SDC Weekly 117; The Rolex Legacy Book Review; Rory Sutherland's insights applied to watch collecting

Johnny Davis’s Olmsted interview, on cutting stones and building cathedrals, new memory and consciousness research suggests memories aren't stored in your brain, and lots more.

🚨 Welcome back to SDC Weekly! This is twice as long as usual… apologies in advance. The book review is not paywalled, and free for all.

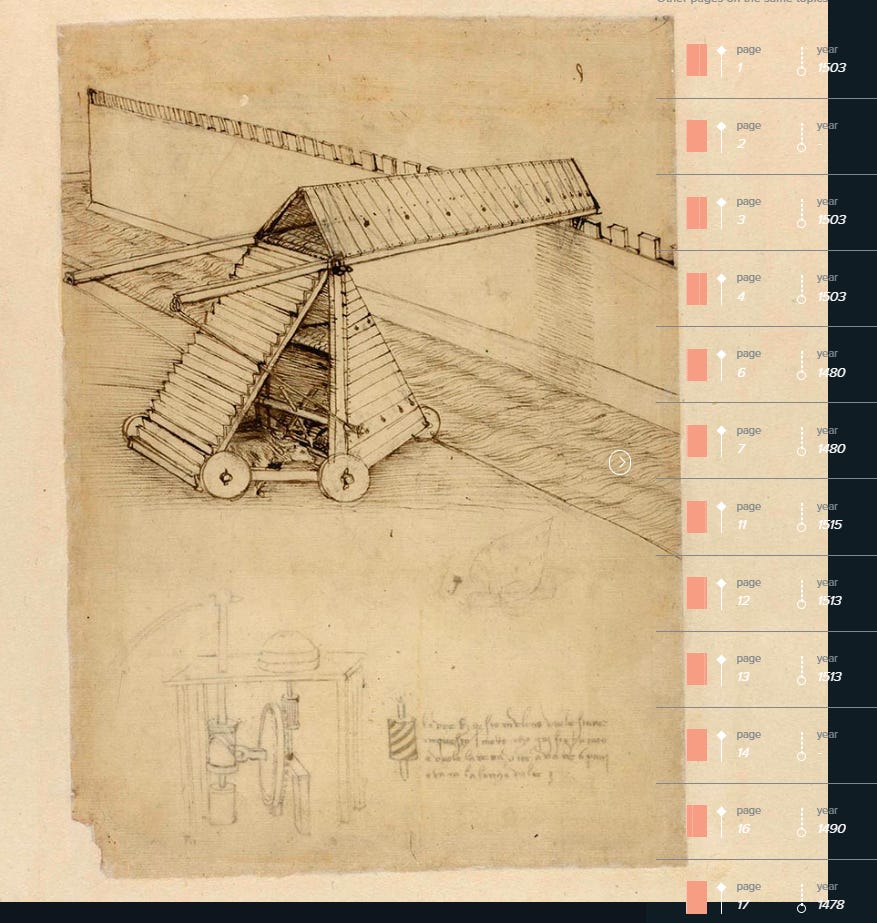

There are also several awesome nuggets this week; one of them being an exploration of brain and quantum science in the bonus link at the end, and another is a fully digitised collection of Leonardo da Vinci’s writings and drawings, just like this:

Admin note: The Unofficial Editor is taking a break after scrambling their notes. We hope he’ll be back over-easy. Please click here to read this post online and ensure you see all corrections made after publishing.

If you’re new to SDC, welcome! If you have time to kill, find older editions of SDC Weekly here, and longer posts in the archive here.

Estimated reading time: ~38 mins

📕 The Rolex Legacy - Book Review

James Dowling, aka Mister Rolex, has spent decades writing about Rolex, and his latest tome shows why he’s become a respected voice on Rolex in the world of horology. The book arrives at an opportune moment, as 2025 marks 120 years since Hans Wilsdorf and Alfred Davis opened their doors. Dowling has structured his narrative around the Rolex timeline, breaking it into twelve chapters that each cover around a decade of development.

