between the firms SA Louis Brandt & Frère – Omega Watch Co, in Biel, and Ch. Tissot & Fils SA, in Le Locle, and it became the largest watch manufacturing group in Switzerland when it was founded. SSIH saw its sales fall from CHF733 million in 1974 to under CHF600 million by 1981. ASUAG, the other major Swiss watch group, was basically a holding company which controlled many firms and had a virtual monopoly over the production of watch movement parts. They fared little better, as they were basically state-funded in order to safeguard the watchmaking industry as a whole… but sales were stagnating and profits were drying up. (See image above)

ScrewDownCrown is a reader-supported guide to the world of watch collecting, behavioural psychology, & other first world problems.

Structural Issues

The quartz crisis laid bare the deep structural problems of the Swiss watch industry. Despite some consolidation in the 1960s and 70s, the sector remained highly fragmented, with numerous small, inefficient players hustling for market share. Even the two largest groups, ASUAG and SSIH, were loose conglomerates rather than coherent, integrated companies.

“ASUAG’s turnover posted dramatic growth, reaching CHF1.4 billion in 1974, while it amounted only at CHF 760 in 1970. This expansion was largely due to GWC: watches and finished movements accounted for 43.9 per cent of turnover in 1974 as against a paltry 5 per cent in 1970.”

ASUAG, originally set up in the 1930s to control the production of movement blanks and key components, had diversified haphazardly into finished watches with the acquisition of brands like Certina, Longines and Rado. But there was little coordination between these subsidiaries, resulting in a proliferation of models and duplication of efforts.

“ASUAG diversified into the production and marketing of finished watches with the establishment of the General Watch Company (GWC), a group which initially consisted of seven watch manufacturers (Certina, Edox, Eterna, Mido, Oris, Rado, and Technos), who were soon joined by Longines and Rotary.”

SSIH’s growth was based on a policy of buying up other firms, primarily companies which specialised in the production of particular types of watch which it did not produce itself. This initial phase of concentration was primarily aimed at streamlining the distribution system between complementary brands. It did not involve genuine industrial restructuring, i.e. the “concentration of production facilities.”

SSIH, for the most part, had expanded rapidly by acquiring complementary brands such as Lemania (chronographs) and Blancpain (ladies’ watches). But again, these acquisitions were primarily about boosting scale and market share, not fundamentally rethinking how watches were made or sold. Even worse, in the mid-1960s SSIH made a big bet on cheap, mass-produced mechanical watches (the so-called “pin-lever” or “Roskopf” watches) in a misguided attempt to compete with Japanese quartz pieces on price1.

“As SSIH grew apace, in the mid-1960s it entered the field of so-called “economy” watches, also called roskopf or “pin-lever” watches, which were low-quality, mass-produced mechanical watches. Before the advent of quartz watches, this type of inexpensive watch, primarily produced by the American firm United States Time Co. Ltd. (Timex brand) and several Swiss and Hong Kong companies, became very popular around the world. In 1970, they accounted for 43.9 per cent of the total volume of Swiss watch exports.”

“The drop in Swiss watch exports cannot be directly linked to the quartz revolution – even if it reinforced Japan’s competitive advantage in the early 1980s – and the crisis in Switzerland. Rather, we must look for the origins of the crisis in Switzerland in the problem of process innovation. Mechanical watch production indeed underwent a far-reaching change in the 1950s and the 1960s with the adoption of the mass production system, which was only partially implemented in Switzerland.”

Beneath all these strategic screwups was a complacent, inward-looking culture that had trouble adapting to a fast-changing global marketplace. Many Swiss watchmakers remained wedded to traditional craftsmanship and saw marketing as ‘beneath them.’ They weren’t really prepared to respond to the threat of Japanese mass production or to tap into new consumer trends around fashion and lifestyle.

II. The Founding of the Swatch Group

The Merger of ASUAG and SSIH

By the early 1980s, ASUAG and SSIH were on the brink of collapse. In 1981, a banking syndicate took effective control of SSIH after the group’s equity plunged below 10% of its balance sheet. At ASUAG, losses were mounting despite aggressive cost-cutting measures.

