The Spectrum of Independence in Watchmaking

How Constraints and Creativity Define Independence in Horology

Earlier this week I asked Ken from Delugs: “What defines an independent brand?” After a brief response on Instagram, I felt compelled to dig a little deeper. The word independent seems to be used rather loosely and its true meaning is difficult to pin down. It seems to change with context and perspective. Let’s explore this and see where we end up.

Estimated reading time: ~17 minutes

Historical Context

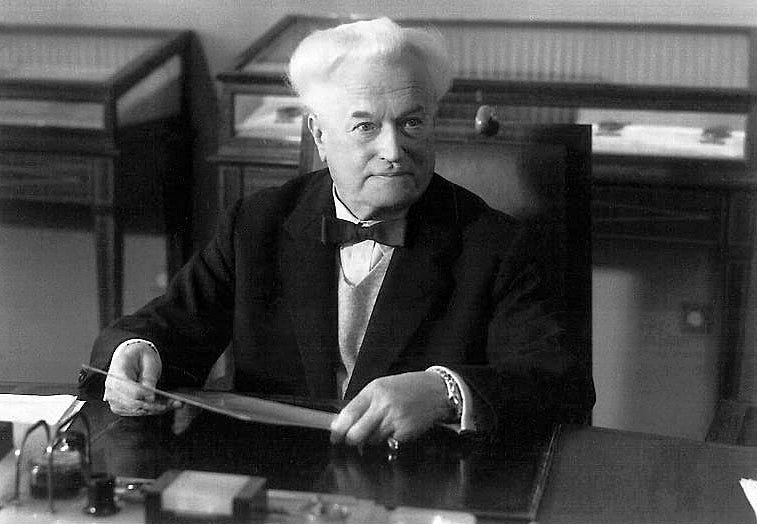

In the early days, most watchmakers were independent artisans, crafting watches from start to finish in small workshops. This changed with the industrial revolution, which saw the rise of larger manufacturers and the beginnings of mass production.

The 20th century brought further shifts. The formation of large watch groups began to consolidate the industry, with brands like Longines and Omega joining forces as early as 1930 to form SSIH (later part of what would become the Swatch Group). Random extra if you missed it:

The quartz crisis of the 1970s and 80s was a pivotal moment. It decimated much of the traditional Swiss watch industry, leading to further consolidation as brands struggled to survive. Paradoxically, this crisis also sowed the seeds for a new wave of independence. As established brands faltered, it created space for innovative watchmakers to emerge.

The late 20th and early 21st centuries saw a resurgence of interest in mechanical watches, sparking a renaissance in independent watchmaking. Pioneers like François-Paul Journe, Daniel Roth, Philippe Dufour, and Roger W. Smith began to gain recognition, championing a return to traditional craftsmanship and innovation outside the constraints of large groups.

Today, we see a diverse landscape where large conglomerates coexist within a thriving scene of independent watchmakers, each navigating their own path to creative expression.

ScrewDownCrown is a reader-supported guide to the world of watch collecting, behavioural psychology, & other first world problems.

Ownership Structure and Independence

Watchmaking independence can be shaped by ownership structures, and they all offer their own advantages and constraints - as you’ll see, there’s a fair bit of overlap.

Privately Held and Family-Owned Companies form a substantial portion of independent brands. Notable examples include Patek Philippe, Rolex, and F.P. Journe, with François-Paul Journe holding the majority stake and minority investors like Chanel. These structures typically allow for long-term planning unfettered by the pressures of quarterly results. Decision-making in such companies is often driven more by passion and legacy than purely financial motives, and this fosters greater creative freedom and encourages investment in innovation. These brands also tend to preserve their company culture and values across generations, although it remains to be seen how the likes of Journe, Gauthier and MB&F tackle succession. That said, the degree of independence will vary within this category, largely depending on the extent of family involvement in day-to-day operations and the presence of non-family executives in key positions.