What I enjoyed about his approach to this book is how Dowling resists the temptation to turn this into a “greatest-hits parade” of so-called iconic references. Instead, he’s chosen watches that help tell the story of how Rolex evolved. Some watches you’ll recognise instantly, and others will likely surprise you, just as they surprised me. As you go through the book, each watch you encounter serves as a kind of way-point, which shows where the company was heading, and more importantly, why certain decisions mattered at the time they were made. Dowling’s commentary accompanying the images makes reading this book feel like a guided-tour in a Rolex museum.

Intro

The introduction cuts through decades of hagiography with a simple comparison. Dowling likens Hans Wilsdorf to Steve Jobs; both brilliant marketers who understood that invention means nothing without refinement and presentation. Apple transformed the MP3 player market without “inventing” digital music, and this is similar to how Wilsdorf built an empire on the wristwatch without inventing many of the things which later made Rolex stand out in marketing.

This framing runs throughout the book, in that Rolex’s genius lay in taking existing concepts (the self-winding watch, the waterproof case, the chronometer-certified movement) and making them work reliably, repeatedly, and at scale. The 2025 novelties with their lubrication-free escapements represent the culmination of this philosophy. In essence, Rolex pursued radical innovation when the moment demanded it, much like Apple did when it launched the iPhone in 2007.

Wilsdorf’s Origin Story

The opening chapter dives into Hans Wilsdorf’s background, and Dowling avoids the usual sanitised versions you’ll find elsewhere. Wilsdorf grew up in a Catholic stronghold in Bavaria (Germany wouldn’t exist as a unified nation until later), shaped by a rigid Protestant education in Coburg after being orphaned at twelve. His father ran a prosperous hardware business, his mother came from brewery wealth, and yet Hans found himself an outsider in a Catholic town, a bright student in a harsh system, and ultimately an orphan navigating three years of compulsory military service.

These obstacles, which Wilsdorf overcame, forged his character. He mastered English, French and mathematics during those Coburg years, completed his “Einjaehrige” Freiwilliger programme (which let educated young men serve just one year rather than three) before moving to Switzerland, then to London, where he met Alfred Davis and founded Wilsdorf & Davis in 1905.

What Dowling captures really well is Wilsdorf’s obsession with accuracy. More than marketing speak or clever positioning, Wilsdorf believed that precision in watches mattered, and he pursued it relentlessly. When watch branding was virtually unknown and retailers slapped their own names on dials, Wilsdorf saw a gap in the market. He began testing movements from each batch, identifying the rare pieces that kept near-perfect time, and then submitted these to observatories for certification.

Dowling’s approach to telling this story resonated with me, as he selected watches which purposefully demonstrate Wilsdorf’s evolving vision.

Ladies’ Watches

The first order from Aegler was for ladies’ and men’s wristwatches fitted with leather straps. This detail matters more than it might seem, because wristwatches for women had achieved social acceptance earlier than men’s models. They were seen as delicate, decorative accessories rather than serious instruments, and men still carried pocket watches, and saw wristwatches as effeminate or impractical.

Wilsdorf & Davis experienced strong sales immediately with these early models, which ensured regular trips to Bienne with increasingly larger orders. The ladies’ watches helped fund the business while Wilsdorf worked to convince men that wristwatches were practical, reliable instruments rather than fashion accessories. This strategy of using commercial success from ladies’ models to subsidise the development of men’s watches would prove crucial during the early years.

All about Rebberg

The 1912 chapter goes into one of the most consequential decisions in Rolex history, which is Wilsdorf’s exclusive relationship with Aegler. Dowling explains that the turning point for Wilsdorf & Davis came when Wilsdorf decided to source movements exclusively from the firm “Les fils de Jean Aegler, fabrique Rebberg”, which translates as “Sons of Jean Aegler, Rebberg factory.”

This raises an interesting question that Dowling addresses directly - does the phrase “Rebberg factory” relate to the location of the factory in the Rebberg section of Bienne, or was it the factory which made Rebberg watches? We may never know, but what we do know is that at some point after 1906, when Jean Aegler’s two sons assumed running the factory, Wilsdorf travelled to Bienne and placed his large order with Hermann Aegler, who Wilsdorf specifically mentions in the Vade Mecum.