In 1983, at the urging of Switzerland’s major banks, management consultant Nicolas Hayek was brought in to assess the situation. His radical proposal was to merge ASUAG and SSIH into a single entity, the Société suisse de microélectronique et d’horlogerie (SMH), to achieve economies of scale and better coordinate production and marketing efforts. SMH was officially formed in 1983 and would later be renamed the Swatch Group in 1998.

Hayek’s Vision

Hayek, a complete outsider to the clannish world of Swiss watchmaking, brought a fresh perspective to the industry’s woes. He recognised that reviving the Swiss watch industry would require a total overhaul of how it operated, from the shop floor to the retail boutique.

“Usually, key importance in this process is attributed to the Swatch, but this commonly held view must be examined more closely... As we can see, the Swatch had a major impact in terms of marketing strategy. The experiences with the brand during the years 1983–1990 were then adopted by the company’s other brands. However, the Swatch Group’s restored ability to compete was not marketing related. It was based first and foremost on a sweeping transformation of production systems, which boosted product profitability.”

At the production level, Hayek saw the need to rationalise the sprawling, overlapping assortment of movement designs and components used by different brands. He advocated for a more streamlined, modular approach to movement design that would allow for greater interchangeability of parts and improve ease of assembly.

In terms of marketing, Hayek understood how, in an age of cheap, ubiquitous quartz movements, the only way for the Swiss to differentiate themselves was through emotion, storytelling and brand prestige – something we continue to see today, with independent watchmakers. The watch needed to become a fashion accessory, and perhaps even a statement of identity and ‘lifestyle.’