Conglomerate-Owned Brands present a different model of operation. Brands under large groups like LVMH, Richemont, or Swatch Group often benefit from access to greater resources but may face more corporate oversight. The degree of autonomy, however, will vary significantly. Some brands, like A. Lange & Söhne within Richemont, seem to maintain a high degree of operational independence, while others like Omega within Swatch Group may be more tightly integrated into the parent company's structure and strategy. This balance between resource availability and creative autonomy often defines the nature of independence for these brands.

A third category emerges in brands that are Independent, With or Without External Investors. F.P. Journe and Romain Gauthier exemplify this model with investors, with Chanel holding a minority stake. This structure can provide access to additional capital and resources, as well as potential strategic partnerships. Crucially, it often allows for the retention of creative and operational control by the founding watchmaker or family. This model seems to balance the benefits of external investment with the preservation of the brand’s core identity and vision. The likes of Kari Voutilainen, Vianney Halter, and similar watchmakers are simple examples of this model without investors.

A Foundation-Owned Brand, i.e. Rolex under the Hans Wilsdorf Foundation, is essentially unique. In this model, profits are typically reinvested in the company or used for philanthropic purposes. This structure is geared to ensure long-term stability and independence, align the company’s goals with broader social objectives, and protect the brand from acquisition. It represents a commitment to perpetuating the founder’s vision into perpetuity. There is nothing quite like this, and I think we will not see another in the watch world.

Regardless of the specific ownership structure, several factors determine the impact on a brand’s independence. These include the decision-making processes (who has the final say on strategic decisions), financial autonomy (how profits are allocated and reinvested), brand identity preservation (how the unique character of the brand is maintained), and long-term outlook (whether the focus is on short-term gains or long-term brand building).

In practice, as you’ve probably noticed yourself, the degree of independence often depends more on the specific governance structures and company culture than on the broad category of ownership. Family-owned businesses like Patek Philippe and privately held companies like Rolex can operate with similar levels of independence, prioritising long-term value and brand integrity over short-term profits. The true measure of independence lies in how these structures enable or constrain a brand’s ability to pursue its vision in horology.

Technical Independence & In-House Production

At its most fundamental level, independence in watchmaking can be associated with the ability to produce components and movements in-house. If Max has a wacky idea, and can’t make any of the parts, what is he? To a casual observer, he’s just a fellow with a wacky idea, not a watchmaker! Does that mean vertical integration is the gold standard of independence because it allows brands to control every aspect of producing their watches? Well, as you already know: “It depends!”