Before long, Wilsdorf was able to place the largest order ever given for wristwatches. In his writings, Hans says that the order “amounted to several hundred thousand Swiss Francs.”

Dowling provides additional context to help readers understand this figure. At the time, Switzerland was primarily an agrarian society with concomitant low wages and a currency valued at around 25 Francs to the Pound, meaning that 100,000 Swiss Francs was a little over £4,000. Wilsdorf states “several hundred thousand” without listing an actual amount, but Dowling quite reasonably points out that it ought to have been 200,000 or more, otherwise he couldn’t use the word “several.”

Assuming the initial order was 500,000 Swiss Francs, that works out to around £20,000 which is a figure that nowadays wouldn’t even buy you an entry-level BMW. So if you think about it, over a century ago, this was a huge sum of money; enough, perhaps, to buy a few full-size steam locomotives.

Wilsdorf & Davis bought movements from Aegler in several sizes, ranging from 7 ligne to 13 ligne1. The Rebberg movement was remarkably successful because it was one of the first industrially produced movements available in several sizes but all with identical plate layouts. Between their first deal and the end of the 1920s, Rolex became Aegler’s largest customer, but Aegler wisely avoided putting all his eggs in one basket and continued to sell movements to other firms.

Aegler advertisements from the time mention Rolex, but also Rebberg and Final as two other brands made by them. In 1912, this fact was acknowledged when the firm’s name was changed once again. Now it was “Les fils de Jean Aegler fabrique de montres, Rebberg, Final & Rolex”, or , “Jean Aegler, manufacturer of Rebberg, Final & Rolex watches.”

This “descended into farce” the following year when the firm’s name was changed once again, when it became simply “Aegler SA”2.

The 1912 Rolex with Rebberg Movement

Dowling illustrates this period with a watch from 1912 that captures Wilsdorf’s emerging design philosophy. The watch features a brass dial with black fired enamel and radium numerals, housed in a sterling silver case measuring 35mm in diameter. The movement is a 13 ligne Rebberg calibre - one of those industrially produced movements that made the whole operation viable.

What makes this watch significant is how it exemplifies the relationship between Rolex (branding) and Aegler (manufacturing). The dial proudly displays the Rolex name, but inside beats a Rebberg movement, to reiterate Dowling’s point that Wilsdorf’s genius lay in refining and marketing.

The watch itself speaks to Wilsdorf’s evolving understanding of wristwatch design. The black enamel dial with radium numerals is about legibility and the oversized Arabic numerals filled with radium for low light visibility, showed that Wilsdorf understood his customers needed to read the time quickly and reliably.

The 35mm case size was the sweet spot for men’s watches of the period; large enough to be legible but considered quite substantial for the era. The subsidiary seconds at 6 o’clock maintains the traditional layout, but the coin-edge bezel and prominent onion crown show that Wilsdorf was thinking carefully about how these watches would actually be used on the wrist.

The sterling silver case material is a nod to the economics at the time; gold was prohibitively expensive for most buyers, and silver offered a step up from base metal while keeping prices reasonable. After all, Wilsdorf was building a business, and this meant understanding not just what people wanted, but what they could afford!

The Zerograph

Jump forward to 1941, and Dowling presents one of the most interesting cases of might-have-beens I have read about in Rolex history. The Zerograph (reference 3346) was Rolex’s first in-house chronograph movement and their first watch with a rotating timing bezel. Dowling describes it as follows:

“The most spectacular dead-end from Rolex; their first in-house chronograph movement and their first watch with a rotating timing bezel, yet it went absolutely nowhere. One of the great “might have been” watches.”

As you can see, the watch itself looks wild; the steel case houses an aged “california” dial (showing mixed Roman and Arabic numerals) but the killer detail is that rotating bezel marked with double red bars at 60. You can turn it in either direction to align the zero position with the minute hand, then track elapsed time against the bezel’s markings up to one hour.