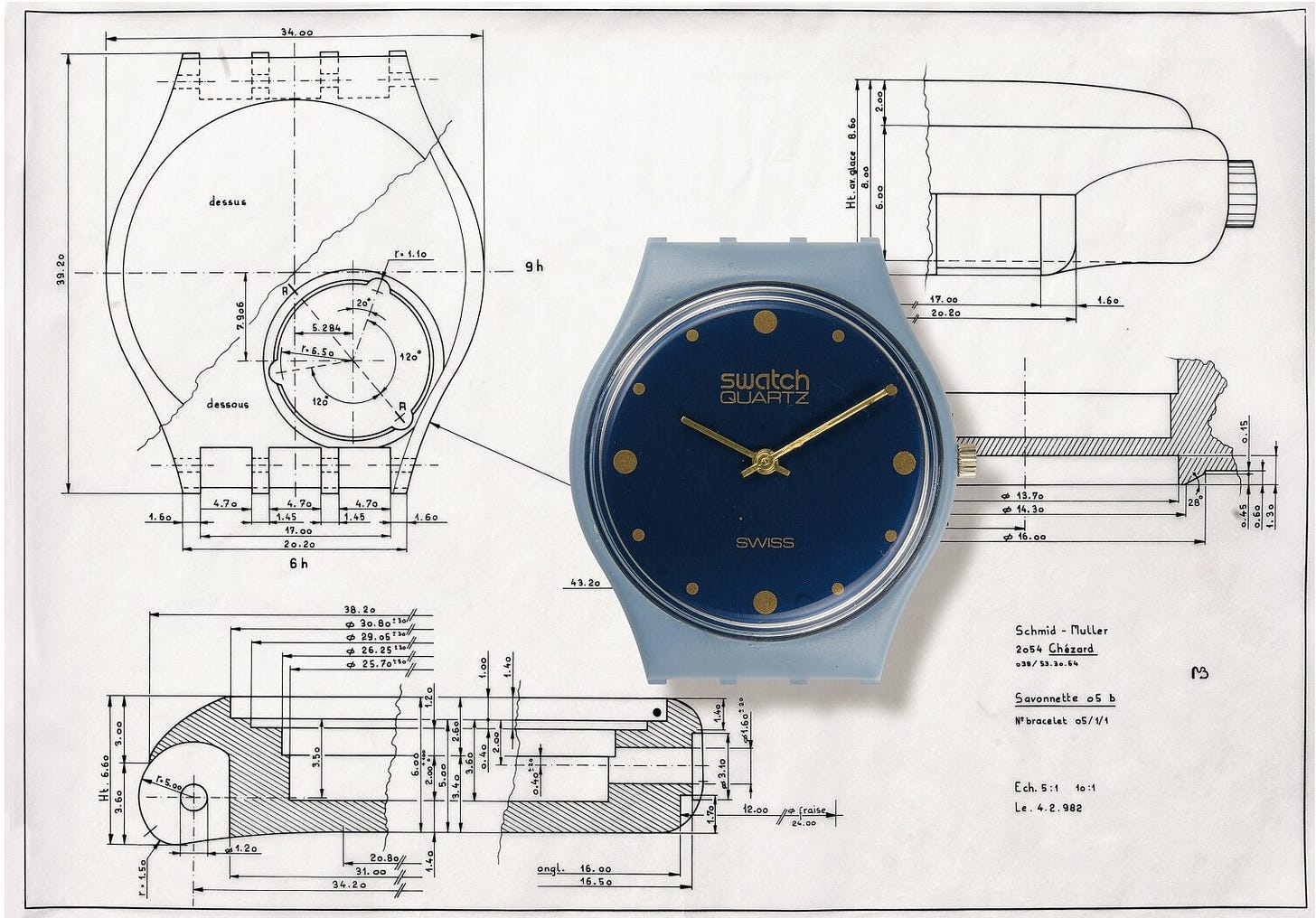

What isn’t covered in the book as such, but covered in excellent detail by this Fratello article, is the journey to actually coming up with, and creating the Swatch watch. It turns out, it was actually Dr. Ernst Thomke, (CEO of ETA at the time) who presented Hayek with a revolutionary vision, leading to the breakthrough of a watch with a single plastic case.

Anyway, if you want to get into the nuances of the Swatch watch itself, the Fratello article is a great resource. So, Hayek pushed for the launch of the Swatch itself in 1983. Although Swatch was a quartz watch, it was positioned as a fun, irreverent fashion item, with an endless array of colourful designs. It wasn’t just about a cheap watch; Swatch showed how innovative design and clever marketing could breathe new life into the quartz watch category as a whole.

At the same time, Hayek was convinced that mechanical watches were the traditional heart of Swiss watchmaking. He believed they could make a comeback if they were pitched as luxury items rather than defunct timekeeping tools. He saw an opportunity to revitalise classic Swiss brands like Omega, Longines and Rado by focusing on their heritage and craftsmanship, as well as tapping into consumers’ emotional side rather than their logical one.

To do this, he figured the Swatch Group would need to exert greater control over all aspects of watchmaking… from component production to final assembly to distribution. By integrating vertically, he could potentially match the Asian competition in quality, price and brand power. Hayek’s ultimate vision was to transform a loose patchwork of brands into a sleek, nimble global powerhouse - all while staying essentially ‘Swiss in character.’

III. Centralised Production

Restructuring in Switzerland

One of Hayek’s first priorities as CEO was to bring order to the productive anarchy of ASUAG and SSIH. Across their dozens of brands and subsidiaries, the two groups were producing hundreds of different movements, many incompatible with each other. Worse, they were relying heavily on outside suppliers for key components, leaving them vulnerable to supply chain disruptions.

To address these issues, Hayek set out to streamline the Swatch Group’s production structure from the ground up. The lynchpin of this effort was the consolidation of all movement and component production within the company ETA SA, formerly ASUAG’s Ebauches SA division.

“One of the first steps taken was to centralise the production of watch movements and parts within ETA SA. This policy was not new as such but marked the continuation and culmination of the strategy for merging subsidiaries of Ebauches SA – the former name of ETA SA – which Thomke had implemented after he was chosen to head the company in 1978. The aim of this policy remained the same over time: the concentration of production was supposed to lead to rationalisation (a reduction in the number of models, interchangeability of parts) and automation of production.”

Under the leadership of Ernst Thomke, ETA undertook a massive streamlining of its movement portfolio in the late 1980s. The number of calibres produced was slashed from over 200 to just a handful of core designs. ETA also worked to standardise parts across calibres, making it easier to produce movements at scale. By 1992, ETA was churning out over 100 million movements per year.

At the same time, the Swatch Group moved to bring more of its component production in-house through a wave of vertical integration.