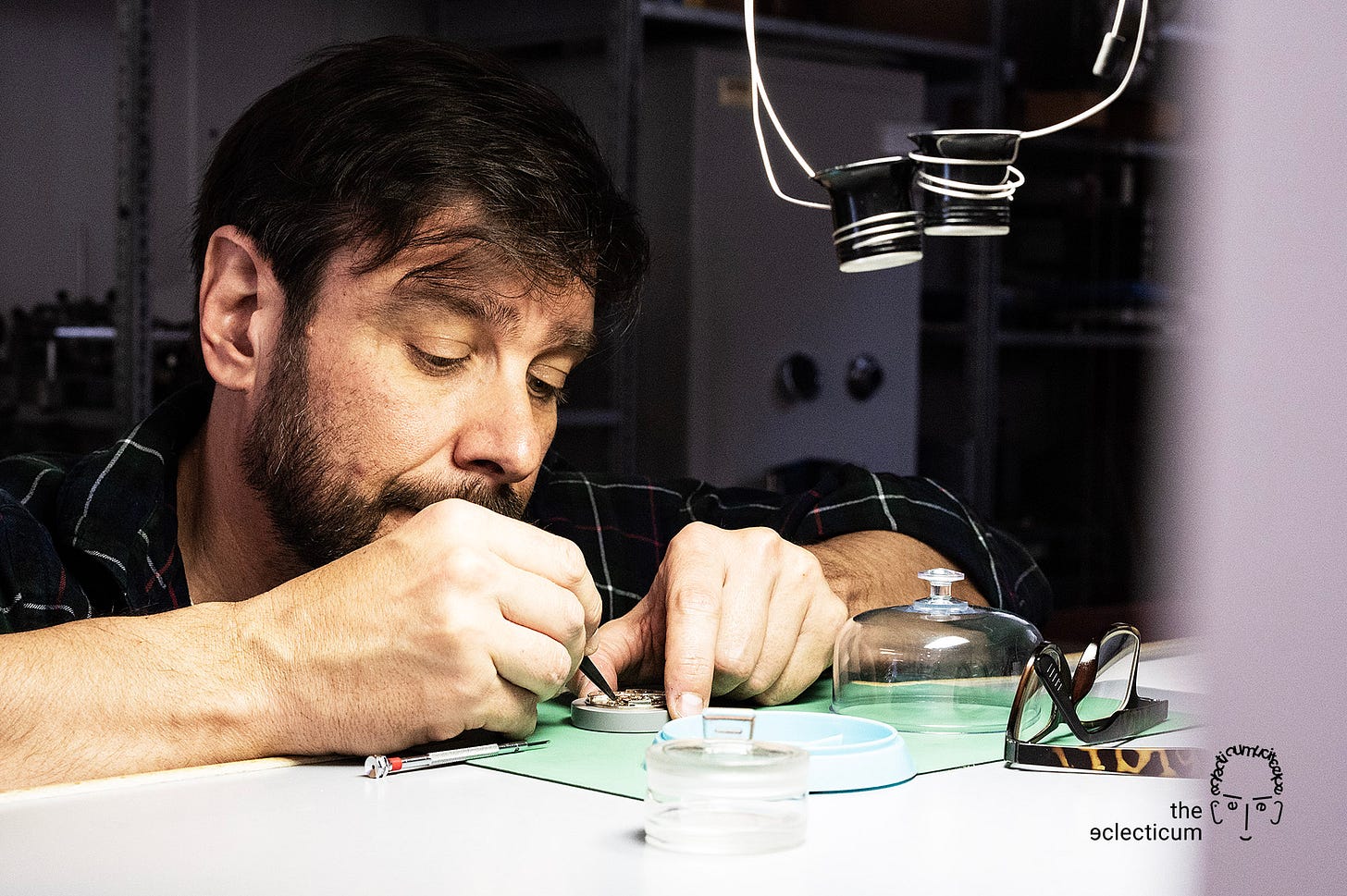

Romain Gauthier and François-Paul Journe demonstrate this approach. They seemed to understand the value of controlling all aspects of production and took steps over the years to bring most of their production in-house. They pride themselves on manufacturing nearly every component. This level of control allows them to realise their visions, without the burden created by the limitations of off-the-shelf parts or manufacturers’ capabilities. They also now supply parts to other prestigious names in the industry. They are, true to the definition of the word, independent.

Freedom from External Pressures

Well, I see you rolling your eyes at those examples. “But they are partially owned by Chanel” I hear you whine. Relax. You are right, the ability to operate without external financial pressures or the demands of shareholders can grant a brand more freedom to pursue its vision without compromise. In theory, anyway. I know firsthand, both Journe and Romain Gauthier are left to their own devices, and the Chanel involvement has had no impact on their creative freedom. Will it be the same for MB&F? Well, as I mentioned the other day, who knows? All I am saying here, is: “It depends!”

Rolex is perhaps the ultimate example of financial independence in the watch world. As a privately held company with seemingly infinite resources, Rolex has the luxury of operating on its own terms, free from the pressures of quarterly reports or shareholder demands.

That said, this financial independence doesn’t necessarily translate to complete creative freedom. Rolex’s very success and market position inherently creates constraints. This leads to a more conservative, iterative approach to design and innovation. Rolex is unmistakably Rolex. They could in theory do a wild design, but it wouldn’t necessarily ‘fit’ with the brand they have built. So, for all the financial freedom they enjoy, the creative freedom may be ‘muted’ by their scale and brand value.

On the other hand, smaller independent brands like MB&F or Urwerk demonstrate how limited financial resources can sometimes lead to greater creative freedom. Unburdened by the need to maintain a vast infrastructure or meet mass-market demand, these brands can afford to take greater risks in their designs and concepts. The flip side of this, is they are forced to balance their insanity with the real possibility that the R&D spend on a watch which fails, could lead to financial ruin!