You’re probably wondering how this thing works. Aeqler took their regular 10½ ligne Hunter movement and modified it by adding parts underneath the dial and four or five components on the visible side to transform the basic subsidiary seconds movement into a flyback chronostop. The sweep seconds hand runs as you’d expect until you push the button at 2, which causes it to return to the 12 position where it will remain as long as the button stays pressed. When the button is released, the seconds hand starts moving normally again.

Rolex launched the Zerograph in the midst of World War II. Tiny production quantities during wartime meant that fewer than 25 examples have ever appeared. I liked the Zerograph story for this book review because it highlights something about the book rather well. Instead of just documenting a rare reference, Dowling discusses the context of why this innovation went nowhere, while also showing that Rolex possessed the technical capability and ‘innovative nous’ to build cool chronographs… decades before the Daytona appeared.

Panerai connection

Dowling dedicates space to a Panerai watch in a Rolex book, which seems bizarre until you understand the backstory. As you may or may not already know, for the first couple of decades of their existence, all Panerai watches were made by Rolex.

It turns out, this section of their story came about because Rolex screwed up! In the late 1920s, they launched the Oyster wristwatch alongside an Oyster pocket watch, and while the wristwatch changed everything, the pocket watch actually bombed spectacularly. Even then, Wilsdorf wasn’t about to bin a load of expensive waterproof pocket watches, so he did what any resourceful businessman would do, and improvised.

He stripped off the pocket watch bits, turned the case 90 degrees, fit a new dial with the seconds at 9 o’clock instead of 6, soldered on some wire lugs at 12 and 6, and boom; he had himself a wristwatch. These reworked pieces ended up in the 1934 catalogue as reference 2533.

Meanwhile, over in Florence, the Panerai family was juggling two businesses. One was Orologeria Svizzera, a fancy watch shop near the Duomo. The other was G. Panerai & Figlio, which supplied instruments to the Regia Marina or, Italian Navy. At the time, the navy had a problem as they were pioneering the use of combat divers (frogmen doing offensive operations with “midget submarines”), but coordinating underwater attacks meant the divers needed watches. Pocket watches don’t work so well when you’re swimming, as you might imagine.

Giuseppe Panerai spotted the reference 2533 in Rolex’s 1934 catalogue and had a lightbulb moment. His shop happened to be a Rolex agent, so in October 1935, he ordered one to test. It arrived in 9-carat gold with a proper movement inside - a 16¾” calibre from Montilier with 17 jewels in screwed chatons, a snail-shell micrometer regulator, and a Breguet overcoil hairspring. Quality kit, he thought.

The navy tested it thoroughly, and whatever they put it through, it obviously passed. By December, Panerai was back ordering 15 more, but with further modifications. This time they wanted steel cases and dials they’d supply themselves. The crucial detail appears on an invoice from March 1939, describing them as “Oyster acier spéciales pour scaphandriers” or Oyster steel specially for divers. That’s the smoking gun right there; Rolex was building the first “proper dive watches” in a literal sense.

The dial construction Panerai developed is taken for granted now, but it’s actually a clever invention. They used two brass discs; the bottom one was thick-coated with radium and phosphor paste, and the hour markers and numerals were punched out on the top disc so the luminous material could shine through. You could apply way more lume this way than painting it on conventionally.

Dowling shows a reference 3646 from 1940, and honestly, it looks fantastic. The case is 47mm across - absolutely massive for the era - with a black dial and huge Arabic numerals at 12, 3, 6, and 9. You could release this design tomorrow and people would queue up for it. The wire lugs are still there, and there’s no crown guard yet (that came later).

The radium story gets darker, though. Panerai wanted even more luminosity, so they tried using celluloid for the top disc instead of brass, thinking the light would shine through better. Except radium generates heat as well as light, and the celluloid warped, which jammed up the hands. So almost every early Panerai dial you see today has been replaced. The originals basically self-destructed.

Again, what strikes me about this whole saga is how Dowling presents it. He’s showing that Rolex history involves some commercial disasters, some creative problem-solving, and some collaboration that created something groundbreaking - even if most people credit Panerai for it nowadays. The watches only exist because Wilsdorf refused to waste inventory from a failed pocket watch experiment. It may not be the romantic origin story people like to hear, but it’s honest, and that’s what makes this book worth reading.