“…mention should Rationalization of the Production System 41 be made of the purchase of two Swiss firms, Georges Ruedin SA, a watchcase maker (1989) and Méco SA, a crown maker (1990). In France, the Swatch Group acquired two parts makers, Régis Mainier SA (1987) and the Marc Vuilleumier workshop (1990), which were subsequently merged into the Fabrique de fournitures de Bonnétage SA (1991), as well as the company Frésard Composants SA (1991). In Germany, the Swatch Group snapped up a movement and parts manufacturer, Pforzheimer Uhrenwerke PORTA GmbH (1990), which was renamed ETA Uhrenwerke shortly thereafter (1993).”

This vertical integration gave the Swatch Group greater control over its supply chain and allowed it to achieve significant cost savings. It also had a major impact on the Swiss watch industry as a whole, since ETA was the leading supplier of movements to third party brands. By cementing its position as the industry’s “supermarket for movements”, the Swatch Group gained huge leverage over its competitors.

The Globalisation of Production

Consolidation and centralisation efforts within Switzerland were accompanied by a major expansion of the Swatch Group’s production footprint abroad, particularly in Asia. Recognising the importance of being price-competitive in the entry-level and mid-range segments, Hayek and Thomke set out to build a network of offshore assembly sites to complement ETA’s high-end movement production in Switzerland.

The first major move was the establishment of ETA (Thailand) Co. Ltd in 1986 (it was originally in China, in 1985). Initially, the Thai facility was tasked with assembling movements for the Asian market using components shipped from Switzerland. But it soon expanded into the production of cases, dials and hands, becoming a key supply base for the Group’s global operations. By 1998, ETA Thailand employed 3,000 workers, nearly one-fifth of the Swatch Group’s total workforce.

To diversify its Asian production base, the Swatch Group opened a new subsidiary in Malaysia in 1991, Micromechanics Sdn Bhd. It also made a major bet on China, setting up the Zhuhai SMH Watchmaking Ltd facility in 1996.

“The Swatch Group took advantage of its opening of a factory in China to try to launch Lanco, a watch brand for entry-level products. As Nicolas Hayek explained in a 1997 interview with the Geneva daily Journal de Genève, the Lanco product offering was a line of inexpensive watches, sold for a few score francs and produced in the Group’s Chinese factories for world markets, especially the US market, where at the time nearly 80 per cent of all watch imports were in the USD20–25 price bracket.”

The Zhuhai plant, located in Shenzhen’s special economic zone, was originally intended to produce watch movements for export to Hong Kong. But it soon evolved into a key supplier of components for ETA’s Swiss factories.

“The other event which no doubt helped convince the Swatch Group to open a subsidiary in China was the arrival of Citizen Watch Co. in 1994, with an initial production capacity of a million movements.”

By the early 2000s, the Zhuhai facility employed over 1,600 workers, more than 8% of the Swatch Group’s total headcount. At its peak in 2004, it was churning out 80-90 million quartz movements per year, many of them destined for the US market. This allowed the Swatch Group to remain competitive in the sub-$100 price category while focusing its Swiss production on more high-end pieces.

The Globalised Production System

By the late 1990s, through a combination of internal restructuring and overseas expansion, the Swatch Group had transformed itself into a formidable manufacturing machine, with an unmatched ability to produce quality watches at scale. It boasted a highly integrated production structure that married world-class Swiss engineering with low-cost Asian assembly.

“The average number of pieces produced per employee rose steadily, from 3,843 in 1985 to 6,075 in 1992. During this same period, value added by employee went from CHF53,444 in 1985 to CHF89,485 in 1992. As can be seen, Swatch Group’s restructuring enabled its employees to produce more pieces and make more money for the company.”

The results were impressive. Between 1985 and 1992, the number of watches and movements produced by the Swatch Group nearly doubled, from 44.3 million to 86.9 million. Productivity soared, with output per employee rising from under 4,000 pieces in 1985 to over 6,000 by 1992.

This global industrial footprint gave the Swatch Group a significant cost advantage over its rivals, many of whom remained heavily dependent on third-party suppliers. It also allowed for greater flexibility and responsiveness to changes in consumer demand. With its vertically integrated structure, the Group could quickly ramp up or down production of particular components or finished watches as needed.

Still, the Swatch Group’s commitment to offshore production was not entirely smooth sailing; in fact, it didn’t last! In the early 2000s, as Chinese wages began to rise and the threat from low-cost competitors receded, the Group started bringing some production back to Switzerland. In 2005-2006, it closed several Asian facilities, including the Zhuhai factory, and invested heavily in more automated production in Switzerland. This coincided with the Swatch Group’s broader push into luxury-oriented segments where the “Swiss Made” label now commanded a decent premium.

IV. Inventing a New Marketing Strategy

The Swatch Phenomenon

Alongside the transformation of its industrial base, the Swatch Group pioneered a radically new approach to watch marketing in the 1980s and 90s. An obvious example being the launch of the Swatch watch itself in 1983. Sure, Swatch was conceived primarily as a way to make use of excess capacity during the downturn, but it really just morphed into a pop culture phenomenon that ended up redefining the entire quartz watch category.

“This novel marketing strategy was implemented by a new breed of managers, some of whom came from other industrial sectors, especially multinationals dealing in consumer goods, a trend which facilitated the internalization and dissemination of these new practices...What is more, genuine luxury ambassadors work hard to promote the cultural and charity activities of their brand. They display an interest that goes beyond their advertising value as such.”

Swatch’s runaway success marked a fundamental shift in how watches were designed, produced, and marketed. Unlike traditional collections which were planned up to 18 months in advance, Swatch relied on a fast-moving, fashion-driven product cycle. New models were introduced every 1-2 months, often in limited editions tied to specific events, celebrities, or artists. This kept interest high and strengthened Swatch’s positioning as a fun, accessible fashion accessory.

Swatch also broke new ground in how it communicated with consumers. The brand sponsored edgy events like freestyle skiing competitions and urban art exhibitions that positioned it as youthful and irreverent. It opened dedicated stores that served as hubs for the “Swatch lifestyle”. And it tapped into the power of celebrity by recruiting the likes of James Bond, Cindy Crawford, Keith Haring and Kiki Picasso to promote their brands.

“Thus, Hollywood stars are not models who pose wearing their sponsor’s watches; rather, they are extraordinary testimonials for the use of a product, like Marilyn Monroe, who said that a few drops of Chanel No. 5 were all she wore to bed.”

Behind the scenes, Swatch’s success was made possible by a number of key technical and organisational innovations. The main one being a highly automated production process that allowed for the mass customisation of dials, straps and cases. By using interchangeable, injection-moulded plastic components, Swatch was able to churn out an endless variety of designs at an incredibly low cost.

Swatch also pioneered a new global distribution model based on the concept of “glocalisation”. Although design and marketing were centralised in Switzerland, regional offices had significant autonomy to tailor the product mix and messaging to local tastes. Swatch also pioneered a new global distribution model based on the concept of “glocalisation”. Although design and marketing were centralised in Switzerland, regional offices had the autonomy to tailor the product mix and messaging to local tastes. This allowed Swatch to maintain a coherent global identity while still resonating in wildly different cultural contexts around the world.

The Swatch phenomenon showed that Swiss watchmaking could beat back the quartz onslaught through creativity, emotion, and clever positioning. It blazed a trail that other Swiss brands would soon follow as they made the leap into luxury.

The Move to Luxury

In the early 1990s, as Swatch sales began to plateau, Nicolas Hayek turned his attention to repositioning the Swatch Group’s other brands further upmarket. He saw an opportunity to apply the lessons of the Swatch approach - storytelling, lifestyle marketing, scarcity - to the higher-end mechanical watch segment. The goal was to reframe traditional Swiss craftsmanship through the lens of luxury and aspiration.

The first major move in this direction came with the acquisition of Blancpain in 1992. At the time, Blancpain was a dormant brand with little commercial value. But under the leadership of the invisibility wizard Jean-Claude Biver2, it was revived as a prestigious brand, built around traditional watchmaking artisanry. Biver pitched Blancpain as the “guardian of Swiss mechanical watchmaking”, with each piece supposedly made according to centuries-old techniques. It was the antithesis of cheap, disposable fashion - and customers were willing to pay large sums for the privilege of ownership.

Biver On Zenith’s Mission: “Its clear: To produce invisibility and eternity. I don't have yet the right wording for it, but Zenith needs to be invisible and eternal.”

(Chronologically incorrect, with the wrong brand, but I picked the funniest Biver quote!)

Biver’s approach became the template for the repositioning of the Swatch Group’s other heritage brands over the course of the 1990s. Omega, previously a mid-market generalist, was reimagined as a luxury watch… the watch of choice for astronauts and James Bond. Longines leaned into its history as a pioneer of precision timekeeping to become the brand of “elegance and performance”. Even Rado, known for its use of high-tech materials, was given an upmarket gloss.

Central to this luxury masterplan, was a new focus on mechanical movements. Although the Swatch Group continued to produce quartz calibres at massive scale, from a marketing perspective the emphasis shifted dramatically towards the craftsmanship and romance of mechanical watchmaking. ETA began producing a new generation of mechanical movements designed specifically for the luxury segment, such as the Omega co-axial escapement launched in 1999. The Group also invested heavily in movement decoration and finish, to differentiate its calibres visually.

In the race to move upmarket, the Swatch Group did not hesitate to trade on the heritage of its famous names. The 150th anniversary of Omega in 1998 was marked by the publication of a lavish coffee table book and a series of high-profile commemorative events. Lost archives were dusted off to provide inspiration for revivals of vintage designs, and excuses for an unlimited barrage of limited editions.

Acquisitions in the Prestige Segment

To cement its position at the high end of the market, the Swatch Group embarked on a series of strategic acquisitions in the late 1990s and early 2000s. Unlike previous takeovers which were about achieving economies of scale, these were primarily plays for heritage, patrimony and brand power.

The shopping spree began in 1999 with the acquisition of Breguet, a venerable name which had fallen into obscurity. Although a shadow of its former self, Breguet gave the Swatch Group a foothold in the rarefied world of grand complication watches retailing for six figures. While this could be debated, it perhaps also provided valuable savoir-faire in movement design and finishing that could potentially be applied across the Group’s other brands.

The same year, the Swatch Group snapped up Glashütte Original, a German watchmaker with a relatively strong following. Although something of an odd fit for the otherwise Swiss group, Glashütte Original brought both industrial capacity and high-end credibility. It also stood for a bet on the revival of mechanical watchmaking beyond the Swiss stronghold. This buying spree continued in 2000 with Jaquet Droz and Léon Hatot.

V. From Crisis to Global Leadership to Modern Swatch

The Transformation of an Industry Giant

So over the course of 15 years, from 1985 to 2000, the Swatch Group underwent a remarkable metamorphosis. What was once “a disparate conglomerate of weakly integrated Swiss watchmaking firms” emerged as “a centralised, rationalised, and globalised multinational company.”

Unlike its Japanese rivals, who remained fixated on technological innovation as the key to growth, the Swatch Group achieved world dominance through what has been described as “non-technological innovation” - the dovetailing of production rationalisation and sheer marketing savvy.

The Return of Family Capitalism

Over the 1990s and 2000s, the Hayek family steadily consolidated its control over the company:

“This triumphant return of family capitalism in the Swiss watch industry is the outcome of a management policy aimed at ensuring the Group’s financial independence and putting a stop to reliance on banks and the world of finance... Thus, when Nicolas G. Hayek passed away in 2010, there was no break in terms of governance, as Nayla became Chair of the Board of Directors and Nick continued to serve as Chief Executive Officer.”

The financial results of this strategy spoke for itself at the time. Turnover rose 2.5x from CHF2.6 billion in 1995 to CHF6.5 billion in 2010, while net profit margins climbed from 11% to over 16%. Shareholders were rewarded with dividends, while the Group’s capital base was steadily reinforced.

From District to Firm

In many ways, the rise of the Swatch Group marked a paradigm shift in how the Swiss watch industry was organised. The old model of a loose “industrial district” of small specialised firms gave way to a landscape dominated by a handful of vertically-integrated giants.

There were benefits to being embedded in the traditional watchmaking heartland, notably access to mechanical expertise and a deep pool of skilled labour. Even then, the Swatch Group also worked hard to internalise all these capabilities.

“The overall number of Swatch Group production subsidiaries in Switzerland (excluding watch assembly-makers) shot up from 7 in 1985 to 15 in 2010.”

More important was the ability to capitalise on the “aura of Swiss manufacturing excellence” as a tool for marketing.

“The repositioning of watchmaking in the luxury segment and the Swatch Group’s success on world markets are based on a communications policy aimed at tying watches to a territory, as much as they are on the rationalisation and globalisation of production systems.”

Even as the Swatch Group emerged as a true multinational, it continued to trade on the heritage and local roots of its stable of Swiss brands.

VI. The Swatch Group Today

In the years since 2000, the Swatch Group continued to go from strength to strength, and revenues hit CHF8.2 billion in 2019 - iconic brands like Omega, Longines and Tissot became global icons.3

Then, as you already know, the Group began having to navigate tougher times. The smartwatch revolution, led by Apple, disrupted the industry and put pressure on the traditional Swiss model. The Swatch Group responded with its own connected watches like the Tissot Smart-Touch, but it seems unlikely it can compete head-on with tech giants in this category.

There were also been challenges on the regulatory front, with ongoing tussles competition authority admin over the Group’s quasi-monopoly on movement production through ETA. Swatch began gradually winding down movement sales to third parties, putting pressure on rivals to develop their own in-house manufacturing capacities.

Compared to other leading luxury groups, the Swatch Group stands out for its focus on “democratic luxury”. While rivals like Richemont and Hermes play almost exclusively at the high end of the market, Swatch has maintained a presence at all price points - from plastic Swatches to Breguet tourbillons. This has given it unparalleled scale and reach.

Looking Ahead As the Swatch Group enters its fifth decade, it faces an uncertain future. The traditional watch market is under threat like never before, squeezed between smartwatches on one side and a new generation of micro-brands on the other. The COVID-19 pandemic wreaked havoc on the retail sector and upended long-established consumption patterns. They have since had some great success with the Omega Moonswatch collaboration and the Blancpain - Swatch collaboration, but this stuff has been somewhat fleeting in the grand scheme of things.

If the history of this company tells us anything, it is that the Swatch Group has historically shown an uncanny ability to adapt and thrive in changing times. One could argue how much of this is down to Hayek Sr. and his ingenuity, but that’s a story for another day. With its powerful industrial base, its iconic brands, and its continued emphasis on “Swissness” as a core value, the Group seems well-positioned to remain one of the giants of the watch world for at least a few more years. It would be nice if they did justice to the Breguet brand, but I won’t hold my breath.

Whether led by a Hayek or not, one would expect the Swatch Group will be a case study in corporate reinvention for a long time to come.

Believe it or not, that “❤️ Like” button is a big deal – it serves as a proxy to new visitors of this publication’s value. If you enjoyed this post, please let others know. Thanks for reading!

The pin-lever escapement that brought the watch to the masses | THE SEIKO MUSEUM GINZA:

In 1834, the Swiss clockmaker L. Peron invented the pin anchor escapement; then, in 1867, another Swiss clockmaker, G. F. Roskopf, used Peron’s idea of the pin anchor to develop the Roskopf escapement (pin-lever escapement), which could be cheaply manufactured.

Compared with the club tooth lever escapement, the escape wheel had a simpler shape and metal pins were used in place of the rubies that were used in the club tooth escapement to reduce wear on the anchor pallets and impulse pin.

Because this mechanism could be manufactured cheaply, it soon gained widespread use in the pin-lever watch, but owing to its low precision, rapid rate of wear and short lifespan, it was treated as a disposable watch. This type of watch disappeared almost entirely when cheaper quartz watches later became popular.

Over the years I have read numerous articles, commentary and history of, as well as the evolution of, the Swatch Group but none of it has even approached the magnitude of this avalanche of well organized data, stories and trivia. (Of course there’s likely a whole book that goes even more into detail than this article but I doubt I would feel the interest to go much deeper)

Well written and as concise as something as big as this could probably be!

👏🏻👏🏻. 🫶🏼🥂

BTW….. I wouldn’t mind an offshoot of this re: the rise and accomplishments of JCB from this era on……Blancpain, Omega, Hublot et al with a big dash of the inside dirt and grit😜

It is interesting that they somehow didn't ever reach the heights of the 2010's during the post-pandemic surge. I always assumed that boom was the most successful business period for the industry. Measured by revenue, it is a good bit off.