Creative Independence

Perhaps the most crucial aspect of independence in watchmaking, at least as far as enthusiasts are concerned, is the freedom of thought and design in mechanical watchmaking. This is the ability to push boundaries, challenge conventions, and create truly innovative watches, both technically and aesthetically.

Here, size and resources can be as much a hindrance as a help. While a brand like Rolex has the technical and financial means to create virtually anything they can imagine, they are constrained by their own history and market expectations. The weight of their iconic designs and the expectations of their clientele probably act as invisible chains, limiting their ability to truly innovate in design. This is where Tudor shines, as a result.

Contrast this with a brand like MB&F. Despite limited resources, MB&F displays far greater independence of thought in their designs. Büsser’s philosophy is encapsulated in his own words:

“I created MB&F to do what I believe in: creating three-dimensional kinetic art pieces that give time. I’m not here to give you the time – your mobile phone does that far better than any mechanical watch.”

This freedom to explore radical new ways of displaying time stems directly from the lack of historical baggage and market expectations. This also goes both ways. MB&F can’t reasonably create a ‘normal looking’ time-only watch and charge 6-figures for it; it won’t ‘fit’ their brand. This implies they too, are constrained – just in a different way! Of course, this constraint on creativity (in the negative) is precisely what enthusiasts look for when defining an independent brand, so this tracks.

The Microbrand Phenomenon

In recent years, the rise of microbrands added another dimension to the concept of independence in watchmaking. These small, often crowdfunded operations represent a different facet of autonomy.

While microbrands lack the resources for in-house movement production, they often display the highest degree of creative independence (albeit often just copying established designs, but let’s not go there!). Freed from the constraints of tradition or market expectations, microbrand creators can explore niche designs and concepts that larger brands might shy away from.

Truth be told, to me these are more about making money, and less about creativity and innovation. Not always, but more often than not. When it ain’t solely about money, however, the results can be astonishingly good, too!

Take, for instance, Halios Watches. Despite using sourced movements, Halios has built a devoted following through its distinctive designs and limited production runs. This demonstrates that independence in watchmaking isn’t solely about technical capabilities, but also about the freedom to pursue a unique vision.

My favourite example in this space is Kollokium. This is a complete departure from the norms of what has come before it. Their watches represent precisely what any established brand would shy away from.

The Collaborative Model

Interestingly, some brands have found a path to ‘independence’ through collaboration. MB&F, for instance, celebrates its reliance on external specialists. As you all know, the F in MB&F stands for ‘Friends’, acknowledging the network of suppliers and artisans that contribute to these creations. More recently, we’ve seen Simon Brette use this model to great effect too.

Some might say this approach challenges traditional notions of independence, and others will argue true autonomy lies in the freedom to choose how one operates. Focusing on design and conceptualisation while outsourcing technical production may seem like an easy way to do things, but brands like MB&F and Simon Brette will say their watches might not be possible if they were constrained by their own manufacturing capabilities. Honestly, I’d tend to agree, and my reasoning is based on the historical context of Établissage - which forms the foundation of the Swiss watch industry today. Here’s a whole post about it if you don’t know what this means.

An alternate perspective - AHCI

The Académie Horlogère des Créateurs Indépendants (AHCI) offers another perspective on independence in watchmaking; one which perhaps serves as a valuable counterpoint to the various forms of independence we’ve explored thus far. Founded in 1985 by Svend Andersen and Vincent Calabrese, the AHCI was established to support and promote independent watchmakers who might otherwise be overshadowed by large brands and corporations.

While the AHCI doesn’t explicitly define “independent watchmaking,” their membership criteria and mission provide insight into their view of independence:

Creative Autonomy: AHCI members must independently develop and produce their creations. This suggests a view of independence which prioritises personal creative vision over market demands.

Technical Mastery: Candidates must obviously demonstrate skills in watchmaking, implying that independence includes a high level of technical proficiency and hands-on involvement in the creation process. This one would exclude so many brands and most microbrands - Max Büsser can’t make watches, most microbrands are founded by people who can’t make watches, and the likes of Simon Brette - who can design calibres and is a watchmaking engineer, also can’t make his own watches. Very interesting!

Smaller-Scale: AHCI members typically work as individuals or in very small teams, producing limited quantities of watches. This contrasts with the mass production model of larger brands and even some other independent watchmakers such as H. Moser & Cie or even F.P. Journe, depending on how you define ‘small’ scale.

Innovation and Tradition: The AHCI aims to foster innovation while preserving horological traditions, suggesting that independence in watchmaking involves both respecting the craft’s heritage and pushing its boundaries. Arguably, Rolex does qualify strongly in this regard - every week I find a couple of new watch-related patents from Rolex; excluding the design patents, they still do a lot for watchmaking innovation too.

Peer Recognition: The requirement for support from existing members and unanimous approval by the general assembly indicates that independence, in AHCI’s view, includes recognition and validation from fellow master craftsmen.

So, unlike privately held or family-owned companies, where independence tends to be defined by corporate structure and ownership, AHCI’s view focuses more on individual craftsmanship. Their concept of independence is rooted in the personal skills and vision of the watchmaker, rather than the financial autonomy of a large company.

This perspective also stands in contrast to brands with external investors or those that are part of larger conglomerates. While these companies might maintain a degree of creative independence, AHCI members, at least publicly, seem to retain complete control over both their creations and business decisions. This level of autonomy allows for a direct expression of the watchmaker’s artistic and technical vision, unfiltered by corporate considerations. Did Claude Sfeir influence Dufour’s watchmaking decisions? Does Chanel actually influence Journe’s decisions? We will never know the absolute truth here, but giving them the benefit of the doubt, this all tracks. Fine.

The AHCI model definitely diverges from collaborative approaches to independence. Brands, like MB&F, Simon Brette, and Fleming, have embraced collaboration as a form of creative freedom. AHCI’s philosophy, however, emphasises self-reliance in the creation process. This doesn’t mean AHCI members work in isolation, but rather that they maintain a high degree of personal involvement and control throughout the watchmaking process. It’s a tough one - a blurry line for sure.

AHCI’s approach basically cancels the idea of microbrands being considered independents. Microbrands tend to rely heavily on outsourcing to realise their designs, and AHCI members are expected to have a high degree of in-house production capability. This emphasis on technical self-sufficiency is seen as crucial to maintaining true creative independence, and frankly, I can’t disagree at all.

In many ways, I think the AHCI model represents perhaps the ‘purest form’ of watchmaking independence, as it places the individual watchmaker’s vision and skills at the forefront. That said, this is still just one point on the broader spectrum of independence in watchmaking we’ve explored here.

As we’ve seen, independence in the watch industry can manifest in many forms, from financial autonomy to creative freedom, from technical self-reliance to innovative business models. Obviously the AHCI’s perspective is highly respected and influential, but it is not the only valid interpretation of independence in the watch industry.

What the AHCI model does highlight - yet again - is the importance of individual creativity, technical mastery, and a deep respect for horological traditions in defining independence. These values can be expressed to varying degrees across the spectrum of independent watchmaking, from one-person workshops to larger independent brands.

In the broader context then, the AHCI view underlines the fact that at its core, watchmaking is an art and a craft first, and a business second. This is an important counterpoint to all the commercially-oriented definitions of independence.

P.S. Thanks to Gary G for the feedback which led to this AHCI section. I think it added a lot of value to the conversation.

Conclusion

In the end, independence in watchmaking is less a fixed state and more a spectrum of possibilities; each one representing a different configuration of creativity, technical prowess, and entrepreneurial spirit.

From the lone artisan hunched over their workbench in the Vallée de Joux to the bustling ateliers of Geneva, from the corporate boardrooms of Richemont clowns to the Kickstarter websites of the latest microbrand, independence in watchmaking wears many faces. It is Philippe Dufour, watching his daughter hand-finishing a bridge with a stick. It is Mr. Journe, inventing a new escapement to firmly exit the shadow of his mentor George Daniels which only exists in his own head. It is Max Büsser, conjuring up horological machines while sitting on the toilet. It is Jean-Claude Biver, turning shite brands into juggernauts. And yes, it is even the opportunistic microbrand founder, designing watches in his garage as a side-hustle.

Independence, perhaps like time itself, is relative. Rolex, with its foundation ownership and near-mythical status, is independent in ways that would make most Fortune 500 CEOs weep with envy. Yet, it feels shackled by the very expectations it has created. Meanwhile, MB&F, operating on a financial tightrope, has the freedom to create watches that look like they’ve time travelled from a future where Daft Punk rule the world. Who’s more independent? The answer, as I’ve told you already, is “it depends.”

The AHCI crowd might argue true independence lies in the ability to conceive, design, and execute a timepiece from start to finish. It is a compelling argument that goes back to the roots of watchmaking as a craft. The thing is, in an age where collaboration can lead to creations as mind-bending as Urwerk’s or as widely celebrated as Brette’s, is this definition too narrow?

Perhaps independence in watchmaking is less about who owns what or who makes what, and more about the freedom to pursue a vision without compromise. It may just be about having the balls to say, “This is what I believe in, this is what I’m going to make, and if you don’t like it, well, go fvck yourself there’s always G-Shock.”

If this were a chess game, the kings and queens might be the Rolexes and Pateks of the world, but it’s going to be the knights – the Journes, the Urwerks, the Sopranas – that keep things interesting. They’re the ones making the unexpected moves, jumping over established norms, and occasionally knocking over a pawn or two.

Oh yes, let’s not forget the pawns - those scrappy microbrands, one Kickstarter away from glory or obscurity. They might not have the resources or the pedigree, but they’ve sure as hell got moxie in spades! In a world where the big brands play it safe, these underdogs are taking risks, filling niches, and sometimes, just sometimes, changing the game1.

So, what’s the endgame for independence in watchmaking? There isn’t one. This is an ongoing match, with new players entering, old guards adapting, and the rules constantly evolving. The only constant is change, and the willingness to embrace it.

And that, I guess, is what makes this industry tick. This is exactly why we obsess over these tiny objects, why we debate the merits of in-house movements versus ébauches, why we lose sleep over whether to pull the trigger on that limited piece which costs more than a house… Because in each watch, we are so delusional, we see a reflection of its creators’ independence, their vision, their audacity to imprint their ideas on the canvas of time.

So the next time you strap on your watch, take a moment to appreciate not just the craftsmanship, but the independence that made it possible. You’re basically wearing a declaration of independence.

Believe it or not, that “❤️ Like” button is a big deal – it serves as a proxy to new visitors of this publication’s value. If you enjoyed this post, please let others know. Thanks for reading!

I was thinking of Studio Underd0g collaborating with Moser when I said this.

“It depends” is probably the most appropriate qualifier to add to the calculation of horological independence. Among the verticals of independence you shared, creative independence is what rings most true to me.

Whether it’s Max sitting on his toilet concocting his latest invention, or other brands essentially saying GFY and buy a G-Shock, that willingness to tread an unexpected path is what I would have to see from a watchmaker who is said to be independent.

Independence can take many forms as you say and might be found in odd places. One example which might cause others to question my sanity or horological bona fides is my appreciation for the independence of Glashutte Original. Looking at their catalog over the past decade or two one finds several completely unexpected pieces from GO, pieces which I maintain show an independent streak completely detached from their corporate ownership.

Many thanks for yet another thought provoking and well written piece, my liege.

I enjoyed your thinking here. As somebody who somewhat recently excised their last watch made by a conglomerate, It's something I've given some thought to myself. While it's nifty (and self-satisfying) that I've curated a smallish collection of Independents, from microbrands to entry-level Haute Horology, I'm not necessarily opposed to owning another watch from Swatch, LVMH or Richemont, but I don't exactly find myself inspired by their output either and in some cases their business strategies (looking at Richemont in particular...) are active turnoffs.