Holy Year Jubilee Bubbleback

By 1950, Rolex had cracked automatic watches. The Perpetual movement solved the big problem with earlier self-winding watches, which was that you couldn’t wind them manually. This meant that if your watch stopped, you were stuck; you couldn’t know if it was running, nor could you restart it yourself.

The Perpetual sold decently, but it wasn’t flying off the shelves. The price explains why; at 98 guineas for an 18-carat gold model (about £107, or £4,686 in 2025), it cost about a third more than Rolex’s previous top-end watch. That’s a tough sell when people had been winding their watches by hand for centuries without complaint. Why pay extra to avoid something that takes five seconds?

Rolex then tried pivoting to fashion, and introduced new case designs for the Oyster Perpetual with elongated lugs that curved down, and filled the space between the lugs with decorative hoods in gold or steel. Proper art deco stuff. They called them ‘hooded’ models.

Yet again, the context matters. World War I made wristwatches acceptable for men, and World War II made them standard issue. When only a few people wore wristwatches, they stayed small and discreet. But military use demanded larger, more legible watches. Rolex responded by enlarging the Bubbleback movement to 10½ lignes and fitting it in their new flagship, the Datejust, at 36mm in diameter.

These hooded Bubblebacks (pic below) were unfashionable by 1950, but Dowling reckons they’re some of the most exotic cases Rolex ever made for men’s watches. The Holy Year Jubilee Bubbleback (pic above from the book) was one of the last original-style Bubblebacks, made as a special edition for a Catholic Church event. The 1950 Jubilee marked five years since World War II ended, making it a jubilee of reconciliation and forgiveness.

There’s also reference to the above 3536 in the book, and although there is no large image in the book, you can see from this picture it has this huge curved hood filling the space between the straps. Dowling calls it “the most Bauhaus-inspired Rolex Oyster Perpetual”. These hooded models also bombed commercially because the new fashion at the time favoured larger watches, and these looked dated.

However, as we know too well, scarcity drives collector demand, and by the late 1980s, Japanese collectors were paying nearly US$100,000 for Bubblebacks. At the same time, Paul Newman Daytonas sold for $12,000-$15,000. Then Japan’s bubble economy collapsed, taking the Bubbleback market with it. Today, those valuations have completely reversed.

Dowling mentions he uses this example when people ask about investment watches. I know that as a reader of SDC, I need not tell you this, but the lesson is pretty clear; collector markets are fickle, and yesterday’s six-figure watch might be tomorrow’s footnote.

Final thoughts

Dowling could easily have churned out another coffee-table book packed with auction prices and celebrity endorsements. Instead, he covers some interesting history that takes the reader through the things Rolex actually achieved without gilding the lily. What I particularly value is how self-contained each section is; this makes it easy to read, and when I mentioned it to James, he explained this was intentional:

“My idea behind the book and its format is that you can pick it up and read one short essay about one watch and then either put it down and get on with the rest of your life, or read a decade at a time.”

James Dowling

Each chapter follows the same approach; watches are chosen to illustrate progression, and context is provided to explain why innovations mattered when they appeared. If you really want to understand how Rolex became Rolex, Dowling’s made this accessible without dumbing it down.

It is no surprise that this is the first book on Rolex to be published and promoted by one of the UK’s “big three” publishing groups (Hachette Livre). Non-english speakers will be pleased to hear that this book will is also published in Italian, French and German editions; those three along with the US edition will be released a few weeks after the UK edition.

I would strongly urge you to grab a copy, because at £50, this book represents solid value. And in case you’re wondering about my impartiality as a reviewer; I actually pre-ordered this book with my own money the moment it was available to pre-order, and James later arranged to have the publisher send me a review copy before publication. So make of that what you will, but the truth is that if I didn’t enjoy the book, I’d simply not have bothered saying anything about it at all. 😊

Here’s an old SDC post on the subject which you can read while you wait for the book to be delivered 😊: